explosion in the boiler room.”

Andrew Rosenblum broke into a conversation with his wife to say there had been “a really loud bang,” that he would call right back. When he did, on a cell phone, he said he and colleagues needed air. They had used a computer to smash a window, and his wife heard coughing, gasping for breath. Kenneth van Auken tried to call his wife but got the answering machine. “I love you,” he said. Then again, “I love you very much. I hope I’ll see you later.”

All 658 people at Cantor Fitzgerald would soon be dead. One staffer’s body would be found months later, intact, in his suit and tie, seated upright in the rubble.

From Windows on the World, they used to say, you could see for fifty miles on a clear day. That morning, a very clear one, the seventy-nine greeters, waiters, chefs, and kitchen staff had been busy. Regulars had been at breakfast meetings. In the ballroom, a conference sponsored by the British firm Risk Waters had been about to begin. Guests had been greeted, an audiovisual presentation prepared. Manager Howard Kane, on the phone to his wife, had—inexplicably to her—dropped the receiver at exactly 8:46. She wondered for a moment if her husband had had a heart attack. Then she heard a woman scream, “We’re trapped.” Another man picked up the phone to say there was a fire, that they needed the phone to call 911.

Death came slowly at Windows on the World. The story told by the cell phones showed that customers and staff hurried down a floor, to the 106th, to wait for help. Assistant general manager Christine Olender, who phoned downstairs for advice, was told to phone back in a couple of minutes. To help with the smoke, it was suggested, those trapped should hold wet towels to their faces—difficult, for the water supply had been severed. They got some water from the flower vases, a waiter told his wife.

“The situation is rapidly getting worse,” Olender reported. “What are we going to do for air?” Stuart Lee, vice president of a software company, got off an email to his home office. “A debate is going on,” he wrote, “as to whether we should break a window. Consensus is no for the time being.” Then they did break the glass, and people flocked to the window openings.

Every person still alive on those upper floors, some thirteen hundred feet above the ground, was facing either intense heat or dense smoke rising from below. Some pinned their hopes of survival on the one way out they imagined open to them—the roof.

“Get everybody to the roof,” former firefighter Bernie Heeran had told his son Charles, a trader for Cantor Fitzgerald, when he phoned for advice. “Go up. Don’t try to go down.” A colleague, Martin Wortley, told his brother he hoped to escape by helicopter. People had been taken to safety from the roof in the past. On September 11, two police helicopter pilots arrived over the North Tower within minutes—only to realize that any rescue attempt would be jeopardized by the billowing, impenetrable smoke.

Regulations in force at the Trade Center in 2001, moreover, made it impossible even to reach the roof. The way was blocked by three sets of doors, two that could be opened only by authorized personnel with a swipe card, a third operable at normal times only by remote control by security officers far below. The system did not work on 9/11, for vital wires had been cut when the plane hit the tower. Those hoping to escape knew nothing of this.

Early on, one of the helicopter pilots sent a brief message. “Be advised,” he radioed, “that we do have people confirmed falling out of the building at this time.” In the lobby, a firefighter told filmmaker Naudet simply, “We got jumpers.”

VIEWERS AROUND THE WORLD were by now watching events live on television. At the time, however, few in the United States saw the men and women of the Trade Center as they jumped to certain death. Most American editors ruled the pictures too shocking to be shown.

The jumping had begun almost at once. Alan Reiss, of the Port Authority, would remember seeing people falling from high windows within two minutes. Naudet thought “five, ten minutes” passed before he and those around him heard what sounded like explosions—the sound the bodies made as they struck the ground. “They disintegrated. Right in front of us, outside the lobby windows. There was completely nothing left of them. With each loud boom, every firefighter would shudder.”

In the heat of an inferno, driven by unthinkable pain, jumping may for many have been more reflexive action than choice. For those with time to think, the choice between incineration and a leap into thin air may not have been difficult.

Firefighters had never seen anything on this scale, the sheer number of human beings falling, a man clutching a briefcase, another ripping off his burning shirt as he jumped, a woman holding down her skirt in a last attempt at modesty. Some fell in pairs holding hands, others in groups, three or four at a time. Some appeared to line up to jump, like paratroopers.

At least one jump seemed involuntary. Gazing through a long lens, photographer Richard Smiouskas was watching five or six people huddled together in a narrow window when one figure suddenly fell forward and away. It looked as though he had been shoved.

“As the debris got closer to the ground,” firefighter Kevin McCabe said, “you started seeing arms and legs. You couldn’t believe what you were watching … [then] it was like cannon balls hitting the ground. Boom. I remember one person actually hitting a piece of structural steel over a glass canopy … I remember turning my face away … you’d just hear the pounding … tremendously loud, like taking a bag of concrete and throwing it into a closed courtyard. A loud echo … Boom. Boom …”

To Derek Brogan, McCabe’s companion, it “looked like it was raining bodies.” The bodies spelled danger. “We started to get hit,” said Lieutenant Steve Turilli. “You would get hit by an arm or a leg and it felt like a metal pole was hitting you. It was like a war zone.”

Cascading humanity.

JUST FORTY-NINE MINUTES had passed since the hijacking aboard Flight 11 had begun, seventeen since the great airplane roared over Manhattan to bring mayhem and murder to the North Tower. Now, in the sky high above the carnage, a police helicopter pilot spotted something astounding. “Christ!” he shouted into the microphone. “There’s a

THREE

“WE HAVE

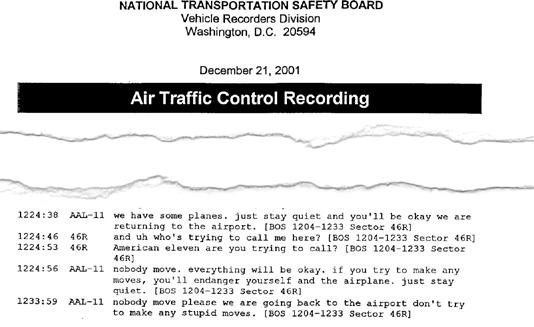

More than three quarters of an hour earlier, as air traffic controller Pete Zalewski tried to get a response from the hijacked Flight 11, he had suddenly heard an unfamiliar voice on the frequency—a man’s voice, with an Arabic accent. Zalewski had trouble making out the words, but moments later a second, clearer transmission persuaded him and colleagues that a hijack was under way. The hijacker, they would conclude, had been trying to address the passengers and—unfamiliar with the equipment—inadvertently transmitted to ground control instead.

A quality assurance specialist then pulled the tape, listened very carefully, and figured out what the Arabic voice had said on the initial, indistinct transmission. “We have some planes. Just stay quiet and you’ll be okay. We are returning to the airport.”

This was a giveaway that—had the U.S. military been able to intervene in time—could have wrecked the operation. The hijackers had seized not two but

AS AMERICA’S FLIGHT 11 had been boarding, United Airlines Flight 175—also departing from Boston—had been readying for takeoff. Copilot Michael Horrocks, a former Marine, called his wife about then, joking that he was flying that day with “some guy with a funny Italian name.” Flight 175’s captain was Victor Saracini, a veteran like Flight 11’s Ogonowski. The team of flight attendants included Kathrryn Laborie and Alfred Marchand—a former police officer—in First Class; Robert Fangman in Business; and Amy King and Michael Tarrou—a couple thinking of getting married—in Coach.

Their fifty-six passengers were the usual mix: a computer expert, a scout for the Los Angeles Kings hockey team, a commercials producer, a senior marketer for a software company, a systems consultant for the Defense Department. There were also foreigners: three Germans, an Israeli, a British man, and an Irish woman—and five young Arabs, three Saudis and two Emiratis. All the Arabs had booked seats in First or Business Class.