18.

19. When the erisis came, the low-paid and hard-worked crew set a matchless example of devotion to duty. The ship’s band, pictured above, played on with ragtime until the water was over their feet; all were lost (

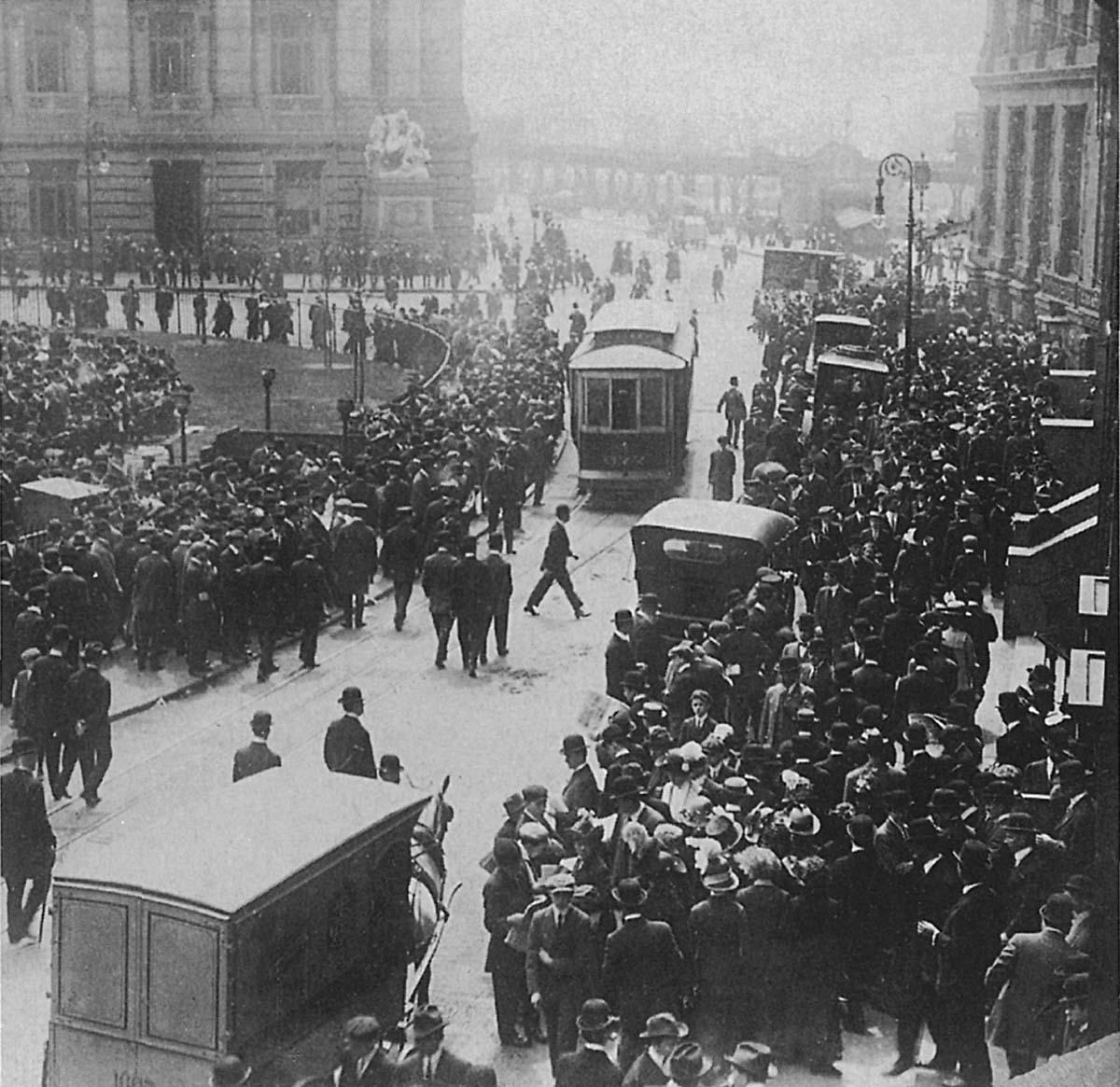

20. All day on 15 April, anxious crowds besieged the White Star offices in New York. They were assured that the

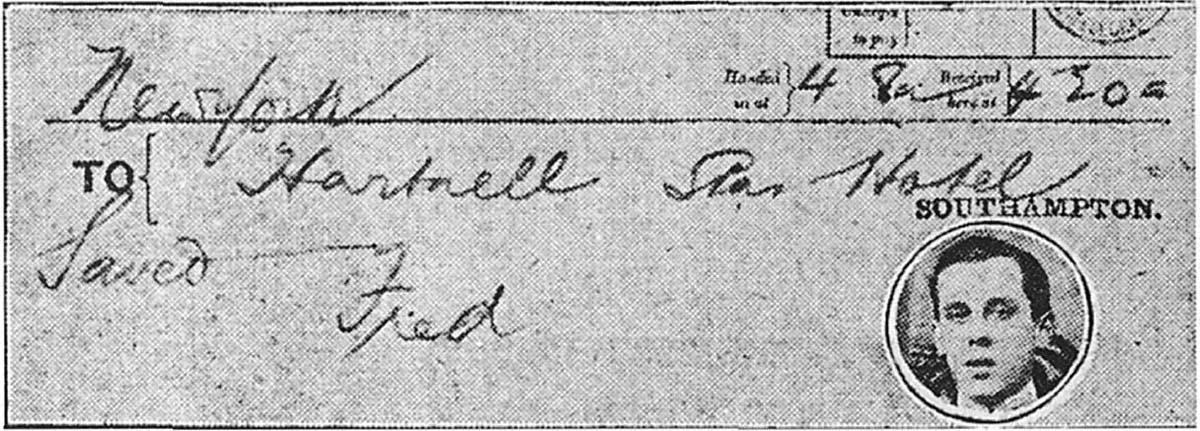

21. A one-word telegram told steward Fred Hartnell’s family all they wanted to know (photo John Webb)

22. Southampton crowds scan the lists of lost and saved posted outside the White Star offices. Many of the crew lived here; in one street twenty families were bereaved (

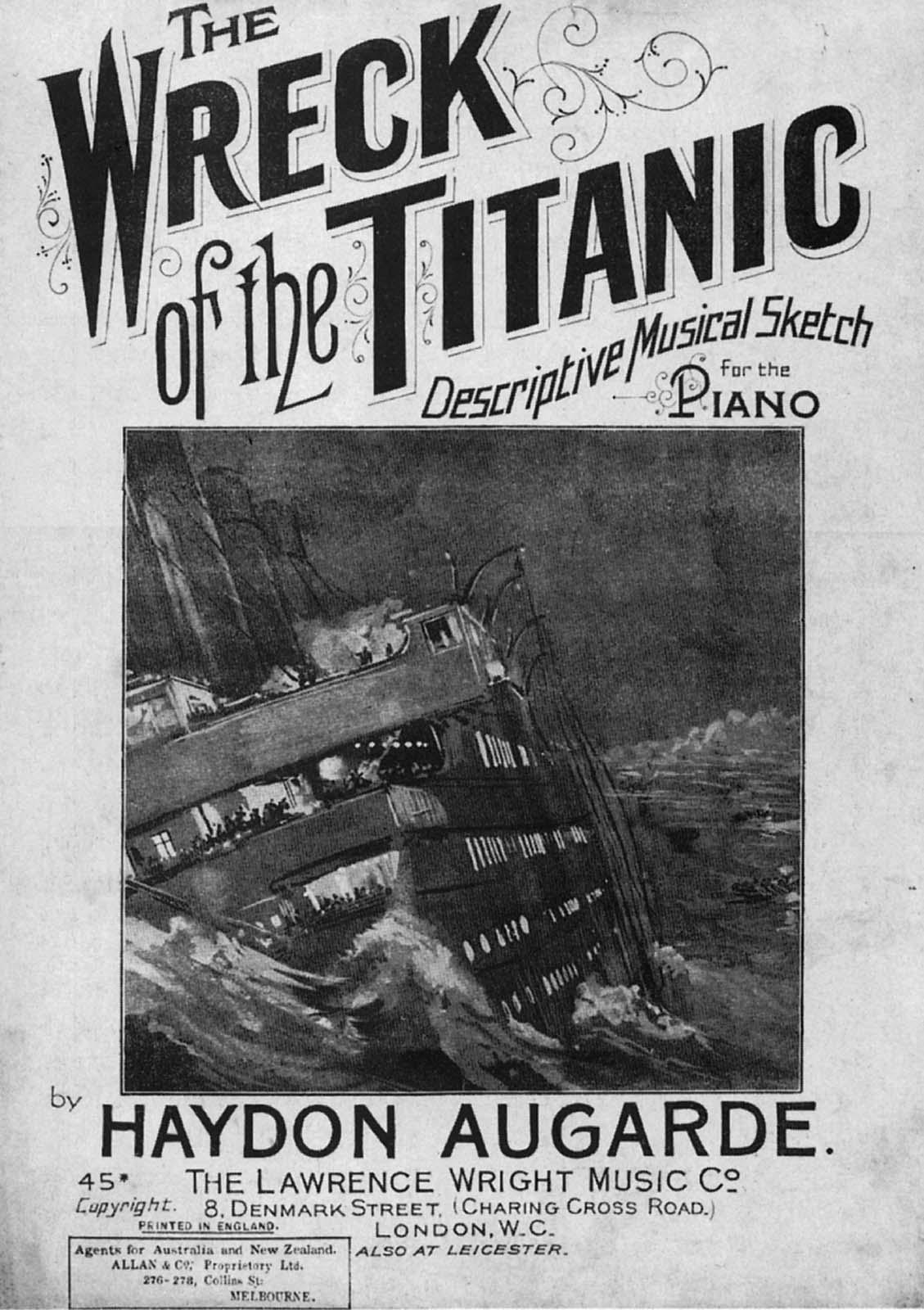

23. Memorial pictures, heavily bordered in black, were eagerly bought from street vendors, as were souvenir napkins, postcards, buttons and bits of pottery. Columns of incredibly poor poetry emerged, and at last eight different pieces of commemorative sheet music appeared on the stands (author)

Acknowledgements

This book is really about the last night of a small town. The

Many of them were there. Some sixty-three survivors were located, and most of these came through handsomely. They are a stimulating mixture of rich and poor, passengers and crew. But all seem to have two qualities in common. First, they look marvellous. It is almost as though, having come through this supreme ordeal, they easily surmounted everything else and are now growing old with calm, tranquil grace. Second, they are wonderfully thoughtful. It seems almost as if, having witnessed man at his most generous, they scorn any trace of selfishness themselves.

Nothing seems to be too much trouble. Many of the survivors have contributed far beyond the scope of the book, just to help me get a better feeling of what it all was like.

For instance, Mrs Noel MacFie (then the Countess of Rothes) tells how—while dining out with friends a year after the disaster—she suddenly experienced the awful feeling of cold and intense horror she always associated with the

Mrs George Darby, then Elizabeth Nye, similarly contributes an appealing extra touch when she tells how— as it grew bitterly cold early Sunday evening—she and some other second-class passengers gathered in the dining room for a hymn-sing, ending with ‘For Those in Peril on the Sea’.

And Mrs Katherine Manning—then Kathy Gilnagh—vividly conveys the carefree spirit of the young people in third class when she talks about the gay party in steerage that same last night. At one point a rat scurried across the room; the boys gave chase; and the girls squealed with excitement. Then the party was on again. Mrs Manning’s lovely eyes still glow as she recalls the bagpipes, the laughter, the fun of being a pretty colleen setting out for America.

Most of the survivors, in fact, give glimpses of shipboard life that have an almost haunting quality. You feel it when Mrs G. J. Mercherle (then Mrs Albert Caldwell) recalls the bustle of departing from Southampton… when Victorine Perkins (then Chandowson) tells of the Ryersons’ sixteen trunks… when Mr Spencer Silverthorne remembers his pleasant dinner with the other buyers on Sunday night… when Marguerite Schwarzenbach (then Frolicher) describes a quieter supper in her parents’ stateroom—she had been sea-sick and this was her first gingerly attempt to eat again.

The crew’s recollections have this haunting quality too. You feel it when fireman George Kemish describes the gruff camaraderie of the boiler rooms… and when masseuse Maud Slocombe tells of her desperate efforts to get the Turkish bath in apple-pie order. Apparently there was a half-eaten sandwich or empty beer bottle in every nook and corner. ‘The builders were Belfast men,’ she explains cheerfully.

The atmosphere conveyed by these people somehow contributes as much as the facts and incidents they describe. I appreciate their help enormously.

Other survivors deserve all my thanks for the way they painstakingly reconstructed their thoughts and feelings as the ship was going down. Jack Ryerson searched his mind to recall how he felt as he stood to one side, while his father argued to get him into boat 4. Did he realize his life was hanging in the balance? No, he didn’t think very much about it. He was an authentic thirteen-year-old boy.

Washington Dodge Jr’s chief impression was the earsplitting roar of steam escaping from the

Third-class passengers Anna Kincaid (then Sjoblom), Celiney Decker (then Yasbeck) and Gus Cohen have also contributed far more than interesting narratives. They have been especially helpful in recreating the atmosphere that prevailed in steerage—a long-neglected side of the story.

The crew too have provided much more than accounts of their experiences. The deep feeling in baker Charles Burgess’s voice, whenever he discusses the

To these and many other

The relatives of people on the

Dear –:

I have before me information stating that you attempted to force your way into one of the lifeboats… and that when ordered back by Major Butt, you slipped from the crowd, disappeared, and after a few moments were seen coming from your stateroom dressed in women’s clothing which was recognized as garments worn by your wife en route. I can’t understand how you can hold your head up and call yourself a man among men, knowing that every breath you draw is a lie. If your conscience continues to bother you after reading this, you had better come forward. There is no truer saying than the old one, ‘Confession is good for the soul.’

Yours truly,—

Besides making letters available, many of the relatives have supplied fascinating information themselves. Especially, I want to thank Captain Smith’s daughter, Mrs M. R. Cooke, for the charming recollection of her gallant father… Mrs Sylvia Lightoller for her kindness in writing to me about her late husband, Commander Charles Lightoller, who distinguished himself in 1940 by taking his own boat over to Dunkirk… Mrs Alfred Hess for making available the family papers of Mr and Mrs Isidor Straus… Mrs Cynthia Fletcher for a copy of the letter written by her father, Hugh Woolner, on board the