For those who are accustomed to thinking about weapons systems or to hearing about horrific wars and massacres around the world, nonviolent action at first glance may seem woefully inadequate. Actually, though, it can be an incredibly powerful technique. The key to nonviolent action is promoting refusal to consent. Even the most powerful weapons system requires human decisions to build, maintain and operate it. If manufacturers, commanders or operators refuse to cooperate, weapons will not be created or used. There are many examples where this process has occurred.

Most studies of nonviolent action have focussed on social and psychological factors, such as how to mobilise support. This is appropriate, since social and psychological factors are the keys to successful nonviolent struggle. Nevertheless, there is a role for technology appropriate for nonviolent defence. That is the theme of this book.

Consider the vast resources, both human and material, that have been devoted to military purposes for many decades. This includes development of weapons systems, training of large armies, military exercises, military industries, and orientation of social institutions to military ends. By comparison, only a tiny effort has been made to improve methods of nonviolent struggle. Is it any wonder that nonviolent defence is not a well-developed alternative? Its occasional successes are all the more remarkable, considering that they are analogous to the success of an army that had no weapons production, no training, no money and no planning. The implication of this comparison is that nonviolent defence should not be dismissed until it has been investigated, supported and tested on a scale similar to military defence.

In the next chapter, the connections between technology and the military are analysed. Chapter 3 gives a brief introduction to the dynamics of nonviolent action. Chapter 4 introduces the main subject: how technology might be used to support nonviolent struggle.

Nonviolent struggle potentially can involve nearly any area one can imagine, from sculpture to soccer. Since technology is increasingly pervasive, this means that design and choice of technology for nonviolent struggle also potentially affects nearly any conceivable area. In many areas, it seems, no one has even begun to think through the implications. Chapters 5 to 8 give special attention to the key areas of communication, survival, the built environment and countering attack. Other areas that might be examined include art, sport, policing, prisons, money and jobs.[8] Chapter 9 discusses the implications of nonviolent action for methods of doing research. Chapter 10 addresses the issue of “policy”: how to move from present-day militarised technology to a technology useful for nonviolent struggle.

The approach I take is to start with nonviolent struggle and see what implications it has for technology. Of course this is not the only way to approach these issues. Another is to start with a vision of a desired society — for example, based on participation, self-reliance, equity and ecological sustainability, as well as nonviolence — and then see what technology is most appropriate to create and sustain it.[9] But in practice these two approaches are not greatly divergent, since in most cases the sort of technology suitable for nonviolent struggle is also suitable for fostering participation, self-reliance and so forth, though in a few particular areas there may be incompatibilities. I find it useful for the purpose of clarity to focus on technology for nonviolent struggle, while noting at various points the potential role of the same technology for promoting other values.

2. MILITARISED TECHNOLOGY

In order to understand the potential role of technology for nonviolent struggle, it is useful to understand the actual role of technology for military purposes. What is technology?[1] A simple and narrow definition is that technology is any physical object created or shaped by humans (or other animals). Technologies include paper, toothbrushes, clothes, violins, hammers, buildings, cars, factories, and genetically modified organisms. These objects can be called artefacts. A broader definition of technology includes both artefacts and their social context, such as the processes, methods and organisations to produce and use them. This includes things such as the manufacturing division of labour, just-in-time production systems, town planning and methods used in scientific laboratories. This broader definition is useful for emphasising that artefacts only have meaning within the context of their creation and use. In this book, the word “technology” refers to both artefacts and their social context.

Similarly, “science” can be defined as both knowledge of the world and the social processes used to achieve it, including discussions in laboratories, science education, scientific journals and funding. The distinction between science and technology, once commonly made, is increasingly blurred. The scientific enterprise is deeply technological, relying heavily on instruments and associated activities. Just as importantly, the production of artefacts requires, in many cases, sophisticated scientific understanding. This is nowhere better illustrated than in contemporary military science and technology. For example, the development of nuclear weapons depended on a deep understanding of nuclear processes, and in turn nuclear technologies provided means for developing nuclear science. For convenience, I often refer just to “technology” rather than “science and technology,” with the understanding that they are closely interlinked and that each can stand in for the other.

In this chapter, I examine military influences on technology. Some influences are immediate and obvious, such as military contracts to produce bazookas and cruise missiles; others are deep and structural, such as military links with capitalism and patriarchy. My approach is to start with the immediate influences and later discuss the deep ones. The first section deals with military funding and applications, training and employment, belief systems and suppression of challenges. The second section deals with “countervailing influences,” namely factors that resist military influence on technology: civilian applications, bureaucratic interests and popular resistance. The final section discusses connections between the military and social structures of the state, capitalism, bureaucracy and patriarchy, and how they can affect technology.

Military Shaping of Technology

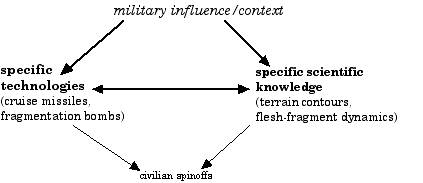

Military priorities play a major role in the development of many technologies.[2] Figures 1 and 2 illustrate how this process, which can be called the military shaping of technology, can occur. Factors such as funding and employment are pictured as influences from the top (“military influence/context”). Military applications are shown in the middle and civilian applications at the bottom. Figure 1 shows the case of science and technology that are very specifically oriented for military purposes, such as the computer software in a cruise missile; there are only occasionally a few civilian spinoffs. Figure 2 shows a more general perspective, looking at entire fields of science and technology. In this case, civilian applications are a significant competing influence.

With figure 1, the military-specific orientation is blatant. With figure 2, it is clear that both military and civilian purposes may be served by the same general fields. I now look in more detail at the specific areas of military funding and applications, training and employment, belief systems and suppression of challenges.

When money and other resources are provided to develop certain technologies, obviously this is an