American flight to New York. And he had never killed anyone again.

When they arrived in New York and an old army friend of his met them at the airport and he introduced her as his wife, she did not disagree. Theirs became a kind of benevolent collaboration, a conspirational friendship. With few others to turn to, it became love. Yes, love. But not the kind of love her daughter or girls like her stumbled into or might expect one day. It was a more strained kind of attachment, yet she could no longer imagine her life without it.

In the early years, there had been more silence than words between them. But when their daughter was born, they were forced to talk to and about her. And when their daughter began to talk back, it made things all that much easier. She was like an orator at a pantomime. She was their Ka, their good angel.

After her daughter was born, she and her husband would talk about her brother. But only briefly. He referring to his “last prisoner,” the one that scarred his face, and she to “my stepbrother, the famous preacher,” neither of them venturing beyond these coded utterances, dreading the day when someone other than themselves would more fully convene the two halves of this same person.

He endorsed the public story, the one that the preacher had killed himself. And she accepted that he had only arrested him and turned him over to someone else. Neither believing the other nor themselves. But never delving too far back in time, beyond the night they met. She never saw any of the articles that were eventually written about her brother’s death. She was too busy concentrating on and revising who she was now, or who she wanted to become.

In the middle of all this incoherent muttering, she realized that her daughter had hung up the phone. Or maybe the phone had come out of the wall while she was pacing back and forth across the kitchen floor. There was now a strange mechanical voice on the line telling her to “hang up and try again.”

She wished she had someone with her now, to get her past the silence that would follow the trying again. She was no longer used to this particular type of loneliness, this feeling that you could be alive or dead and no one would know. She had hoped to close the call by saying something tender and affectionate to her daughter, something like, “You are mine and I love you.” Or maybe she would reach for a now useless cliche, one that she had been reciting to herself all these years, that atonement, reparation, was possible and available for everyone. Or maybe she would think of some unrelated anecdote, a parable, another miracle story, or even some pleasantry, a joke. Anything to keep them both talking. But her daughter was already gone, lost, accidentally or purposely, in the hum of the dial tone.

There was no way to escape this dread anymore, this pendulum between regret and forgiveness, this fright that the most important relationships of her life were always on the verge of being severed or lost, that the people closest to her were always disappearing. The spirits had long since stopped coming through her body via her mysterious spells, which she now knew had a longish name with a series of nearly redundant syllables. These spirits, they’d left her for good the morning that the news was broadcast on the radio that her brother had set his body on fire in the prison yard at dawn, leaving behind no corpse to bury, no trace of himself at all.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

For my father, who, thank goodness, is not in this book. And for my cousin Hans Adonis, who is the book’s parenn, because of all the Duvalier-era research he so lovingly bombarded me with.

Thank you, Laura Hruska, Charles Rowell, Jacqueline Johnson, Brad Morrow, Deborah Treisman, Alice Quinn, Leslie Casimir, Nicole Aragi, and Robin Desser for midwifing and support.

In “The Dew Breaker,” the line “Impossible to deepen that night” is from Graham Greene’s novel about Haiti,

And in one great big breath, welcome to our brood, Zora dear, we love you so much. Manman Nick, Tonton Moise, you’re greatly missed. We row on without you, but I know we’ll meet again.

And finally-

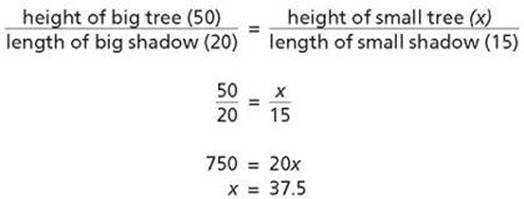

Question:

Two trees, 10 feet apart. Taller tree, 50 feet tall, casts a 20-foot shadow. Shorter tree casts a 15-foot shadow. The sun’s shining on each tree from the same angle. How tall is the shorter tree?

Answer:

The shorter tree (x) is 37.5 feet tall.

Questions courtesy of

Edwidge Danticat

Edwidge Danticat was born in Haiti and moved to the United States when she was twelve. She is the author of several books, including