It was strange to see the wildcount’s riding clothes spotted with oil, his hair tangled by propeller wash. In fact, Alek hadn’t seen Volger since the battle. They’d both been working on the engines every waking moment since Alek’s release.

“Ah, Your Highness,” the wildcount said, offering a halfhearted bow. “I was wondering if you’d been summoned too.”

“I go where the lizards tell me.”

Volger didn’t smile, just turned and started down the stairs. “Beastly creatures. The captain must have important news, to let us see the bridge at last.”

“Perhaps he wants to thank us.”

“I suspect it’s something less agreeable,” Volger said. “Something he didn’t want us to know until

Alek frowned. As usual the wildcount was making sense, if only in a suspicious way. Living among the godless creatures of the

“You don’t trust the Darwinists much, do you?” Alek said.

“Nor should you.” Volger came to a halt, looking up and down the corridors. He waited until a pair of crewmen had passed, then pulled Alek farther down the stairway. A moment later they were on the lowest deck of the gondola, in a dark corridor lit only by the ship’s glowworms.

“The ship’s storerooms are almost empty,” Volger said quietly. “They don’t even guard them anymore.”

Alek smiled. “You’ve been sneaking about, haven’t you?”

“When I’m not adjusting gears like a common mechanik. But we must speak quickly. They’ve caught me here once already.”

“So, what did you think of my message?” Alek asked. “Those ironclads are headed for Constantinople, aren’t they?”

“You told them who you were,” Count Volger said.

Alek froze for a moment as the words sank in. Then he blinked and turned away, his eyes stinging with shame and frustration. It felt like being a boy again, when Volger had landed hits with his saber at will.

He cleared his throat, reminding himself that the wildcount was no longer his tutor. “Dr. Barlow told you, didn’t she? To show that she has something over us.”

“Not a bad guess. But it was simpler than that—Dylan let it slip.”

“Dylan?” Alek shook his head.

“He didn’t realize you kept secrets from me.”

“I don’t keep any …,” Alek began, but it was pointless arguing.

“Have you gone mad?” Volger whispered. “You’re the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. Why would you

“Dylan and Dr. Barlow aren’t enemies,” Alek said firmly, looking Count Volger full in the eye. “And they don’t know I’m the legal heir to the throne. Nobody knows about the pope’s letter but you and me.”

“Well, thank heaven for that.”

“And I

“No. You should have never admitted anything, whatever they’d guessed! That boy Dylan is completely guileless—incapable of keeping a secret. You may think he’s your friend, but he’s just a peasant. And you’ve put your future in his hands!”

Alek shook his head. Dylan might be a commoner, but he

“Think for a moment, Volger. Dylan let it slip to

The man stepped closer in the darkness, his voice hardly above a whisper. “I hope you’re right, Alek. Otherwise the captain is about to tell us that his new engines will be taking us back to Britain, where they’ll have a cage waiting for you. Do you think being the Darwinists’ pet monarch will be agreeable?”

Alek didn’t answer for a moment, replaying all of Dylan’s earnest promises in his mind. Then he turned away and started up the stairs.

“He hasn’t betrayed us. You’ll see.”

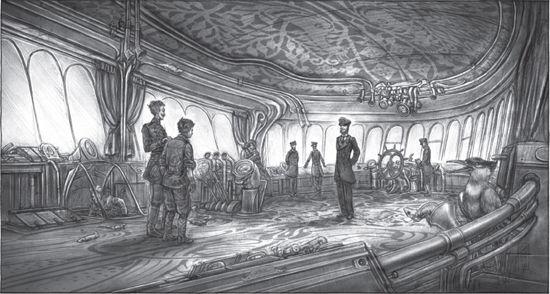

The bridge was much larger than Alek had imagined.

It took up the entire width of the gondola, curving with the gentle half circle of the airship’s prow. The afternoon sun streamed through windows that stretched almost to the ceiling. Alek stepped closer to one—the glass leaned gently outward, allowing him to peer straight down at the dazzling water slipping past.

Reflected in the window, a dozen message lizard tubes coiled along the ceiling; others sprouted from the floor like shiny brass mushrooms. Levers and control panels lined the walls, and carrier birds fluttered in the cages hanging in one corner. Alek closed his eyes for a moment, listening to the buzz and chatter of men and animals.

Volger gently pulled his arm. “We’re here to parley, not to gawk.”

Setting a serious expression on his face, Alek followed Volger. But still he watched and listened to everything around him. No matter what the captain’s news turned out to be, he wanted to soak in every detail of this place.

At the front of the bridge was the master wheel, like an old sailing ship’s, carved in the Darwinists’ sinuous style. Captain Hobbes turned from it to greet them, a smile on his face.

“Ah, gentlemen. Thank you for coming.”

Alek followed Volger’s lead and offered the captain a shallow bow, one suited for a minor nobleman of uncertain importance.

“To what do we owe the pleasure?” Volger asked.

“We’re under way again,” Captain Hobbes said. “I wanted to thank you personally for that.”

“We’re glad to help,” Alek said, hoping that for once Count Volger’s suspicions had proven overblown.

“But I also have bad news,” the captain continued. “I’ve just received word that Britain and Austria-Hungary are officially at war.” He cleared his throat. “Most regrettable.”

Alek drew in a slow breath, wondering how long the captain had known. Had he waited until the engines were fixed to tell them? Then Alek realized that he and Volger were smeared with grease, dressed like tradesmen, while Captain Hobbes preened in his crisp blue uniform. Suddenly he hated the man.

“This changes nothing,” Volger said. “We’re not soldiers, after all.”

“Really?” The captain frowned. “But judging by their uniforms, your men are members of the Hapsburg Guard, are they not?”

“Not since we left Austria,” Alek said. “As I told you, we had to flee for political reasons.”

The captain shrugged. “Deserters are still soldiers.”

Alek bridled. “My men are hardly—”

“Are you saying we’re prisoners of war?” Volger interrupted. “If so, we shall collect our men from the engine pods and retire to the brig.”

“Don’t be hasty, gentlemen.” Captain Hobbes raised his hands. “I merely wanted to give you the bad news, and to beg your indulgence. This puts me in an awkward situation, you must understand.”

“We find it …

“Of course,” the captain said, ignoring Alek’s tone. “I would prefer to reach some arrangement. But try to understand my position. You’ve never told me exactly who you are. Now that our countries are at war, that makes your status rather complicated.”

The man waited expectantly, and Alek looked at Volger.

“I suppose it does,” the wildcount said. “But we still prefer not to identify ourselves.”

Captain Hobbes sighed. “Then I shall have to turn to the Admiralty for orders.”

“Do let us know what they say,” Count Volger said simply.

“Of course.” The captain touched his hat and turned back to the wheel. “Good day, gentlemen.”

While Volger bowed again, Alek turned stiffly about and walked away, still angry at the man’s impertinence. But as he headed back toward the hatchway, he found himself slowing a little, just to listen for a few more seconds