house he’d been born in, last surviving structure of an old mill town. The present-day town of Munro’s Furnace, such as remained, lay another three-quarters of a mile down the road.

As the car crunched to a halt on gravel, she stared unblinking. No matter how long she lived here, it always proved something of a shock, this reality. Funny, but in her mind she always pictured the place the way it had been when they’d first begun fixing it up—scaffolding and ladders, cans of paint and bags of cement everywhere. A royal mess, but she hadn’t cared because they’d been happy, working together until…

Glaring headlights held the cobbled-together structure in cruel scrutiny: clapboard walls beneath phantom paint; boarded first-floor windows she couldn’t afford to repair; collapsing front porch propped up with old bed slats and cinder blocks. She switched off the engine, got out, and night fell on her.

Her grandmother’s home in Queens—no matter how miserable she’d been there as a child—had at least held life. This house lay black and silent. Looking up, she strained to make out the blind diamond panes of her son’s bedroom window.

While she limped around to the back, shoulders straight, she forced herself to walk closer to the bristling shadows, farther from the house than necessary. She mounted the wobbling steps to the porch and stood, fumbling her key into the kitchen door. Why couldn’t Pamela ever remember to switch on the porch light before she left? Something wet and warm pressed against the back of her hand, and she jumped. “Stupid dog!”

From the darkness of the porch came a yawning whine and the scratching of claws on wood. “Get away, Dooley.” When she got the door open, the moldy smell of the house met her like an invisible wall. “Go back to sleep. You can’t come in.” She heard the dog yawn again and flop back down on the porch with a deflating sigh.

Pulling the door closed behind her, she could see nothing, and she stumbled across the rough wooden floor, feeling along the wall for the switch. She flinched when yellowish light flooded the kitchen.

A three-inch millipede tapped along the stove, waving its antennae in blinded confusion. Darkness bulged at the door. Pamela’s note lay on the crumb-littered tablecloth.

The house returned to absolute darkness as she switched off the kitchen light, and a cricket began to throb beneath a floorboard. Groping her way into the living room, she walked into a chair and cursed, then felt her way toward the stairs. The other rooms on the first floor had been closed off. From outside, the voices of the night—the insects and the whispering trees—sounded low and indistinct.

As she started up the stairs, her hand rode along the smooth banister, smearing the dust. She turned left at the landing. Boards creaked under her footsteps along the hall—a loud thump followed by the weaker, softer sound. She went straight to her room.

Without turning on a light, she put the scanner on the dresser, then pulled bobby pins and elastic bands out of her hair. A hair band knotted, and she yanked it out, tossed it on the dresser. Feeling sweaty and dirty, but too tired to do anything about it, she fell across the too-soft, untidy bed. Mounds of laundry lay heaped around her, and her leg ached.

From the scanner, police calls muttered distantly. She listened to them drone and thought about getting undressed, knowing her reflexes would alert her if the tone that preceded ambulance calls sounded. The scanner’s small red light was somehow comforting, and her mind drifted to the night-light Granny Lee had given her so long ago. Even as a child, she’d thought it cowardly and every night had dragged herself out of bed to unplug it, loathing herself all the while.

Something rattled overhead. It could have been another tile that had worked loose, clattering across the roof…or it might have come from the attic. She listened to the house, to the beams that groaned like an old wooden ship.

She seldom truly slept anymore. Habitually, she’d push herself to exhaustion, then lie twitching on the edge of wakefulness, only to be active at dawn. The hours stretched long before her. Lying in the dark, eyes open, she always ran out of the distractions and evasions.

But her work on the ambulance was important. She tried to hold to that thought as the redness of the scanner grew hazy. Her scalp still smarted from the hair band, and her thoughts drifted to how Aunt Jeanie, jealous of her light skin, had always teased her about her kinky hair, and how Granny Lee had always tried to straighten it with chemicals that stank and burned.

She closed her eyes, and the darkness was complete.

The bedroom window was open but with the shade drawn against the night. Ten yards from the house, beyond the waving grasses, pines swayed, making a noise like the sea, like a still-boiling primeval element.

And the dream began.

Always, it was the same: torturous fragments raced through her mind, baffling glimpses of frenzy, the savage joy of forest revels, the crazed pursuit of those that fled, blood gushing hot, the rending of fawn’s flesh and the splattering of trees in infantile desecration, mad decoration, alone and not alone. She writhed on the bed.

A different noise filtered into her nightmare—a rhythmic groaning, full of the creak of bedsprings.

Half awake, she got up and made her way along the hall. At its end, steep narrow stairs were set in a closet like alcove, and she went up them practically on all fours, feeling her way in the dark.

The attic room had a sour, baby smell. She felt in the air for the string, and the naked, insect-encrusted bulb blazed, dancing. The attic was a mad jumble of chairs, boxes, broken and unwanted objects from all over the house.

The cot shook, creaking with the boy’s efforts. Naked and sweaty, his ten-year-old body twisted into serpentine knots on the bedding, and his teeth locked in the rumpled pillow he ripped with convulsive jerks of his head. The boy was asleep.

She stared. His hair was curly like hers, coppery like his father’s, and in the leprous bulb light, his damp skin had an unwholesome yellow sheen. He was the source of the sour smell. She wanted to turn away, obliquely wondering what wordless images comprised his dreams.

He growled.

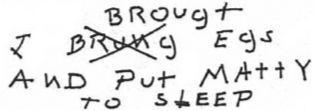

“Matthew.”

She simply spoke his name, and though his body remained tensed, all movement ceased.

Her son. For perhaps the thousandth time, she wondered about herself, about why she felt no tenderness when she gazed on this child. She would not pretend to herself. Her mind slid to her late husband: she’d let Wallace down in so many ways. The house. The boy.

There were long scratches on the boy’s legs.

He’d been in the woods again, she thought uneasily.

She stared another moment. The sheet was a graying tangle, tucked between his legs, and she thought he might have wet the bed again.

As on so many other nights, she groped her way back down into the narrow darkness.