ferry; he made the false statements about the trip to Hokkaido, and he arranged for the use of assumed names on the different planes. Because of his position, he travels easily and often and it is simple for him to take along an assistant who will do as he is told.

Later, when he learned that Sayama and his woman companion had committed suicide by taking cyanide, he took fright. He was certain Yasuda had done it. From that moment, I believe Yasuda started to threaten, to put pressure on him. Ishida now found himself at the mercy of this man. I am sure it was at Yasuda's suggestion that he sent Sasaki, a member of his staff, to the Metropolitan Police Board to give evidence on the train trip in Hokkaido. Of course, this turned out to be Yasuda's undoing.

Yasuda had lost interest in Otoki and used her as an instrument in the murder of Sayama. The motive for Ryoko's participation was probably more than just a desire to help her husband. She could have wanted to kill Otoki, even though she accepted her as her husband's mistress. This had not changed her feelings as a woman and wife. Because Ryoko, a wife in name only, deep in her heart was probably more than normally jealous. The white fire of jealousy was burning within her like phosphorous, waiting for an opportunity to burst into flames. Otoki is the real victim of the drama. Yasuda himself may not have known whether his real purpose was to kill Sayama in order to put Ishida in his debt, or to get rid of Otoki who had become a burden to him.

All that I have written to you is my own analysis of the case- aided by the letter the Yasudas left.

Yes, Tatsuo Yasuda and his wife Ryoko were found dead in their house in Kamakura when we arrived to arrest them. They had taken cyanide. This time there was no attempt at mystification. Tatsuo Yasuda knew we were on his trail. He took his own life, followed by his wife whose physical condition had become critical. Yasuda left no message; it was Ryoko who wrote the letter. In it she admits the crime. Frankly, I am skeptical. I find it hard to accept that a man as tough as Yasuda would commit suicide. I believe that Ryoko, who knew her end was near, could have planned it and taken her husband with her. She was that kind of a woman.

I must admit I was relieved to find the Yasudas dead, because there is almost no material evidence in this murder case. It is all circumstantial. I am even surprised we were able to secure a warrant for their arrest. It was the type of case which, if brought to trial, one could not be sure of the outcome.

Speaking of the lack of evidence, this applies also to Division Chief Ishida. He was transferred to another division and, believe it or not, was given a promotion. This may appear incredible to you, but such things happen. He will probably become a bureau chief or a vice-minister, and may even run for a seat in the Diet. I feel sorry for these poor subordinates of his whom he uses as stepping stones. However, even if they know they are being abused, they will try to stay in his good graces by showing their loyalty. Their desire for advancement is pathetic. Which reminds me: Kitaro Sasaki, the man who made the trip to Hokkaido with Ishida and who was of help to Yasuda, was made section chief. Here again, there is nothing we can do. The Yasudas are dead.

The whole case has left a bad taste in my mouth. Sitting here at home, completely relaxed, a glass of cold beer at my elbow, I don't have the satisfaction I generally feel when a case is solved and the criminal has been turned over to the Public Prosecutor. This is a very long letter; I trust you were not bored. I expect to take my vacation this autumn and, at your kind suggestion, my wife and I will visit you in Kyushu.

With best wishes,

Kiichi Mihara

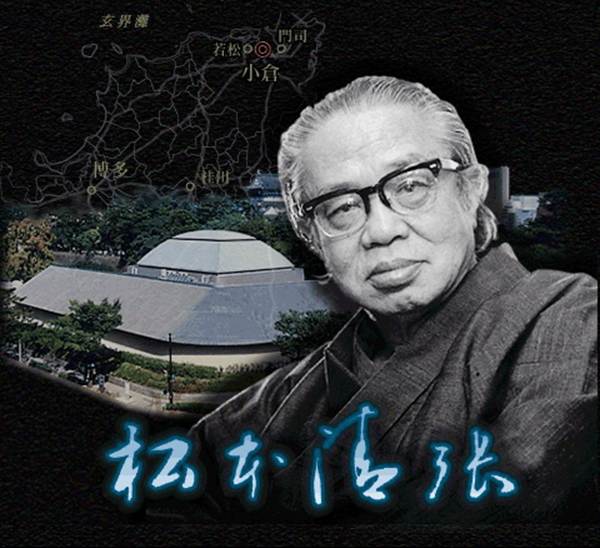

Seicho Matsumoto

Seicho Matsumoto was born in 1909 in Fukuoka Prefecture, Kyushu. Now Japan's foremost master of mystery, Matsumoto was forty years old before he launched his literary career. His first work appeared in the influential