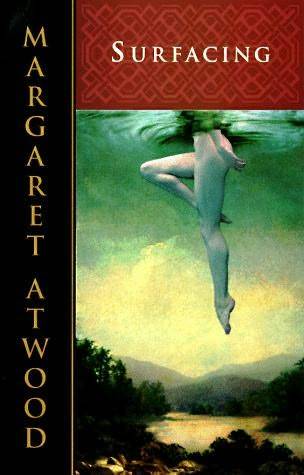

Margaret Atwood

Surfacing

First Published in 1972

One

Chapter One

I can't believe I'm on this road again, twisting along past the lake where the white birches are dying, the disease is spreading up from the south, and I notice they now have sea-planes for hire. But this is still near the city limits; we didn't go through, it's swelled enough to have a bypass, that's success.

I never thought of it as a city but as the last or first outpost depending on which way we were going, an accumulation of sheds and boxes and one main street with a movie theatre, the itz, the oyal, red R burnt out, and two restaurants which served identical grey hamburger steaks plastered with mud gravy and canned peas, watery and pallid as fisheyes, and french fries bleary with lard. Order a poached egg, my mother said, you can tell if it's fresh by the edges.

In one of those restaurants before I was born my brother got under the table and slid his hands up and down the waitress's legs while she was bringing the food; it was during the war and she had on shiny orange rayon stockings, he'd never seen them before, my mother didn't wear them. A different year there we ran through the snow across the sidewalk in our bare feet because we had no shoes, they'd worn out during the summer. In the car that time we sat with our feet wrapped in blankets, pretending we were wounded. My brother said the Germans shot our feet off.

Now though I'm in another car, David's and Anna's; it's sharp-finned and striped with chrome, a lumbering monster left over from ten years ago, he has to reach under the instrument panel to turn on the lights. David says they can't afford a newer one, which probably isn't true. He's a good driver, I realize that, I keep my outside hand on the door in spite of it. To brace myself and so I can get out quickly if I have to. I've driven in the same car with them before but on this road it doesn't seem right, either the three of them are in the wrong place or I am.

I'm in the back seat with the packsacks; this one, Joe, is sitting beside me chewing gum and holding my hand, they both pass the time. I examine the hand: the palm is broad, the short fingers tighten and relax, fiddling with my gold ring, turning it, it's a reflex of his. He has peasant hands, I have peasant feet, Anna told us that. Everyone now can do a little magic, she reads hands at parties, she says it's a substitute for conversation. When she did mine she said 'Do you have a twin?' I said No. 'Are you positive,' she said, 'because some of your lines are double.' Her index finger traced me: 'You had a good childhood but then there's this funny break.' She puckered her forehead and I said I just wanted to know how long I was going to live, she could skip the rest. After that she told us Joe's hands were dependable but not sensitive and I laughed, which was a mistake.

From the side he's like the buffalo on the U.S. nickel, shaggy and blunt-snouted, with small clenched eyes and the defiant but insane look of a species once dominant, now threatened with extinction. That's how he thinks of himself too: deposed, unjustly. Secretly he would like them to set up a kind of park for him, like a bird sanctuary. Beautiful Joe.

He feels me watching him and lets go of my hand. Then he takes his gum out, bundling it in the silver wrapper, and sticks it in the ashtray and crosses his arms. That means I'm not supposed to observe him; I face front.

In the first few hours of driving we moved through flattened cow-sprinkled hills and leaf trees and dead elm skeletons, then into the needle trees and the cuttings dynamited in pink and grey granite and the flimsy tourist cabins, and the signs saying GATEWAY TO THE NORTH, at least four towns claim to be that. The future is in the North, that was a political slogan once; when my father heard it he said there was nothing in the North but the past and not much of that either. Wherever he is now, dead or alive and nobody knows which, he's no longer making epigrams. They have no right to get old. I envy people whose parents died when they were young, that's easier to remember, they stay unchanged. I was sure mine would anyway, I could leave and return much later and everything would be the same. I thought of them as living in some other time, going about their own concerns closed safe behind a wall as translucent as jello, mammoths frozen in a glacier. All I would have to do was come back when I was ready but I kept putting it off, there would be too many explanations.

Now we're passing the turnoff to the pit the Americans hollowed out. From here it looks like an innocent hill, spruce-covered, but the thick power lines running into the forest give it away. I heard they'd left, maybe that was a ruse, they could easily still be living in there, the generals in concrete bunkers and the ordinary soldiers in underground apartment buildings where the lights burn all the time. There's no way of checking because we aren't allowed in. The city invited them to stay, they were good for business, they drank a lot.

'That's where the rockets are,' I say. _Were._ I don't correct it.

David says 'Bloody fascist pig Yanks,' as though he's commenting on the weather.

Anna says nothing. Her head rests on the back of the seat, the ends of her light hair whipping in the draft from the side window that won't close properly. Earlier she was singing, House of the Rising Sun and Lili Marlene, both of them several times, trying to make her voice go throaty and deep; but it came out like a hoarse child's. David turned on the radio, he couldn't get anything, we were between stations. When she was in the middle of St. Louis Blues he began to whistle and she stopped. She's my best friend, my best woman friend; I've known her two months.

I lean forward and say to David, 'The bottle house is around this next curve and to the left,' and he nods and slows the car. I told them about it earlier, I guessed it was the kind of object that would interest them. They're making a movie, Joe is doing the camera work, he's never done it before but David says they're the new Renaissance Men, you teach yourself what you need to learn. It was mostly David's idea, he calls himself the director: they already have the credits worked out. He wants to get shots of things they come across, random samples he calls them, and that will be the name of the movie too: _Random Samples._ When they've used up their supply of film (which was all they could afford; and the camera is rented) they're going to look at what they've collected and rearrange it.

'How can you tell what to put in if you don't already know what it's about?' I asked David when he was describing it. He gave me one of his initiate-to-novice stares. 'If you close your mind in advance like that you wreck it. What you need is flow.' Anna, over by the stove measuring out the coffee, said everyone she knew was making a movie, and David said that was no fucking reason why he shouldn't. She said 'You're right, sorry'; but she laughs about it behind his back, she calls it Random Pimples.

The bottle house is built of pop bottles cemented together with the bottoms facing out, green ones and brown ones in zig-zag patterns like the ones they taught us in school to draw on teepees; there's a wall around it made of bottles too, arranged in letters so the brown ones spell BOTTLE VILLA.

'Neat,' David says, and they get out of the car with the camera. Anna and I climb out after them; we stretch our arms, and Anna has a cigarette. She's wearing a purple tunic and white bellbottoms, they have a smear on them already, grease from the car. I told her she should wear jeans or something but she said she looks fat in them.

'Who made it, Christ, think of the work,' she says, but I don't know anything about it except that it's been there forever, the tangled black spruce swamp around it making it even more unlikely, a preposterous monument to some quirkish person exiled or perhaps a voluntary recluse like my father, choosing this swamp because it was the only place where he could fulfill his lifelong dream of living in a house of bottles. Inside the wall is an attempted lawn and a border with orange mattress-tuft marigolds.

'Great,' says David, 'really neat,' and he puts his arm around Anna and hugs her briefly to show he's pleased, as though she is somehow responsible for the Bottle Villa herself. We get back in the car.

I watch the side windows as though it's a T.V. screen. There's nothing I can remember till we reach the border, marked by the sign that says BIENVENUE on one side and WELCOME on the other. The sign has bullet holes in it, rusting red around the edges. It always did, in the fall the hunters use it for target practice; no matter how many times they replace it or paint it the bullet holes reappear, as though they aren't put there but grow by a kind of inner logic or infection, like mould or boils. Joe wants to film the sign but David says 'Naaa, what for?'

Now we're on my home ground, foreign territory. My throat constricts, as it learned to do when I discovered people could say words that would go into my ears meaning nothing. To be deaf and dumb would be easier. The cards they poke at you when they want a quarter, with the hand alphabet on them. Even so, you would need to learn spelling.

The first smell is the mill, sawdust, there are mounds of it in the yard with the stacked timber slabs. The pulpwood goes elsewhere to the paper mill, but the bigger logs are corralled in a boom on the river, a ring of logs chained together with the free ones nudging each other inside it; they travel to the saws in a clanking overhead chute, that hasn't been changed. The car goes under it and we're curving up into the tiny company town, neatly planned with public flowerbeds and an eighteenth century fountain in the middle, stone dolphins and a cherub with part of the face missing. It looks like an imitation but it may be real.

Anna says 'Oh wow, what a great fountain.'

'The company built the whole thing,' I say, and David says 'Rotten capitalist bastards' and begins to whistle again.

I tell him to turn right and he does. The road ought to be here, but instead there's a battered chequerboard, the way is blocked.

'Now what,' says David.

We didn't bring a map because I knew we wouldn't need one. 'I'll have to ask,' I say, so he backs the car out and we drive along the main street till we come to a corner store, magazines and candy.

'You must mean the old road,' the woman says with only a trace of an accent. 'It's been closed for years, what you need is the new one.' I buy four vanilla cones because you aren't supposed to ask without buying anything. She gouges down into the cardboard barrel with a metal scoop. Before, the ice cream came rolled in pieces of paper which they would peel off like bark, pressing the short logs of ice cream into the cones with their thumbs. Those must be obsolete.

I go back to the car and tell David the directions. Joe says he likes chocolate better.