like many other pieces of business jargon, a development of the 1960s. My pastiche is not unlike the ‘corporate speak generators’ that can be found online, producing strings of humorous nonsense — the humour, of course, lying in the fact that the results are uncomfortably close to the realities of what is daily heard and read in many offices.

What is going on? It isn’t just a matter of jargon. Every profession, trade or social group has its special language — the technical terms, abbreviations and idioms which show that you are an electrician, lawyer, priest, journalist, doctor… To insiders, these terms are unproblematic: they define their professionalism. People only start condemning such language as jargon when the insiders talk to outsiders in an unthinking or pretentious way, using obscure words without considering the effect on their listeners.

Corporate speak is more than jargon. While such terms as synergy, incentivise and leveraging can be difficult to grasp, there’s nothing especially hard about wow factor, low-hanging fruit or (at least to cricket fans) close of play. But these phrases nonetheless attract criticism. The charge is that, even though they are simple, they have lost their meaning through overuse. They have become automatic reactions, verbal tics, a replacement for intelligent thinking. In short, they have become inappropriately used cliches.

These days the charges come from both inside and outside the world of business management. And the criticisms are particularly harsh when other domains pick up corporate speak. Government departments especially have to be careful if they lapse into it. A UK parliamentary select committee in July 2009 examined the matter, and the chairman introduced the topic using another pastiche:

Perhaps I could say, by way of introduction, welcome to our stakeholders. We look forward to our engagement, as we roll out our dialogue on a level playing field, so that, going forward in the public domain, we have a win-win step change that is fit for purpose across the piece.

Everyone in the room recognised the symptoms. And the subsequent discussion focused on the kinds of language routinely being used in government circles, such as unlocking talent, partnership pathways, a quality and outcomes framework and best practice flowing readily to the frontline. What could be done about it?

It’s easier to identify symptoms than to suggest cures. And it’s easy to parody. Eradicating habitual usage is hard. But there is a mood around these days that something has to be done. Whether in business or in government, recognising models of good practice, and rewarding them, will be an important first step.

94. LOL — extspeak (20th century)

94. LOL — extspeak (20th century)

When LOL first appeared on computer and mobile phone screens, it caused not a little confusion. Some people were using it to mean ‘lots of love’. Others interpreted it as ‘laughing out loud’. It was an ambiguity that couldn’t last. Who knows how many budding relationships foundered in the early 2000s because recipients took the abbreviation the wrong way? Today it’s settled down. Almost everyone now uses LOL in its ‘laughing’ sense. And it’s one of the few text-messaging acronyms to have crossed the divide between writing and speech.

Dictionaries of text-messaging list hundreds of acronyms and give the impression that a new language, textese, has emerged. In fact, now that collections of real text messages have been made and studied, it transpires that only a few of those abbreviations are used with any frequency. Replacing see by c, you by u and to by 2 are some of the commonly used strategies. But the kind of message in which every word is an abbreviation (thx 4 ur msg c u 18r) is really rather unusual. On average, only about 10 per cent of the words in a text are abbreviated. And in many adult texting situations, textisms are frowned upon, or even banned, because the organisers know that not everyone will understand them.

The novelty of texting abbreviations has also been overestimated. Several were actually part of computer interaction in chatrooms long before texting arrived in the late 1990s. And some can be traced back over many years. In a poem called ‘An Essay to Miss Catherine Jay’, an anonymous author begins:

An S A now I mean 2 write

2 U sweet K T J…

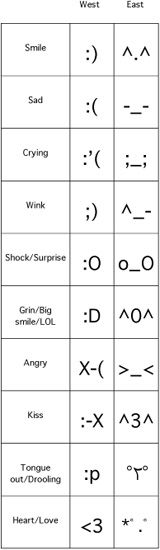

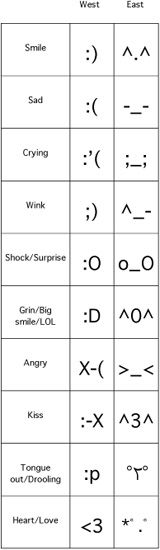

20. An illustration of cultural differences in the use of emoticons. In Western countries, emoticons are viewed sideways and focus on the mouth; in the East, they are horizontal and focus on the eyes.

20. An illustration of cultural differences in the use of emoticons. In Western countries, emoticons are viewed sideways and focus on the mouth; in the East, they are horizontal and focus on the eyes. It was published in 1875. Lewis Carroll and Queen Victoria are among the many Victorians who played with such sound/letter substitutions.

On the other hand, there’s nothing in older usage that quite lives up to the modern penchant for taking an abbreviation and adding to it. Thus, from the basic form imo (‘in my opinion’) we find imho (‘in my humble opinion’), imhbco (‘in my humble but correct opinion’) and imnsho (‘in my not so humble opinion’). And a similar thing happens to the other big innovation of contemporary electronic communication: the emoticon or smiley. Based on :), used to express a friendly reaction, we find :)), :))) and other extensions conveying increased intensity of warmth.

It’s difficult to say how many of the novel computer abbreviations will remain in the language, once the novelty has worn off. Txt, txtng and related forms may survive, but only as long as the technology does. And who can say whether, in fifty years’ time, people will still be typing such forms as brb (‘be right back’) and afaik (‘as far as I know’) and sending each other combinations of cat pictures + non-standard grammar (lolcats)? Will there still be keyboards and keypads then, even, or will everything be done through automatic speech recognition? With electronic communication, as I said earlier (§32), we ain’t seen nothin’ yet.

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century)

95. Jazz — word of the century (20th century)

Since 1990, members of the American Dialect Society have voted on the ‘Word of the Year’ (§91). The selection reflects social as much as linguistic factors. In 1999, they chose Y2K. In 2001, 9–11. And the economic crisis of recent years is reflected in sub-prime for their 2007 choice and bailout for 2008. It’s thus something of a relief to find tweet their selection for 2009 (§100).

Choosing a word for a year is difficult enough. Much more difficult is a ‘Word of the Decade’. In 2010 the members of the Society chose google. That seems fair enough. But what would you do for the ‘Word of the Century’?

They chose jazz. It was perhaps bending the truth a little, but not much. The word doesn’t surface until the century is over ten years old. In 1913, a San Francisco commentator described jazz as ‘a futurist word which has just joined the language’. However, he wasn’t referring to the musical sense, which didn’t arrive until a couple of years later. He meant jazz as a slang term for ‘pep’ or ‘excitement’. It also meant ‘excessive talk, nonsense’. This general sense is still known in the expression and all that jazz, meaning ‘and stuff like that’. As an adjective, it developed a

94.

94.

95.

95.