front of them, for if they did, they would attack without ceasing. Lee is the most wanted man in America. The soldier who captures him will become a legend.

The Union scouts can clearly see the small artillery battery outside Lee’s headquarters, the Turnbull house, and assume that it is part of a much larger rebel force hiding out of sight. Too many times, on too many battlefields, soldiers who failed to observe such discretion have been shot through like Swiss cheese. Rather than rush forward, the Union scouts hesitate, looking fearfully at Lee’s headquarters.

Seizing the moment, Lee escapes. By nightfall, sword still buckled firmly around his waist, Lee crosses the Appomattox River and then orders his army to do the same.

The final chase has begun.

CHAPTER THREE

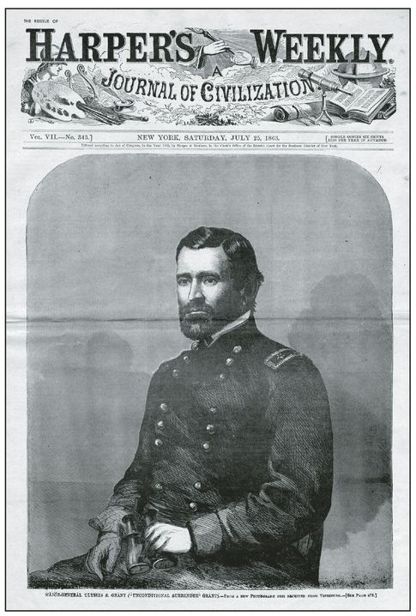

Lee’s retreat is unruly and time-consuming, despite the sense of urgency. So it is, more than eight hours after Lee ordered his army to pull out of Petersburg, that General U. S. Grant can still see long lines of Confederate troops marching across the Appomattox River to the relative safety of the opposite bank. The bridges are packed. A cannon barrage could kill hundreds instantly, and Grant’s batteries are certainly close enough to do the job. All he has to do is give the command. Yes, it would be slaughter, but there is still a war to be won. Killing those enemy soldiers makes perfect tactical sense.

But Grant hesitates.

The war’s end is in sight. Killing those husbands and fathers and sons will impede the nation’s healing. So now Grant, the man so often labeled a butcher, indulges in a rare act of military compassion and simply lets them go. He will soon come to regret it.

For now, his plan is to capture the Confederates, not to kill them. Grant has already taken plenty of prisoners. Even as he watches these rebels escape, Grant is scheming to find a way to capture even more.

The obvious strategy is to give chase, sending the Union army across the Appomattox in hot pursuit. Lee certainly expects that.

But Grant has something different in mind. He aims to get ahead of Lee and cut him off. He will allow the Confederates their unmolested thirty-six-hour, forty-mile slog down muddy roads to Amelia Court House, where the rebels believe food is waiting. He will let them unpack their rail cars and gulp rations to their hearts’ content. And he will even allow them to continue their march to the Carolinas—but only for a while. A few short miles after leaving Amelia Court House, Lee’s army will run headlong into a 100,000-man Union roadblock. This time there will be no river to guard Lee’s rear. Grant will slip that noose around the Confederate army, then yank on its neck until it can breathe no more.

Grant hands a courier the orders. Then he telegraphs President Lincoln at City Point, asking for a meeting. Long columns of rebels still clog the bridges, but the rest of Petersburg is completely empty, its homes shuttered, the civilians having long ago given them over to the soldiers, and soldiers from both sides are now racing across the countryside toward the inevitable but unknown point on the map where they will fight to the death in a last great battle. Abandoned parapets, tents, and cannons add to the eerie landscape. “There was not a soul to be seen, not even an animal in the streets,” Grant will later write. “There was absolutely no one there.”

The five-foot-eight General Grant, an introspective man whom Abraham Lincoln calls “the quietest little man” he’s ever met, has Petersburg completely to himself. He lights a cigar and basks in the still morning air, surrounded by the ruined city that eluded him for 293 miserable days.

He is Lee’s exact opposite: dark-haired and sloppy in dress. His friends call him Sam. “He had,” noted a friend from West Point, “a total absence of elegance.” But like Marse Robert, Grant possesses a savant’s aptitude for warfare—indeed, he is capable of little else. When the Civil War began he was a washed-up, barely employed West Point graduate who had been forced out of military service, done in by lonely western outposts and an inability to hold his liquor. It was only through luck and connections that Grant secured a commission in an Illinois regiment. But it was tactical brilliance, courage under fire, and steadfast leadership that saw him rise to the top.

The one and only time he met Lee was during the Mexican War. Robert E. Lee was already a highly decorated war hero, while Grant was a lieutenant and company quartermaster. He despised being in charge of supplies, but it taught him invaluable lessons about logistics and the way an army could live off the land through foraging when cut off from its supply column. It was after one such scrounge in the Mexican countryside that the young Grant returned to headquarters in a dirty, unbuttoned uniform. The regal Lee, Virginian gentleman, was appalled when he caught sight of Grant and loudly chastised him for his appearance. It was an embarrassing rebuke, one the thin-skinned, deeply competitive Grant would never forget.

Lee isn’t the only Confederate general Grant knows from the Mexican War. James “Pete” Longstreet, now galloping toward Amelia Court House, is a close friend who served as Grant’s best man at his wedding. At Monterrey, Grant rode into battle alongside future Confederate president Jefferson Davis. There are scores of others. And while he’d known many at West Point, it was in Mexico that Grant learned how they fought under fire— their strengths, weaknesses, tendencies. As with the nuggets of information he’d learned as a quartermaster, Grant tucked these observations away and then made keen tactical use of them during the Civil War—just as he is doing right now, sitting alone in Petersburg, thinking of how to defeat Robert E. Lee once and for all.

Grant lights another cigar—a habit that will eventually kill him—and continues his wait for Lincoln. He hopes to hear about the battle for Richmond before the president arrives. Capturing Lee’s army is of the utmost importance, but both men also believe that a Confederacy without a capital is a doomsday scenario for the rebels. Delivering the news that Richmond has fallen will be a delightful way to kick off their meeting.

The sound of horseshoes on cobblestones echoes down the quiet street. It’s Lincoln. Once again the president has courted peril by traveling with just his eleven-year-old son, a lone bodyguard, and a handful of governmental officials. Lincoln knows that, historically, assassination is common during the final days of any war. The victors are jubilant, but the vanquished are furious, more than capable of venting their rage on the man they hold responsible for their defeat.

A single musket shot during that horseback ride from City Point could have ended Lincoln’s life. Despite his profound anxieties about all other aspects of the nation’s future, Lincoln chooses to shrug off the risk. At the edge of Petersburg he trots past “the houses of negroes,” in the words of one Union colonel, “and here and there a squalid family of poor whites”—but no one else. No one, at least, with enough guts to shoot the president. And while the former slaves grin broadly, the whites gaze down with “an air of lazy dislike,” disgusted that this tall, bearded man is once again their president.

Stepping down off his horse, Lincoln walks through the main gate of the house Grant has chosen for their meeting. He takes the walkway in long, eager strides, a smile suddenly stretching across his face, his deep fatigue vanishing at the sight of his favorite general. When he shakes Grant’s hand in congratulation, it is with great gusto. And Lincoln holds on to Grant for a very long time. The president appears so happy that Grant’s aides doubt he’s ever had a more carefree moment in his life.

The air is chilly. The two men sit on the veranda, taking no notice of the cold. They have become a team during the war. Or, as Lincoln puts it, “Grant is my man, and I am his.” One is tall and the other quite small. One is a storyteller, the other a listener. One is a politician; the other thinks that politics is a sordid form of show business. But both are men of action, and their conversation shows deep mutual respect.

Former slaves begin to fill the yard, drawn back into Petersburg by the news that Lincoln himself is somewhere in the city. They stand quietly in front of the house, watching as the general and the president proceed with their private talk. Lincoln is a hero to the slaves—“Father Abraham”—guiding them to the promised land with the Emancipation Proclamation.