Until the empire is recognized for what it is, it is difficult to have a coherent public discussion of its usefulness, its painfulness, and, above all, its inevitability. Unrivaled power is dangerous enough, but unrivaled power that is oblivious is like a rampaging elephant.

I will argue, then, that the next decade must be one in which the United States moves from willful ignorance of reality to its acceptance, however reluctant. With that acceptance will come the beginning of a more sophisticated foreign policy. There will be no proclamation of empire, only more effective management based on the underlying truth of the situation.

Chapter 1

THE UNINTENDED EMPIRE

The American president is the most important political leader in the world. The reason is simple: he governs a nation whose economic and military policies shape the lives of people in every country on every continent. The president can and does order invasions, embargos, and sanctions. The economic policies he shapes will resonate in billions of lives, perhaps over many generations. During the next decade, who the president is and what he (or she) chooses to do will often affect the lives of non-Americans more than the decisions of their own governments.

This was driven home to me on the night of the most recent U.S. presidential election, when I tried to phone one of my staff in Brussels and reached her at a bar filled with Belgians celebrating Barack Obama’s victory. I later found that such Obama parties had taken place in dozens of cities around the world. People everywhere seemed to feel that the outcome of the American election mattered greatly to them, and many appeared personally moved by Obama’s rise to power.

Before the end of Obama’s first year in office, five Norwegian politicians awarded him the Nobel Peace Prize, to the consternation of many who thought that he had not yet done anything to earn it. But according to the committee’s chair, Obama had immediately and dramatically changed the world’s perception of the United States, and this change alone merited the prize. George W. Bush had been hated because he was seen as an imperialist bully. Obama was being celebrated because he signaled that he would not be an imperialist bully.

From the Nobel Prize committee to the bars of Singapore and Sao Paolo, what was being unintentionally acknowledged was the uniqueness of the American presidency itself, as well as a new reality that Americans are reluctant to admit. The new American regime mattered so much to the Norwegians and to the Belgians and to the Poles and to the Chileans and to the billions of other people around the globe because the American president is now in the sometimes awkward (and never explicitly stated) role of global emperor, a reality that the world—and the president—will struggle with in the decade to come.

THE AMERICAN EMPEROR

The American president’s unique status and influence are not derived from conquest, design, or divine ordination but ipso facto are the result of the United States being the only global military power in the world. The U.S. economy is also more than three times the size of the next largest sovereign economy. These realities give the United States power that is disproportionate to its population, to its size, or, for that matter, to what many might consider just or prudent. But the United States didn’t intend to become an empire. This unintentional arrangement was a consequence of events, few of them under American control.

Certainly there was talk of empire before this. Between Manifest Destiny and the Spanish American War, the nineteenth century was filled with visions of empire that were remarkably modest compared to what has emerged. The empire I am talking about has little to do with those earlier thoughts. Indeed, my argument is that the latest version emerged without planning or intention.

From World War II through the end of the Cold War, the United States inched toward this preeminence, but preeminence did not arrive until 1991, when the Soviet Union collapsed, leaving the U.S. alone as a colossus without a counterweight.

In 1796, Washington made his farewell address and announced this principle: “The great rule of conduct for us in regard to foreign nations is in extending our commercial relations, to have with them as little political connection as possible.” The United States had the option of standing apart from the world at that time. It was a small country, geographically isolated. Today, no matter how much the rest of the world might wish us to be less intrusive or how tempting the prospect might seem to Americans, it is simply impossible for a nation whose economy is so vast to have commercial relations without political entanglements or consequences. Washington’s anti-political impulse befitted the anti-imperialist founder of the republic. Ironically, the extraordinary success of that republic made this vision impossible.

The American economy is like a whirlpool, drawing everything into its vortex, with imperceptible eddies that can devastate small countries or enrich them. When the U.S. economy is doing well, it is the engine driving the whole machine; when it sputters, the entire machine can break down. There is no single economy that affects the world as deeply or ties it together as effectively.

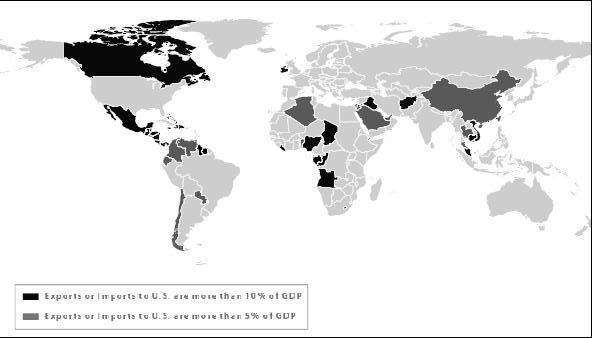

When we look at the world from the standpoint of exports and imports, it is striking how many countries depend on the United States for 5 or even 10 percent of their Gross Domestic Product, a tremendous amount of interdependence. While there are bilateral economic relations and even multilateral ones that do not include the United States, there are none that are unaffected by the United States. Everyone watches and waits to see what the United States will do. Everyone tries to shape American behavior, at least a little bit, in order to gain some advantage or avoid some disadvantage.

Historically, this degree of interdependence has bred friction and even war. In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, France and Germany feared each other’s power, so each tried to shape the other’s behavior. The result was that the two countries went to war with each other three times in seventy years. Prior to World War I, the English journalist (later a member of Parliament) Norman Angell wrote a widely read book called

That the world is no longer filled with relatively equal powers easily tempted into military adventures mitigates this danger somewhat. Certainly the dominance of American military power is such that no one country can hope to use main force to fundamentally redefine its relationship with the United States. At the same time, however, we can see that resistance to American power is substantial and that wars have been frequent since 1991.

While America’s imperial power might degrade, power of this magnitude does not collapse quickly except through war. German, Japanese, French, and British power declined not because of debt but because of wars that devastated those countries’ economies, producing debt as one of war’s many by-products. The Great Depression, which swept the world in the 1920s and 1930s, had its roots in the devastation of the German economy as a result of World War I and the disruption of trade and financial relations that ultimately spread to encompass the world. Conversely, the great prosperity of the American alliance after 1950 resulted from the economic power that the United States built up—undamaged—during World War II.

Absent a major, devastating war, any realignment of international influence based on economics will be a process that takes generations, if it happens at all. China is said to be the coming power. Perhaps so. But the U.S. economy is 3.3 times larger than China’s. China must sustain an extraordinarily high growth rate for a long time in order to close its gap with the United States. In 2009, the United States accounted for 22.5 percent of all foreign