happened today, the death toll would be staggering.

On the wall of her bedroom was an enlarged black-and-white photograph from the San Francisco earthquake. It showed a young woman, hands on her hips, standing on a hilltop, staring out at the burning city as smoke poured into the clear sky. Holleran saw the haunting photo every day. It helped her put a human face on the disasters she’d spent so much of her life studying, helped her keep the cold numbers in the right perspective.

One of the grad students had gone to the trailer for more beers. When he returned, he told Holleran she had a phone call. The man had left a message, a telephone number and his name, Otto Prable.

Dietz said, “Otto Prable! Now there’s a name from the past. What do you think that man’s worth these days, ten, twenty million?”

Holleran was surprised. She hadn’t seen her former professor in more than three years. Prable was a brilliant man. There was simply no other word for it. He’d become a highly paid consultant since he left the university ten years earlier, a geophysicist who was an expert on weather and climate. He’d done extremely well providing long- range global weather forecasts to clients that included some of America’s largest agribusinesses and utility companies. He’d made a fortune.

Holleran had taken a couple of postdoctoral courses with him on climatology—how hurricanes, drought, volcanic eruptions, and other natural forces influenced the planet’s weather. He was one of the most mesmerizing teachers she’d ever had, a superb lecturer who insisted that his students think for themselves.

He’d been disappointed when he couldn’t persuade her to switch from geology to atmospheric physics. She wondered if he had any idea how close he’d come.

Prable lived just a few hours down the coast in Mesa Verde.

Wondering what he wanted, Holleran walked to the trailer and dialed the number. It rang and rang. Just as she was about to hang up, Prable finally answered.

“I’ve sent you a package,” he said without any introduction or greeting. “A videotape and some computer disks. I’ve also sent you a key to my office. My papers are there. I want you to study the material and do what you think best.”

“Doctor, what’s the matter?” Holleran said. His voice sounded weak, far off. Something in his tone immediately put her on edge.

“I have pancreatic cancer, Elizabeth. It’s terminal. Please watch the video. It will explain everything. It’s very important that you do this as soon as possible.”

The news stunned her. She hadn’t known that Prable was sick.

“Doctor, where’s Joanne? Let me talk to Joanne.” Holleran knew and liked Joanne Prable. She’d taught English literature at Berkeley. A warm, good-humored woman. She and her husband were inseparable.

Prable didn’t answer. Holleran heard his heavy, irregular breathing.

“Please put her on the telephone.”

“Read and study all the materials,” Prable said. “Promise me that.”

“I promise, doctor. Now please put your wife on the line. Let me talk to her.” Afraid he was going to hang up, she wanted to keep him talking. She sensed that something was terribly wrong.

“I can’t do that, Elizabeth,” Prable said after another long pause. “My wife is dead. My dear, beloved Joanne. She wanted me to do it. Begged me to do it. Oh, dear God, and I listened to her.”

NEAR KENTUCKY LAKE

JANUARY 9

11:05 A.M.

ATKINS DROVE BACK TO THE BLACKTOP AND followed the road signs toward Kentucky Lake. He’d noticed a boat marina when he passed near the lake earlier that morning. He wanted to get directions and maybe a cup of coffee. After what he’d just seen, he figured he could use a good jolt of caffeine.

He didn’t know what to think about the horde of rats. They were like frightened lemmings charging for the nearest cliff. He’d heard of rats moving in huge packs but had never seen anything that remotely compared with what he’d just witnessed. It was going to be at the top of the list of things to tell Walt Jacobs.

He and Jacobs went back a long way, since their days together in graduate school at Stanford. Jacobs had gone to Memphis after spending a few years in California with the United States Geological Survey (USGS), the federal agency responsible for studying earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and all manner of seismic hazards. Atkins, who’d just turned forty-two, was with the USGS’s disaster response team. It was his job to visit the sites of severe quakes and examine their effects. He’d just returned from a month-long trip to Peru, where a magnitude 7.3 quake had leveled several villages in the Andes. The

A few days after dropping off his report at USGS headquarters in Reston, Virginia, Atkins had flown to Memphis. Jacobs had invited him to visit what geologists called the “New Madrid Seismic Zone.”

Atkins was looking forward to the meeting. They had a lot to talk about, especially Jacobs’ concern that conditions were ripe for a potentially serious earthquake in that part of the country. Shaped like a gigantic hatchet, the fault line extended roughly 140 miles along the adjoining state lines of Arkansas, Tennessee, Kentucky, and Missouri. It passed through parts of five states and crossed the Mississippi in three places.

Jacobs had faxed him a map that showed the fault with striking clarity. It was clipped to a notebook that lay open next to Atkins on the front seat. As he drove, he glanced at the map again. He still couldn’t believe it.

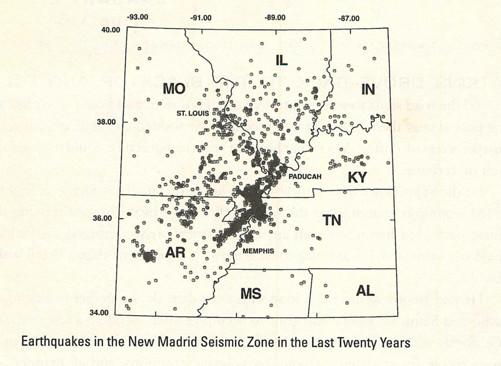

The map showed seismic activity that had occurred in the heart of the Mississippi Valley over the last twenty years. The dots represented the locations of earthquakes over an eight-state area, most of them small, usually less than a magnitude 2 or 3. The hatchet or hammer shape of the fault showed clearly, a darkening where the dots were so thick they overlapped. The handle crossed the boot heel of Missouri and extended into Arkansas. The blade crossed the corners of northwestern Tennessee, southwestern Kentucky, southeastern Missouri, and southern Illinois.

Little known to most Americans, it was one of the most active faults in the world and had produced three of the largest earthquakes on record in North America. The village of New Madrid in the Missouri boot heel was the epicenter for the quakes that struck between December 16, 1811, and February 7, 1812. Thousands of aftershocks had rippled across the Mississippi Valley.

Based on damage reports, all three earthquakes measured a magnitude 8 or greater on the Richter scale.

Atkins found that a little short of staggering.

He was going to meet Jacobs later that day at Reelfoot Lake to discuss the situation. Located forty miles away in northwestern Tennessee, the big lake had been created by the New Madrid earthquakes. Atkins had always wanted to see it.

Along with the scientific data that concerned Jacobs, there’d also been reports of strange animal behavior in the fault zone. Hogs running wild in their pens. Cows butting into each other. Horses slamming around in their stalls. And now rats.

Partly as a favor to his friend and partly out of his own curiosity, Atkins agreed to check out some of the reports before their meeting. Jacobs had given him a list with four or five names, all people who’d called to say their animals were acting up.

Atkins had been trying to find one of these farmers when he got lost on that remote stretch of country road near Benton.

The Chinese had long relied on animals to provide warning signs for earthquakes. In one famous example, in February 1975, a magnitude 7.3 quake hit the city of Haicheng. More than ninety percent of the homes collapsed. Earlier that same day, officials had warned the population that a big quake was imminent. Despite bitter cold, most people moved outdoors. Only a couple hundred people died, and this in a country where it was common for bad quakes to kill thousands. The Chinese partly based their prediction on reports of unusual animal behavior.

Atkins had always been skeptical about using animals as earthquake predictors. And yet the phenomenon