Emily Craig

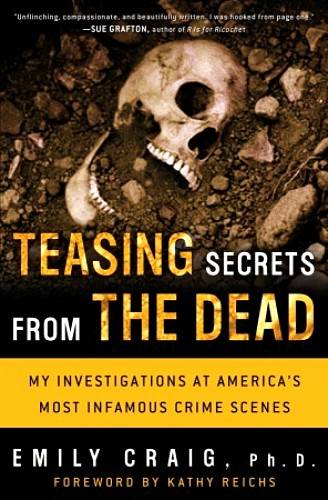

Teasing Secrets from the Dead: My Investigations at America's Most Infamous Crime Scenes

Copyright © 2004 by Emily Craig, Ph.D.

Foreword

I CONFESS. It's a puzzler. After working for years in a profession ignored by the masses, my field is suddenly hot.

Don't get me wrong. The disinterest in my science wasn't exclusive to the general public. When I completed graduate school, it was the rare cop or prosecutor who had heard of forensic anthropology. My colleagues and I were a small group back then, known to few, understood by fewer.

Though our numbers have increased over the years, there are still only sixty board-certified practitioners in North America. Along with the military, only a handful of jurisdictions employ full-time anthropologists. The majority of us still serve as external consultants to law enforcement, coroners, and medical examiners.

But our specialty has come of age. Today every TV viewer in America knows who to call for the skeletal, the burned, the decomposed, the mummified, the mutilated, and the dismembered dead.

Ironic. Forensic science is hardly new. The first treatise may have been penned in China in the thirteenth century. In Sung Tz'u's

The FBI recognized the value of forensic anthropology early, calling upon Smithsonian scientists for help with human remains. By the first half of the twentieth century, T. Dale Stewart and others were working for the military, examining the bones of American soldiers killed in war.

Forensic anthropology became a formally recognized specialty in 1972, when the American Academy of Forensic Sciences created a Physical Anthropology Section. The American Board of Forensic Anthropology was formed shortly thereafter.

Throughout the seventies, the discipline continued to expand, moving into the investigation of human rights abuses. Spurred by pioneers such as Clyde Snow, anthropologists began digging and setting up labs in Argentina, Guatemala, later Rwanda, Kosovo, and elsewhere. Our role grew in the arena of mass/disaster recovery. Through DMORT (Disaster Mortuary Operational Response Team), we worked plane crashes, cemetery floods, bombings, the World Trade Center.

Still, no one knew our name.

Cue

True-crime mini-docs weren't far behind.

And literature was right in there. Patricia Cornwell. Jeffrey Deaver. Karin Slaughter. And, of course, Kathy Reichs, with my forensic anthropologist heroine, Temperance Brennan.

After decades of anonymity, suddenly we are rock stars.

But the public remains somewhat confused as to the players. What's a pathologist? What's an anthropologist? I am asked the question again and again.

Many fictional scientists are

And we don't work alone. While TV glamorizes the individual heroics of the lone scientist or detective, real-life police work involves cooperation. A pathologist may analyze the organs and brain, an entomologist the insects, an odontologist the teeth and dental records, a molecular biologist the DNA, and a ballistics expert the bullets and casings, while the forensic anthropologist examines the bones. Teamwork is essential. In

I like to think that my own novels have played some small part in raising public awareness of forensic anthropology. I describe my experiences through my fictional character, Temperance Brennan. In

Emily's background is unique. For fifteen years she worked as a medical illustrator, translating the intricacies of bones and joints into sketches and sculpture. She found her way into forensic anthropology through a request for a facial approximation of an unidentified corpse washed up along the Chattahoochee River. She never looked back.

I've known Emily Craig since she was a Bill Bass graduate student doing research at the University of Tennessee 's “Body Farm.” In 1998 we coauthored a chapter in my book

When I first heard the proposal for

The first few chapters put my fears to rest.

And, perhaps more poignantly, Emily opens a door to herself as woman and scientist, struggling to balance passion, objectivity, and human vulnerability, to maintain humor and grace in a difficult and often heartrending occupation.

Prologue . The Sting of Death

– MAYA ANGELOU

I HAD ALREADY spent an inordinate amount of time on the victim's eyes, and I was starting to get frustrated. No matter what I did, I couldn't seem to make her look alive.

Early the day before, I'd propped this woman's head up in the middle of my kitchen table, and I'd been working on it ever since. Now it was two a.m.-long past my usual bedtime-but I just couldn't stop.

Maybe if I worked on another part of the face? I ran my fingers over her cold, smooth cheeks, trying to shake the feeling that her lifeless stare was somehow directed at me. Pressing my thumbs against the soft fold that formed her lower lip, I reshaped her frown into a smile. Then I realized with a start what I had done. After everything she'd gone through, how in the world could I imagine this woman smiling?