selves, and consciousness, banging up against the same mysteriousness and eerieness that I first experienced when I was a teen-ager horrified and yet riveted by the awful and awesome physicality of that which makes us be what we are.

An Author and His Audience

Despite its title, this book is not about me, but about the concept of “I”. It’s thus about you, reader, every bit as much as it is about me. I could just as well have called it “You Are a Strange Loop”. But the truth of the matter is that, in order to suggest the book’s topic and goal more clearly, I should probably have called it “‘I’ Is a Strange Loop” — but can you imagine a clunkier title? Might as well call it “I Am a Lead Balloon”.

In any case, this book is about the venerable topic of what an “I” is. And what is its audience? Well, as always, I write in order to reach a general educated public. I almost never write for specialists, and in a way that’s because I’m not really a specialist myself. Oh, I take it back; that’s unfair. After all, at this point in my life, I have spent nearly thirty years working with my graduate students on computational models of analogy-making and creativity, observing and cataloguing cognitive errors of all sorts, collecting examples of categorization and analogy, studying the centrality of analogies in physics and math, musing on the mechanisms of humor, pondering how concepts are created and memories are retrieved, exploring all sorts of aspects of words, idioms, languages, and translation, and so on — and over these three decades I have taught seminars on many aspects of thinking and how we perceive the world.

So yes, in the end, I am a kind of specialist — I specialize in thinking about thinking. Indeed, as I stated earlier, this topic has fueled my fire ever since I was a teen-ager. And one of my firmest conclusions is that we always think by seeking and drawing parallels to things we know from our past, and that we therefore communicate best when we exploit examples, analogies, and metaphors galore, when we avoid abstract generalities, when we use very down-to-earth, concrete, and simple language, and when we talk directly about our own experiences.

The Horsies-and-Doggies Religion

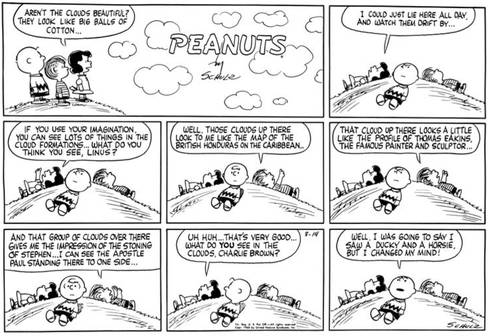

Over the years, I have fallen into a style of self-expression that I call the “horsies-and-doggies” style, a phrase inspired by a charming episode in the famous cartoon “Peanuts”, which I’ve reproduced on the following page.

I often feel just the way that Charlie Brown feels in that last frame — like someone whose ideas are anything but “in the clouds”, someone who is so down-to-earth as to be embarrassed by it. I realize that some of my readers have gotten an impression of me as someone with a mind that enormously savors and indefatigably pursues the highest of abstractions, but that is a very mistaken image. I’m just the opposite, and I hope that reading this book will make that evident.

I don’t have the foggiest idea why I wrongly remembered the poignant phrase that Charlie Brown utters here, but in any case the slight variant “horsies and doggies” long ago became a fixture in my own speech, and so, for better or for worse, that’s the standard phrase I always use to describe my teaching style, my speaking style, and my writing style.

In part because of the success of

I have not followed the standard academic route, which involves publishing paper after paper in professional journals. To be sure, I have published some “real” papers, but mostly I have concentrated on expressing myself through books, and these books have always been written with an eye to maximal clarity.

Clarity, simplicity, and concreteness have coalesced into a kind of religion for me — a set of never-forgotten guiding principles. Fortunately, a large number of thoughtful people appreciate analogies, metaphors, and examples, as well as a relative lack of jargon, and last but not least, accounts from a first-person stance. In any case, it is for people who appreciate that way of writing that this book, like all my others, has been written. I believe that this group includes not only outsiders and amateurs, but also many professional philosophers of mind.

If I tell many first-person stories in this book, it is not because I am obsessed with my own life or delude myself about its importance, but simply because it is the life I know best, and it provides all sorts of examples that I suspect are typical of most people’s lives. I believe most people understand abstract ideas most clearly if they hear them through stories, and so I try to convey difficult and abstract ideas through the medium of my own life. I wish that more thinkers wrote in a first-person fashion.

Although I hope to reach philosophers with this book’s ideas, I don’t think that I write very much like a philosopher. It seems to me that many philosophers believe that, like mathematicians, they can actually

A Few Last Random Observations

I take analogies very seriously, so much so that I went to a great deal of trouble to index a large number of the analogies in my “salad”. There are thus two main headings in the index for my lists of examples. One is “analogies, serious examples of”; the other is “throwaway analogies, random examples of”. I made this droll distinction because whereas many of my analogies play key roles in conveying ideas, some are there just to add spice. There’s another point to be made, though: in the final analysis, virtually every thought in this book (or in any book) is an analogy, as it involves recognizing something as being a variety of something else. Thus every time I write “similarly” or “by contrast”, there is an implicit analogy, and every time I pick a word or phrase (

I initially thought this book was just going to be a distilled retelling of the central message of

Among the keys to