When he wakened, the air was cold and the day was beginning to grow dark. Prince Prigio thought he would go down and dine at a tavern in the town, for no servants had been left with him. But what was his annoyance when he found that his boots, his sword, his cap, his cloak — all his clothes, in fact, except those he wore, — had been taken away by the courtiers, merely to spite him! His wardrobe had been ransacked, and everything that had not been carried off had been cut up, burned, and destroyed. Never was such a spectacle of wicked mischief. It was as if hay had been made of everything he possessed. What was worse, he had not a penny in his pocket to buy new things; and his father had stopped his allowance of fifty thousand pounds a month.

Can you imagine anything more cruel and

Well, here was the prince in a pretty plight. Not a pound in his pocket, not a pair of boots to wear, not even a cap to cover his head from the rain; nothing but cold meat to eat, and never a servant to answer the bell.

CHAPTER V

What Prince Prigio found in the Garret

The prince walked from room to room of the palace; but, unless he wrapped himself up in a curtain, there was nothing for him to wear when he went out in the rain. At last he climbed up a turret-stair in the very oldest part of the castle, where he had never been before; and at the very top was a little round room, a kind of garret. The prince pushed in the door with some difficulty — not that it was locked, but the handle was rusty, and the wood had swollen with the damp. The room was very dark; only the last grey light of the rainy evening came through a slit of a window, one of those narrow windows that they used to fire arrows out of in old times.

But in the dusk the prince saw a heap of all sorts of things lying on the floor and on the table. There were two caps; he put one on — an old, grey, ugly cap it was, made of felt. There was a pair of boots; and he kicked off his slippers, and got into

CHAPTER VI

What Happened to Prince Prigio in Town

By this time the prince was very hungry. The town was just three miles off; but he had such a royal appetite, that he did not like to waste it on bad cookery, and the people of the royal town were bad cooks.

“I wish I were in ‘The Bear,’ at Gluckstein,” said he to himself; for he remembered that there was a very good cook there. But, then, the town was twenty-one leagues away — sixty-three long miles!

No sooner had the prince said this, and taken just three steps, than he found himself at the door of the “Bear Inn” at Gluckstein!

“This is the most extraordinary dream,” said he to himself; for he was far too clever, of course, to believe in seven-league boots. Yet he had a pair on at that very moment, and it was they which had carried him in three strides from the palace to Gluckstein!

The truth is, that the prince, in looking about the palace for clothes, had found his way into that very old lumber-room where the magical gifts of the fairies had been thrown by his clever mother, who did not believe in them. But this, of course, the prince did not know.

Now you should be told that seven-league boots only take those prodigious steps when you say you

Well, the prince walked into “The Bear,” and it seemed odd to him that nobody took any notice of him. And yet his face was as well known as that of any man in Pantouflia, for everybody had seen it, at least in pictures. He was so puzzled by not being attended to as usual, that

“The king,” he said to himself, “has threatened to execute anybody who speaks to me, or helps me in any way. Well, I don’t mean to starve in the midst of plenty, anyhow; here goes!”

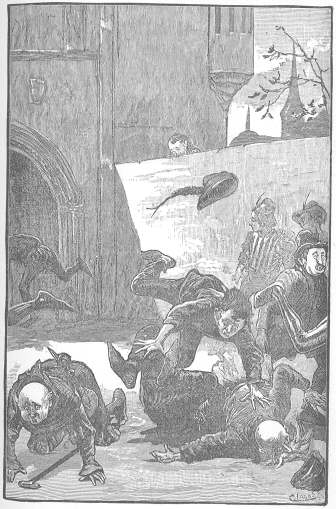

The prince rose, and went to the table in the midst of the room, where a huge roast turkey had just been placed. He helped himself to half the breast, some sausages, chestnut stuffing, bread sauce, potatoes, and a bottle of red wine — Burgundy. He then went back to a table in a corner, where he dined very well, nobody taking any notice of him. When he had finished, he sat watching the other people dining, and smoking his cigarette. As he was sitting thus, a very tall man, an officer in the uniform of the Guards, came in, and, walking straight to the prince’s table, said: “Kellner, clean this table, and bring in the bill of fare.”

With these words, the officer sat down suddenly in the prince’s lap, as if he did not see him at all. He was a heavy man, and the prince, enraged at the insult, pushed him away and jumped to his feet. As he did so,

“Pardon, my prince, pardon! I never saw you!”

This was more than the prince could be expected to believe.

“Nonsense! Count Frederick von Matterhorn,” he said; “you must be intoxicated. Sir! you have insulted your prince and your superior officer. Consider yourself under arrest! You shall be sent to a prison to-morrow.”

On this, the poor officer appealed piteously to everybody in the tavern. They all declared that they had not seen the prince, nor even had an idea that he was doing them the honour of being in the neighbourhood of their town.

More and more offended, and convinced that there was a conspiracy to annoy and insult him, the prince shouted for the landlord, called for his bill, threw down his three pieces of gold without asking for change, and went into the street.

“It is a disgraceful conspiracy,” he said. “The king shall answer for this! I shall write to the newspapers at once!”

He was not put in a better temper by the way in which people hustled him in the street. They ran against him exactly as if they did not see him, and then staggered back in the greatest surprise, looking in every direction for the person they had jostled. In one of these encounters, the prince pushed so hard against a poor old beggar woman that she fell down. As he was usually most kind and polite, he pulled off his cap to beg her pardon, when, behold, the beggar woman gave one dreadful scream, and fainted! A crowd was collecting, and the prince, forgetting that he had thrown down all his money in the tavern, pulled out his purse. Then he remembered what he had done, and expected to find it empty; but, lo, there were three pieces of gold in it! Overcome with surprise, he thrust the money into the woman’s hand, and put on his cap again. In a moment the crowd, which had been staring at him, rushed away in every direction, with cries of terror, declaring that there was a magician in the town, and a fellow who could appear and disappear at pleasure!

By this time, you or I, or anyone who was not so extremely clever as Prince Prigio, would have understood what was the matter. He had put on, without knowing it, not only the seven-league boots, but the cap of darkness, and had taken Fortunatus’s purse, which could never be empty, however often you took all the money out. All those and many other delightful wares the fairies had given him at his christening, and the prince had found them in the