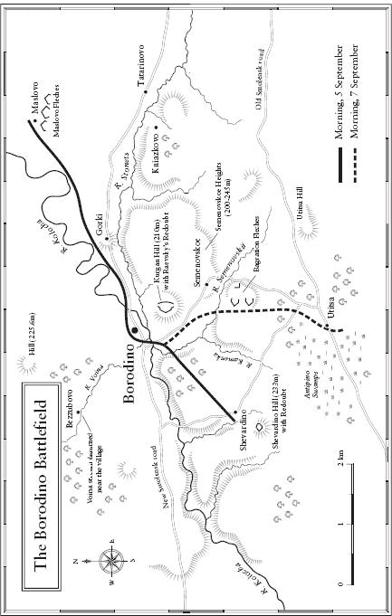

In the era covered by this book Russia ran on the Julian calendar, which in the nineteenth century was twelve days behind the Gregorian calendar used in most of the rest of Europe. The events covered by this book occurred partly in Russia and partly abroad. To avoid confusion, I have used the Gregorian – i.e. European – calendar throughout the text. Documents are cited in the notes in their original form and when they have dates from the Julian calendar the letters OS (i.e. Old Style) appear after them in brackets.

I have used a modified version of the Library of Congress system for transliterating words from Russian. To avoid bewildering anglophone readers I have not included Russian hard and soft signs, accents or stress signs in names of people and places in the text. A point to note is that the Russian

When faced with surnames of non-Russian origin I have tried – not always successfully – to render them in their original Latin version. My own name thereby emerges unscathed as Lieven rather than depressed and reduced as Liven. As regards Christian names I also transliterate for Russians but in general use Western versions for Germans, Frenchmen and other Europeans. So Alexander’s chief of staff is called Petr Volkonsky but General von der Pahlen is rendered as Peter, in deference to his Baltic German origins. No system is perfect in this respect, not least because members of the Russian elite of this era sometimes spelt their own names quite differently according to mood and to the language in which they were writing.

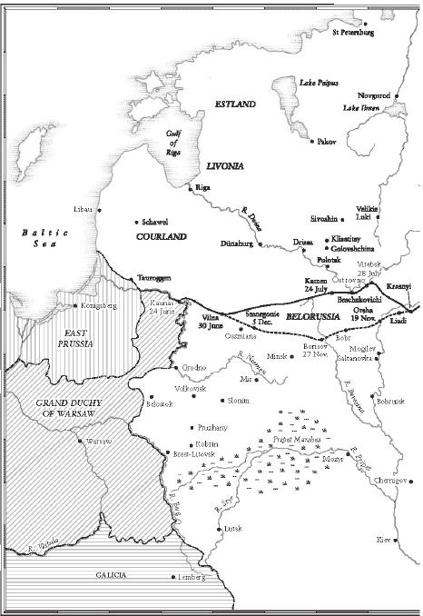

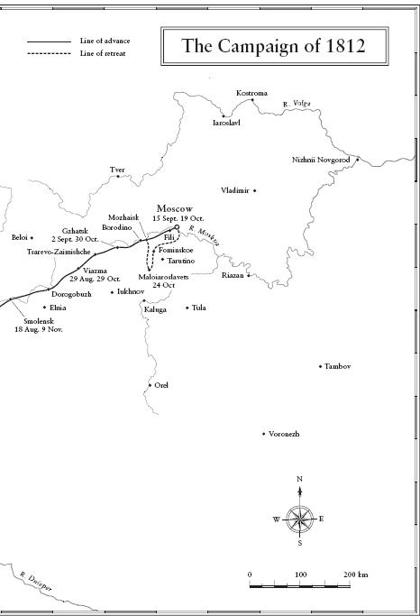

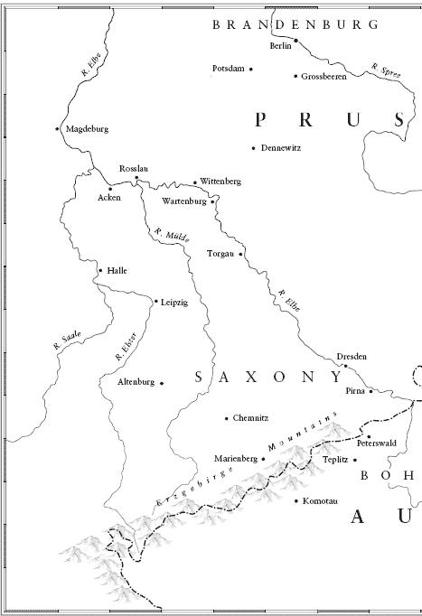

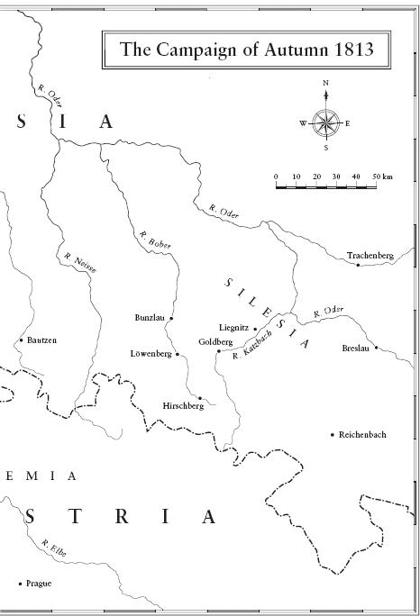

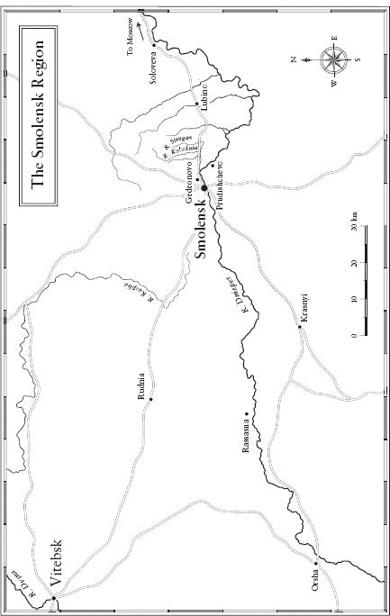

Where an Anglicized version of a town’s name is in common use, I have used it. So Moscow rather than Moskva burns down in this book. But other towns in the Russian Empire are usually rendered in the Russian version, unless the German or Polish version is more familiar to English readers. Towns in the Habsburg Empire and Germany are usually given their German version of a name. This is to simplify the lives of baffled readers trying to follow the movements of armies in texts and maps, though when any doubts might exist alternative versions of place names are given in brackets.

The names of Russian regiments can also be a problem. Above all this boils down to whether or not to use the adjectival version (i.e. ending in