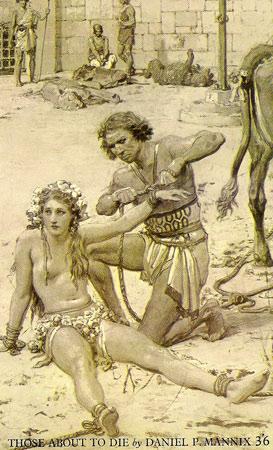

THOSE ABOUT TO DIE

DANIEL P.MANNIX

THE FULL STORY OF THE ROMAN GAMES

TWO ARMIES OF 5,000 MEN FOUGHT TO THE DEATH

THE SHOW WAS LIT AT NIGHT BY HUMAN TORCHES

THEEMPEROR MARCUS SPENTNEARLYA MILLION POUNDS A YEAR ON GLADIATORS

THE COSTLIEST, CRUELLIST SPECTACLE OF ALL TIME

DANIEL P MANNIX

THOSE ABOUT TO DIE

THOSE ABOUT TO DIE

First published in Great Britain by Panther Books Limited 1960

reprinted 1960 (three times),

1961, 1962 (twice), 1963 (twice),

1965 (twice), April 1966

© Copyright 1958 by Daniel P. Mannix

This book shall not? without the written consent of the Publishers first given, be lent, re-sold, hired out or otherwise disposed of by way of trade in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

Printed in England by C. Nicholls & Company Ltd.,

The Philips Park Press, Manchester, and published by Panther Books Ltd., 108 Brompton Road, London, S.W.3

THOSE ABOUT TO DIE

CHAPTER ONE

Nero was Emperor and for two weeks the mob had been rioting uncontrolled in the streets of Rome. The economy of the greatest empire that the world had ever seen was coming apart like an unravelling sweater. The cost of maintaining Rome's gigantic armed forces, equipped with the latest catapults, ballistae, and fast war galleys, was bleeding the nation white and in addition there were the heavy subsidies that had to be paid to the satellite nations dependent on Rome for support. The impoverished government had neither the funds nor the power to stop the riots.

In this crisis, the Captain of the Shipping hurried by chariot to consult with the first tribune.

'The merchant fleet is in Egypt awaiting loading,” he announced. 'The ships can be loaded either with corn for the starving people or with the special sand used on the track for the chariot races. Which shall it

'Are you mad?' screamed the tribune. 'The situation here has got out of control. The emperor's a lunatic, the army's on the edge of mutiny and the people are dying of hunger. For the gods' sake, get the sand! We have to get their minds off their troubles!'

Soon special announcement was made by heralds that the finest chariot races on record would be held at the Circus Maximus. Three hundred pairs of gladiators would fight to the death and twelve hundred condemned criminals would be eaten by lions. Fights between elephants and rhinos, buffaloes and tigers, and leopards and wild boars would be staged. As a special feature, twenty beautiful young girls would be raped by jackasses. Admission to the rear seats, free. Small charge for the first thirty-six tiers of seats.

Everything else was promptly forgotten. The gigantic stadium, seating 385,000 people, was jammed to capacity. For two weeks the games went on while the crowd cheered, made bets and got drunk. Once again the government had a breathing space to try to find some way out of its difficulties.

The games—as these incredible spectacles were politely called—were a national institution. Millions of people were dependent on them for a living: animal trappers, gladiator trainers, horse breeders, shippers, contractors, armourers, stadium attendants, promoters and businessmen of all kinds. To have abolished the games would have thrown so many people out of work that the national economy would have collapsed. In addition, the games were the narcotic that kept the Roman mob doped up so the government could operate. A performer named Pylades contemptuously told Augustus Caesar, 'Your position depends on how we keep the mob amused.' Juvenal wrote bitterly, 'The people who have conquered the world now have only two interests—bread and circuses.'

In a sense, the people were trapped. Rome had over-extended herself. She had become, as much by accident as design, the dominant nation of the world. The cost of maintaining the 'Pax Romana'—the Peace of Rome—over most of the known world was proving too great even for the enormous resources of the mighty empire. But Rome did not dare to abandon her allies or pull back her legions who were holding the barbarian tribes in a line extending from the Rhine in Germany to the Persian Gulf. Every time that a frontier post was relinquished, the wild hordes would sweep in, overrun the area and move just that much closer to the nerve centres of Roman trade.

So the Roman government was constantly threatened by bankruptcy and no statesman could find a way out of the difficulty. The cost of its gigantic military programme was only one of Rome's headaches. To encourage industry in her various satellite nations, Rome attempted a policy of unrestricted trade, but the Roman working-man was unable to compete with the cheap foreign labour and demanded high tariffs. When the tariffs were passed, the satellite nations were unable to sell their goods to the only nation that had any money. To break the deadlock, the government was finally forced to subsidize the Roman working-class to make up the difference between their 'real wages' (the actual value of what they were producing) and the wages required to keep up their relatively high standard of living. As a result, thousands of workmen lived on this subsidy and did nothing what ever, sacrificing their standard of living for a life of ease.

The wealthy class of Rome, living in palaces and eating banquets composed of such delicacies as thrushes' tongues in wild honey and sow's udders stuffed with tried baby mice, owed their riches to great factories where slave labourers produced enormous masses of goods by what we now call assembly-line methods. The dispossessed farmers and unemployed workmen had one great cry: 'Let the rich pay!' The government responded by increasing taxes year after year on the plutocrats, but there was a point beyond which they dared not go. After all, it was the taxes paid by these rich men that kept the whole system going and the government did not dare to ruin them. Attempts were made to abolish slave labour in the factories, but the free workmen's demand for short hours and high wages had grown so great that only slaves could be used economically. Also, the big factory owners were politically powerful and fought every effort to break up their holdings by bribing senators, hiring lobbyists, and securing the support of unscrupulous labour leaders. A Roman factory owner found it far more profitable to spend thousands of sesterces in such practices rather than lose his slaves. And the Roman freeman would far rather have his dole and games than work for a living.

To the Roman mob—caught in an economic tangle it could not comprehend and was unable to break—the circus was the only panacea for its troubles. The great amphitheatres became the ordinary man's temple, home, place of assembly, and ideal. As the games were ostensibly pious ceremonies given in honour of the gods, they gratified his religious sense. He was able for a few hours at least to inhabit an edifice more magnificent than the Golden Palace of Nero instead of a miserable, overcrowded tenement. Here he was able to meet with