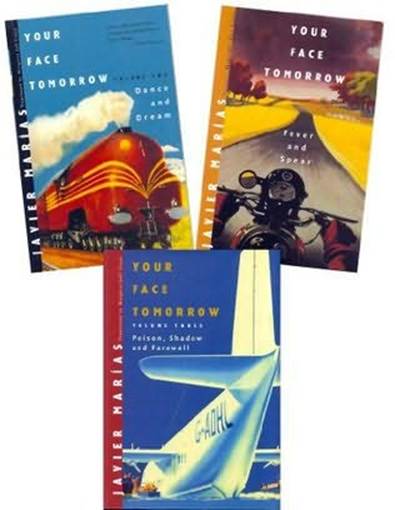

Javier Marias

Your Face Tomorrow 2: Dance and Dream

A book in the Your Face Tomorrow series, 2011

Translated From The Spanish By Margaret Jull Costa

First published with the title Tu rostra manana(2 Baile y Seuno) by Alfaguera, Spain 2004

For Carmen Lopez M, who will, I hope, want to go on listening to me

And for Sir Peter Russell,

to whom this book is indebted

for his long shadow,

and the author,

for his far-reaching friendship

The translator would like to thank Javier Marias, Annella McDermott, Palmira Sullivan, Antonio Martin and Ben Sherriff for all their help and advice.

III Dance

1

Let us hope that no one ever asks us for anything, or even enquires, no advice or favour or loan, not even the loan of our attention, let us hope that others do not ask us to listen to them, to their wretched problems and their painful predicaments so like our own, to their incomprehensible doubts and their paltry stories which are so often interchangeable and have all been written before (the range of stories that can be told is not that wide), or to what used to be called their travails, who doesn't have them or, if he doesn't, brings them upon himself, 'unhappiness is an invention', I often repeat to myself, and these words hold true for misfortunes that come from inside not outside and always assuming they are not misfortunes which are, objectively speaking, unavoidable, a catastrophe, an accident, a death, a defeat, a dismissal, a plague, a famine, or the vicious persecution of some blameless person, History is full of them, as is our own, by which I mean these unfinished times of ours (there are even dismissals and defeats and deaths that are self-inflicted or deserved or, indeed, invented). Let us hope that no one comes to us and says 'Please', or 'Listen' – the words that always precede all or almost all requests: 'Listen, do you know?', 'Listen, could you tell me?', 'Listen, have you got?', 'Listen, I wanted to ask you: for a recommendation, a piece of information, an opinion, a hand, some money, a favourable word, a consolation, a kindness, to keep this secret for me or to change for my sake and be someone else, or to betray and to lie or to keep silent for me and save me.' People ask and ask for all kinds of things, for everything, the reasonable and the crazy, the fair, the outrageous and the imaginary – the moon, as people always used to say, and which was promised by so many people everywhere precisely because it continues to be an imaginary place; people close to us ask, as do strangers, people who are in difficulties and those who caused those difficulties, the needy and the well-to-do, who, in this one respect, are indistinguishable: no one ever seems to have enough of anything, no one is ever contented, no one ever stops, as if they have all been told: 'Ask, just open your mouth and keep asking.' When, in fact, no one is ever told that.

And then, of course, more often than not you listen, feeling fearful sometimes and sometimes gratified too; nothing, in principle, is as flattering as being in a position to concede or refuse something, nothing – as also soon becomes clear – is as sticky and unpleasant: knowing, thinking that one can say 'Yes' or 'No' or 'We'll see'; and 'Perhaps', 'I'll think about it', 'I'll give you an answer tomorrow' or ‘I’ll want this in exchange', depending on your mood and entirely at your discretion, depending on whether you're at a loose end, feeling generous or bored, or, on the contrary, in an enormous hurry and lacking patience and time, depending on how you're feeling or on whether you want to have someone in your debt or to keep them dangling or on whether you want to commit yourself, because when you concede or refuse something – in both cases, even if you have merely lent an ear – you become involved with the supplicant, and you're caught, enmeshed perhaps.

If, one day, you give some money to a local beggar, the following morning it will be harder not to give, because he will expect it (nothing has changed, he is just as poor, I am not as yet any less rich, and why give nothing today when I gave something yesterday) and in a sense you have contracted an obligation with him: by helping him to reach this new day, you have a responsibility not to let this day turn sour on him, not to let it be the day of his final suffering or condemnation or death, and to create a bridge for him to traverse it safely, and so it goes on, one day after another, perhaps indefinitely, there is nothing so very strange or arbitrary about the law found among certain primitive – or perhaps simply more logical – peoples where anyone who saves another person's life becomes that person's guardian and is deemed for ever responsible (unless, one day, the person they saved saves their life and then they can be at peace with each other and go their separate ways), as if the saved person had been empowered to say to his saviour: 'I'm alive today because you wanted me to be; it's as if you had caused me to be born again, therefore you must protect and care for me and keep me safe, because if it wasn't for you, I would be beyond all evil and beyond all harm, or safe more or less in one-eyed, uncertain oblivion.’

And if, on the contrary, you deny alms to your local beggar on that first day, on the second day you will be left with a feeling of indebtedness, an impression that might increase on the third and fourth and fifth days, for if the beggar has negotiated and survived those dates without my help, how can I but commend him and thank him for the money I've saved up until now? And with each morning that passes – each night that he lives through – this idea will put down still deeper roots in us, the idea that we should contribute, that it is our turn. (This, of course, only affects people who notice the ragged; most simply pass them by, adopt an opaque gaze and see them as mere bundles of clothes.) You have only to listen to the beggar who approaches you in the street and you are already involved; you listen to the foreigner or to someone who is lost asking you for directions and sometimes, if you're taking that route yourself, you end up showing them the way, and then the two of you fall into step and you become each other's insistent parallel being which, nevertheless, no one sees as a bad omen or as a nuisance or an obstacle, because you have chosen to walk along together, even though you don't know each other and may not even speak during that time, as the two of you progress (it is the stranger or the person who is lost who can always be led to another place, into a trap, an ambush, to a piece of waste ground, into a snare); and you listen to the stranger who appears at the door persuading or selling or evangelising, trying always to persuade us and always talking very quickly, and just by opening the door to him you are caught; and you listen to the friend on the phone speaking in an urgent, hysterical or mellifluous voice – no, it's definitely hysterical – imploring or demanding or suddenly threatening, and you're already enmeshed; and you listen to your wife and your children who know of almost no other way of talking to you, at least this – asking I mean – is the only way they know of talking to you now, given the growing distance and diffuseness, and then you have to take out a knife or a blade to cut the bond that will eventually tighten around you: you caused them to be born, these children who are not yet beyond all evil or beyond all harm and who never will be, and you caused them to be born to their mother as well, who is like them still because she is now unimaginable without children -they form a nucleus from which none is ever excluded – and they are inconceivable without that figure who is still so necessary to them, so much so that you have no option but to protect her and care for her and keep her safe – you still see this as your task – even though Luisa is not fully aware of it, or not consciously, and even though she is far away in space and moving away from me in time too, date by date and with each day that passes. Even though each night that I negotiate and traverse and survive casts