Chris Nickson

The Broken Token

Here is a token of true love,

We’ll break it into two,

You have my heart and half this ring

Until I find out you.

1

Sometimes he thought he’d been Constable for too long. After fourteen years he believed there was nothing that could shock him any more. He’d seen all of man’s inhumanity to man, not just once, but many times over, and he understood nothing was going to change the way people were. They’d continue to steal and kill whether he caught them or not. All too often he felt he was trying to stem a tide with a bucket. Why, he often wondered, did he persist?

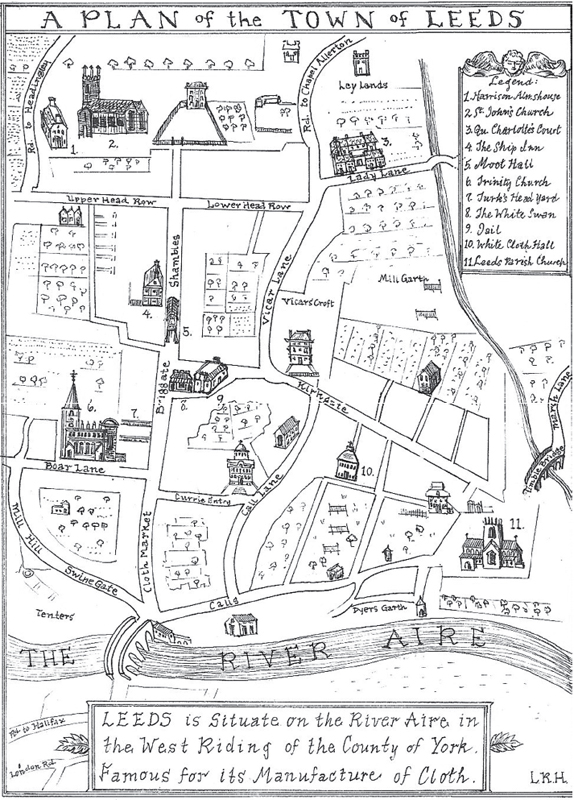

His title certainly sounded grand enough: Richard Nottingham, Constable of the City of Leeds. But for all the fulsome words, it paid barely enough to keep his family in a modest house on Marsh Lane. And to earn it he had to suffer the whims and demands of the Mayor and the aldermen, all of them grown fat and florid off the wool trade. They expected him and his men to solve all the city’s crimes. By the year of Our Lord 1731, that was almost impossible.

He pushed the fringe off his forehead and stretched in his chair. It was ten o’clock on a September night and the raucous noise from the White Swan Tavern next door to the jail filled the air. He’d been working for fifteen hours and he was ready to go home.

He locked the building and walked down Kirkgate, past the shadowed, brooding bulk of the parish church and through York Bar before crossing Timble Bridge to reach Marsh Lane. It took no more than ten minutes, but it felt like an hour as the niggling events of the day played again in his mind. One carter grievously assaulting another over the right of way on Briggate, a drunk tumbling into the River Aire and drowning at Dyers Garth, money and meat stolen from a butcher in the Shambles while his back was turned, and a robbery turned bloody on the Upper Head Row, both thief and victim close to death. Then there was a slippery cutpurse with three victims so far. Plenty of work for today and tomorrow, and for all the days to come. It had been that way from the time, years before, when he’d started as one of the Constable’s men, and worked his way up to deputy and finally Constable.

There was never any shortage of work for the morrow. The poor would always hurt the poor, then die themselves as they performed the hangman’s dance. The rich, though, were never guilty, no matter what they did — and he’d seen them commit crimes others wouldn’t dream about. The wall of property and influence they built around themselves kept the law firmly at bay. He’d tried hammering at it a few times, but one man couldn’t bring down an edifice, even for justice.

As he opened his door the dim light of a candle greeted him, and he smiled to see Mary still awake, her face bent over a book. He knew what it would be —

“I was beginning to wonder if I should go to bed,” she said with a gentle smile.

“It’s been a long day,” Nottingham apologised, shaking his head wearily. “And more of the same tomorrow, by the look of it.”

She stood, the plain fustian of her homespun dress sliding soundlessly as she rose, and he put his arms around her. There was a tranquillity about her features, not quite beautiful but content, and an ease and grace with which she moved. He felt safer with her close, with her warmth and love flowing into him. They’d been married over twenty years now, wed when he still had no idea of his future, and they were just living day to day in a room they shared with her parents.

And even that had seemed wondrous to him then, after growing up in damp, stinking cellars or sleeping rough. He’d known what it was like to be poor in Leeds, leading gangs of children to scavenge for rotten vegetables at the market so they could eat, cutting purses, doing anything he had to in order to survive until the next morning. He’d managed it, but so many hadn’t.

Now he and Mary had an entire house of their own, and two daughters who were growing all too quickly. There was food on the table and coal on the hearth, as long as they weren’t greedy. And he had Mary. He was grateful to her for giving him her love. And in turn he loved her.

The fire had died, but there was still a vestige of its warmth in the room. He settled gratefully into his chair as she brought him bread and cheese and a cup of ale.

“How are the girls?” he asked as he began to eat, realising how hungry he was. When had he eaten last — had it been something in the middle of the day?

“Rose’s man called for her again this evening,” Mary answered, beaming with pleasure. Now almost nineteen, Rose was ready for marriage. “I like him, Richard, I think he’d do well by her.”

“We’ll see,” he answered noncommittally, although he knew the pair were a good match.

“He’s scared of you,” she informed him with a laugh.

“Good.” He gave her a sly smile and a wink. “That way he’ll not be taking advantage of her. And what about Emily? What did the Queen Bee do today?”

“The usual. Flounced around the house after school, expecting to be waited on hand and foot,” Mary said with exasperation, rolling her eyes. At fifteen, Emily seemed to believe that her father’s office elevated her to the gentry, and she expected to be treated that way by everyone, including her own family. Nottingham grimaced. With her attitude the lass will get a shock soon enough, he thought, one that’ll bring her crashing back to earth.

He finished the food, picking the crumbs off the plate. But as he swallowed the last of them, a wave of tiredness seemed to envelop him. He needed sleep. He needed his bed.

He undressed, taking off the stained coat he always wore for work, the smell of wool filling his nostrils as he hung it on a nail driven into the wall. Its style was old and unfashionable, the cuffs reaching back almost to the elbow and the lapels broad as a desk, but it served its purpose, keeping him warm and reasonably dry. His shoes and hose were covered in mud from the courts and alleys where he’d walked all day and much of the evening. The once-elegant pattern on the long waistcoat had faded and rubbed over the years, and his linen shirt had been mended almost everywhere.

Before he slipped into bed Nottingham tied his hair back. As a young man he’d been so proud of his thick, straight blond locks that he’d refused to wear a wig. Instead, he grew it long, letting it flow on to his shoulders, the fringe all too often flopping into his eyes. Now it was thinner, so pale it was almost colourless, but the vanity had become habit; he still refused to follow the fashion of the day by cutting it short and donning a periwig.

Under the chilly sheet and rough blanket, Mary curled against his back, and he lulled himself in the heat of her familiar body. He closed his eyes, his mind skipping between despair and contentment, and hoped not to dream.

2