Pskov's relations with Moscow differed from those of Novgorod. Never a rival of the Muscovite state, Pskov, on the contrary, constantly needed its help against attacks from the west. Thus it fell naturally and rather peacefully under the influence of Moscow. Yet when the Muscovite state finally incorporated Pskov around 1511, the town, after suffering deportations, lost its special institutions, all of its independence, and in the face of Muscovite taxes and regulations, its commercial and middle-class way of life.

In spite of brilliance and many successes, the historical development of Novgorod and Pskov proved to be, in the long run, abortive.

X

At the end of the twelfth century the Russian land has no effective political unity; on the contrary, it possesses several important centers, the evolutions of which, up to a certain point, follow different directions and assume diverse appearances.

While the history of Novgorod represented one important variation on the Kievan theme, two others were provided by the evolutions of the southwestern and the northeastern Russian lands. As in the case of Novgorod, these areas formed parts of Kievan Russia and participated fully in its life and culture. In fact, the southwest played an especially important role in maintaining close links between the Russians of the Kievan period and the inhabitants of eastern and central Europe; whereas the northeast gradually replaced Kiev itself as the political and economic center of the Russian state and also made major contributions to culture, for instance, through its brilliant school of architecture which we discussed earlier. With the collapse of the Kievan state and the breakdown of unity among the Russians, the two areas went their separate ways. Like the development of Novgorod, their independent evolutions stressed certain elements in the Kievan heritage and minimized others to produce strikingly different, yet intrinsically related, societies.

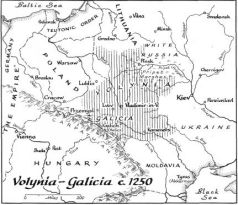

The territory inhabited by the Russians directly west and southwest of the Kiev area was divided into Volynia and Galicia. The larger land, Volynia, sweeps in a broad belt, west of Kiev, from the foothills of the Carpathian Mountains into White Russia. The smaller, Galicia, which is located along the northern slopes of the Carpathians, irrigated by such rivers as the Prut and the Dniester, and bordered by Hungary and Poland, represented the furthest southwestern extension of the Kievan state. During the Kievan period the Russian southwest attracted attention by its international trade, its cities, such as Vladimir-in-Volynia and Galich, as well as many others, and in general by its active participation in the life and culture of the times. Vladimir-in-Volynia, it may be remembered, ranked high as a princely seat, while the entire area was considered among the more desirable sections of the state. The culture of Volynia and Galicia formed

an integral part of Kievan culture, but it experienced particularly strong foreign, especially Western, influences. The two lands played their part in the warfare of the period; Galicia became repeatedly a battleground for the Russians and the Poles.

As Kiev declined, the southwest and several other areas rose in importance. In the second half of the twelfth century Galicia had one of its ablest and most famous rulers, prince Iaroslav Osmomysl, whose obscure appellation has been taken by some scholars to mean 'of eight minds' and to denote his wisdom, and whose power was treated with great respect in the

a lynx, he brought destruction like a crocodile, and he swept over their land like an eagle, brave he was like an aurochs.' Roman died in a Polish ambush in 1205, leaving behind two small sons, the elder, Daniel, aged four.

After Roman's death, Galicia experienced extremely troubled times marked by a rapid succession of rulers, by civil wars, and by Hungarian and Polish intervention. In contrast, Volynia had a more fortunate history, and from 1221 to 1264 it was ruled by Roman's able son Daniel. Following his complete victory in Volynia, which required a number of years, Daniel turned to Galicia and, by about 1238, brought it under his own and his brother's jurisdiction. Daniel also achieved fame as a creator of cities, such as Lvov, which to an extent replaced Kiev as an emporium of East-West trade, a patron of learning and the arts, and in general as a builder and organizer of the Russian southwest. His rule witnessed, in a sense, the culmination of the

Following the death of Daniel in 1264 and of his worthy son and successor Leo in 1301, who had had more trouble with the Mongols, Volynia and Galicia began to decline. Their decline lasted for almost a century and was interrupted by several rallies, but they were finally absorbed by neighboring states. Volynia gradually became part of the Lithuanian state which will be discussed in a later chapter. Galicia experienced intermittently Polish and Hungarian rule until the final Polish success in 1387. Galicia's political allegiance to Poland contributed greatly to a spread of Catholicism and Polish culture and social influences in the southwestern Russian principality, at least among its upper classes. Over a period of time, Galicia lost in many respects its character as one of the Kievan Russian lands.

The internal development of Volynia and Galicia reflected the exceptional growth and power of the boyars. Ancient and well-established on fertile soil and in prosperous towns, the landed proprietors of the southwest often arrogated to themselves the right to invite and depose princes, and they played the leading role in countless political struggles and intrigues. In a most extraordinary development, one of the boyars, a certain Vladislav, even occupied briefly the princely seat of Galicia in 1210, the only occasion in ancient Russia when a princely seat was held by anyone other than a member of a princely family. Vladimirsky-Budanov and other specialists have noted such remarkable activities of Galician boyars as their direct

administration of parts of the principality, in disregard of the prince, and their withdrawal

The northeast, like the southwest, formed an integral part of the Kievan state. Its leading towns, Rostov and Suzdal and some others, belonged with the oldest in Russia. Its princes, deriving from Vladimir Monomakh, participated effectively in twelfth-century Kievan politics. In fact, as we have seen, when Kiev and the Kievan area