emphasized the large scope and vital importance of this free labor and of so-called 'merchant' or 'capitalist' enterprises based on that labor. For instance, in the middle of the century merchants owned some 70 per cent of textile factories in Russia as well as virtually the entire industry of the Moscow and St. Petersburg regions.

In addition to government managers, merchants, and gentry entrepreneurs, businessmen of a different background, including peasants and even serfs, made their appearance. In a number of instances, peasant crafts were gradually industrialized and some former serfs became factory owners, as, for example, in the case of the textile industry in and around

Ivanovo-Voznesensk in central European Russia. Indeed, if we are to follow Poliansky's statistics, peasant participation in industry grew very rapidly and became widespread in the last quarter of the century.

In eighteenth-century Russia the state engaged directly in industrial development but also encouraged private enterprise. This encouragement was plainly evident in such measures as the abolition of various re-

strictions on entering business - notably making it possible for the gentry to take part in every phase of economic life - and the protective tariffs of 1782 and 1793.

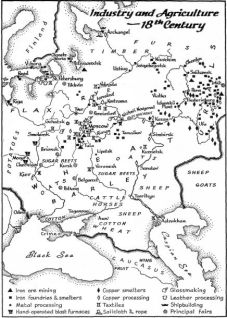

Trade also grew in eighteenth-century Russia. Domestic commerce was stimulated by the repeal of internal tariffs that culminated in Empress Elizabeth's legislation in 1753, by the building of new canals following the example of Peter the Great, by territorial acquisitions, and especially by the quickened tempo and increasing diversity of economic life. In particular, the fertile south sent its agricultural surplus to the center and the north in exchange for products of industries and crafts, while the countryside as a whole supplied the cities and towns with grain and other foods and raw materials. Moscow was the most important center of internal commerce as well as the main distribution and transit point for foreign trade. Other important domestic markets included St. Petersburg, Riga, Archangel, towns in the heart of the grain-producing area such as Penza, Tambov, and Kaluga, and Volga ports like Iaroslavl, Nizhnii Novgorod, Kazan, and Saratov. In distant Siberia, Tobolsk, Tomsk, and Irkutsk developed as significant commercial as well as administrative centers. Many large fairs and uncounted small ones assisted the trade cycle. The best known among them included the celebrated fair next to the Monastery of St. Macarius on the Volga in the province of Nizhnii Novgorod, the fair near the southern steppe town of Kursk, and the Irbit fair in the Ural area.

Foreign trade developed rapidly, especially in the second half of the century. The annual ruble value of both exports and imports more than tripled in the course of Catherine the Great's reign, an impressive achievement even after we make a certain discount for inflation. After the Russian victory in the Great Northern War, the Baltic ports such as St. Petersburg, Riga, and Libau became the main avenue of trade with Russia, and they maintained this dominant position into the nineteenth century. Russia exported to other European countries timber, hemp, flax, tallow, and some other raw materials, together with iron products and certain textiles, notably canvas for sails. Also, the century saw the beginning of the grain trade which was later to acquire great prominence. This trade became possible on a large scale after Catherine the Great's acquisition of southern Russia and the development of Russian agriculture there as well as the construction of the Black Sea ports, notably Odessa which was won from the Turks in 1792 and transformed into a port in 1794. Russian imports consisted of wine, fruits, coffee, sugar, and fine cloth, as well as manufactured goods. Throughout the eighteenth century exports greatly exceeded imports in value. Great Britain remained the best Russian customer, accounting for

something like half of Russia's total European trade. The Russians continued to be passive in their commercial relations with the West: foreign businessmen who came to St. Petersburg and other centers in the empire handled the transactions and carried Russian products away in foreign ships, especially British and Dutch. Russia also engaged in commerce with Central Asia, the Middle East, and even India and China, channeling goods through the St. Macarius Fair, Moscow, Astrakhan, and certain other locations. A considerable colony of merchants from India lived in Astrakhan in the eighteenth century.

Eighteenth-century Russia was overwhelmingly rural. In 1724, 97 per cent of its population lived in the countryside and 3 per cent in towns; by 1796 the figures had shifted slightly to 95.9 per cent as against 4.1 per cent. The great bulk of the people were, of course, peasants. They fell into two categories, roughly equal in size, serfs and state peasants. Toward the end of the century the serfs constituted 53.1 per cent of the total peasant population. As outlined in earlier chapters, the position of the serfs deteriorated from the reign of Peter the Great to those of Paul and Alexander I and reached its nadir around 1800. Increasing economic exploitation of the serfs acompanied their virtually complete dependence on the will of their masters, without even the right to petition for redress. It has been estimated that the obrok increased two and a half times in money value between 1760 and 1800, while the barshchina grew from three to four and in some cases even five or more days a week. It was this striking expansion of the barschina that Emperor Paul tried to stem with his ineffectual law of 1797. Perhaps the most unfortunate were the numerous household serfs who had no land to till, but acted instead as domestic servants or in some other capacity within the manorial household. This segment of the population expanded as landlords acquired new tastes and developed a more elaborate style of life. Indeed, some household serfs became painters, poets, or musicians, and a few even received education abroad. But, as can be readily imagined, it was especially the household serfs who were kept under the constant and complete control of their masters, and their condition could barely be distinguished from slavery. State peasants fared better than serfs, although their obligations, too, increased in the course of the century. At best, as in the case of certain areas in the north, they maintained a reasonable degree of autonomy and prosperity. At worst, as exemplified by possessional workers, their lot could not be envied even by the serfs. On the whole the misery of the Russian

countryside provides ample explanation for the Pugachev rebellion and for repeated lesser insurrections which occurred throughout the century.

By contrast, the eighteenth century, especially the second half during the reign of Catherine the Great, has been considered the golden age of Russian gentry. Constituting a little over one per cent of the population, this class certainly dominated the life of the country. With the lessening and finally the abolition of their service obligations, the landlords took a greater interest in their estates, and some of them also pursued other lines of economic activity, such as manufacturing. The State Lending Bank, established by Catherine the Great in 1786, had as its main task the support of gentry landholding. Moreover, it was the gentry more than any other social group that experienced Westernization most fully and developed the first modern Russian culture. And, of course, the gentry continued to surround the throne, to supply officers for the army, and to fill administrative posts.

While the gentry prospered, the position of the clergy and their dependents declined. This sizable group of Russians, about one per cent of the total - it should be remembered that Orthodox priests marry and raise families - suffered from the anti-ecclesiastical spirit of the age and especially from the secularization of Church lands in 1764. In return for vast Church holdings populated by serfs, the Church received an annual subsidy of 450,000 rubles, representing about one-third of the revenues from the land and utterly insufficient to support the clergy. With time and inflation the value of the subsidy dropped. Never rich, the Russian priests became poorer and more insecure financially after 1764. They had to depend almost entirely on fees and donations from their usually impoverished parishioners. In the country especially the style of life of the priests and their families differed little from that of peasants. In post-Petrine Russia, in contrast to some other European states, the clergy had little wealth or prestige. Largely neglected by historians, the Russian clerical estate has recently received some valuable attention from Freeze and a few other scholars.

Most of the peasants, the gentry, and the clergy lived in rural areas. The bulk of the town inhabitants were divided into three legal categories: merchants, artisans, and workers. These classes were growing: for instance, peasants who established themselves as manufacturers or otherwise successfully entered business became merchants. Nevertheless, none of these classes was numerous or prominent in eighteenth-century Russia. As usual, it was the government that tried to stimulate initiative, public spirit, and a degree of participation in local affairs among the townsmen by such means as the creation of guilds and the charter of 1785 granting urban self- government. As usual, too, these efforts failed.