Europe, without the religious coloration, can be found in the instructions issued in 1804 to the Russian envoy in Great Britain.

The War of the Third Coalition broke out in 1805 when Austria, Russia, and Sweden joined Great Britain against France and its ally, Spain. The combined Austrian and Russian armies suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of Napoleon on December 2, 1805, at Austerlitz. Although Austria was knocked out of the war, the Russians continued to fight and in 1806 even obtained a new ally, Prussia. But the French armies, in a

nineteenth-century version of the

It was the temporary settlement with France that allowed the Russians to fight several other opponents and expand the boundaries of the empire in the first half of Alexander's reign. In 1801 the eastern part of Georgia, an ancient Orthodox country in Transcaucasia, joined Russia, and Russian sway was extended to western Georgia in 1803-10. Hard-pressed by their powerful Moslem neighbors, the Persians and the Turks, the Georgians had repeatedly asked and occasionally received Russian aid. The annexation of Georgia to Russia thus represented in a sense the culmination of a process, and a logical, if by no means ideal, choice for the little Christian nation. It also marked the permanent establishment of Russian authority and power beyond the great Caucasian mountain range.

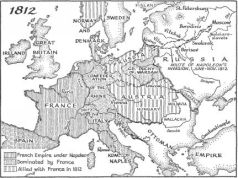

As expected, the annexation of Georgia by Russia led to a Russo-Persian war, fought from 1804 to 1813. The Russians proved victorious, and by the Treaty of Gulistan Persia had to recognize Russian rule in Georgia and cede to its northern neighbor the areas of Daghestan and Shemakha in the Caucasus. The annexation of Georgia also served as one of the causes of the Russo-Turkish war which lasted from 1806 to 1812. Again, Russian troops, this time led by Kutuzov, scored a number of successes. The Treaty of Bucharest, hastily concluded by Kutuzov on the eve of Napoleon's invasion of Russia, added Bessarabia and a strip on the eastern coast of the Black Sea to the empire of the Romanovs, and also granted Russia extensive rights in the Danubian principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia. Finally, in 1808-09 Alexander I fought and defeated Sweden, with the result that the Peace of Frederikshamn gave Finland to Russia. Finland became an autonomous grand duchy with the Russian emperor as its grand duke.

The first half of Alexander's reign also witnessed a continuation of Russian expansion in North America, which had started in Alaska in the late eighteenth century. New forts were built not only in Alaska but also in northern California, where Fort Ross was erected in 1812.

1812

The days of the Russian alliance with Napoleon were numbered. The agreement that the two emperors reached in Tilsit in 1807, and which was renewed at their meeting in Erfurt in 1808, failed in the long run to satisfy either side. The Russians, who were forced to accept it because of their military defeat, resented Napoleon's domination of the continent, his disregard of Russian interests, and, in particular, the obligation to participate in the so-called continental blockade. That blockade, meant to eliminate all commerce between Great Britain and other European countries and to strangle the British economy, actually helped Russian manufactures, especially in the textile industry, by excluding British competition. But it did hurt Russian exporters and thus the powerful landlord class. Russian military reverses at the hands of the French cried for revenge, especially because they came after a century of almost uninterrupted Russian victories. Also, Napoleon, who had emerged from the fearful French Revolution, who had upset the legitimate order in Europe on an unprecedented scale, and who had even been denounced as Antichrist in some Russian propaganda to the masses, appeared to be a peculiar and undesirable ally. Napoleon and his lieutenants, on their part, came to regard Russia as an utterly unreliable partner and indeed as the last major obstacle to their complete domination of the continent.

Crises and tensions multiplied. The French protested the Russian perfunctory, and in fact feigned, participation in Napoleon's war against Austria in 1809, and Alexander I's failure, from 1810 on, to observe the continental blockade. The Russians expressed bitterness over the development of an active French policy in the Near East and over Napoleon's efforts to curb rather than support the Russian position and aims in the Balkans and the Near East: the French opposed Russian control of the Danubian principalities, objected to Russian bases in the eastern Mediterranean, and would not let the Russians have a free hand in regard to Constantinople and the Straits. Napoleon's political rearrangement of central and eastern Europe also provoked Russian hostility. Notably his deposing the Duke of Oldenburg and annexing the duchy to France, a part of the rearrangement in Germany, offended the Russian sovereign who was a close relative of the duke. Still more ominously for Russia, in 1809 after the French victory over Austria and the Treaty of Schonbrunn, West Galicia was added to the Duchy of Warsaw, a state created by Napoleon from Prussian Poland. This change appeared to threaten in turn the hold of Russia on the vast lands that it had acquired in the partitions of Poland. Even Napoleon's marriage to Marie Louise of Austria added to the tension between Russia and France, because it marked the French emperor's

final abandonment of plans to wed a Russian princess, Alexander's sister Anne. Behind specific tensions, complaints, and crises there loomed the fundamental antagonism of two great powers astride a continent and two hostile rulers. In June 1812, having made the necessary diplomatic and military preparations, Napoleon invaded Russia.

France had obtained the support of a number of European states, allies and satellites, including Austria and Prussia: the twelve invading tongues in the popular Russian tradition. Russia had just succeeded in making peace with Turkey, and it had acquired active allies in Sweden and Great Britain. Some 420,000 troops crossed the Russian border with Napoleon to face only about 120,000 Russian soldiers divided into two separate armies, one commanded by Prince Michael Barclay de Tolly and the other by Prince Peter Bagration. Including later reinforcements, an approximate total of 600,000 troops invaded Russia. In addition to its tremendous numbers, Napoleon's army had the reputation of invincibility and what was considered to be an incomparably able leadership. Yet all the advantages were not on one side. Napoleon's

Napoleon advanced into the heart of Russia along the Vilna-Vitebsk-Smolensk line, just as Charles XII had done a century earlier. The Russians could not stop the invaders and lost several engagements to them, including the bloody battle of Smolensk. However, Russian troops inflicted considerable losses on the enemy, repeatedly escaped encirclement, and continued to oppose French progress. Near Smolensk the two separate Russian armies managed to effect a junction and thus present a united front to the invaders. Under the pressure of public opinion incensed by the continuous French advance, Alexander I put Prince Michael Kutuzov in supreme command of the Russian forces. A disciple of Suvorov, and a veteran of many campaigns, the sixty-seven-year-old Kutuzov did agree