such outing we made as a family, marking the first time I came face-to-face with art. I felt a sense of physical identification with the long, languorous Modiglianis; was moved by the elegantly still subjects of Sargent and Thomas Eakins; dazzled by the light that emanated from the Impressionists. But it was the work in a hall devoted to Picasso, from his harlequins to Cubism, that pierced me the most. His brutal confidence took my breath away.

My father admired the draftsmanship and symbolism in the work of Salvador Dali, yet he found no merit in Picasso, which led to our first serious disagreement. My mother busied herself rounding up my siblings, who were sliding the slick surfaces of the marble floors. I’m certain, as we filed down the great staircase, that I appeared the same as ever, a moping twelve-year-old, all arms and legs. But secretly I knew I had been transformed, moved by the revelation that human beings create art, that to be an artist was to see what others could not.

I had no proof that I had the stuff to be an artist, though I hungered to be one. I imagined that I felt the calling and prayed that it be so. But one night, while watching

I shot up several inches. I was nearly five eight and barely a hundred pounds. At fourteen, I was no longer the commander of a small yet loyal army but a skinny loser, the subject of much ridicule as I perched on the lowest rung of high school’s social ladder. I immersed myself in books and rock ’n’ roll, the adolescent salvation of 1961. My parents worked at night. After doing our chores and homework, Toddy, Linda, and I would dance to the likes of James Brown, the Shirelles, and Hank Ballard and the Midnighters. With all modesty I can say we were as good on the dance floor as we were in battle.

I drew, I danced, and I wrote poems. I was not gifted but I was imaginative and my teachers encouraged me. When I won a competition sponsored by the local Sherwin-Williams paint store, my work was displayed in the shopwindow and I had enough money to buy a wooden art box and a set of oils. I raided libraries and church bazaars for art books. It was possible then to find beautiful volumes for next to nothing and I happily dwelt in the world of Modigliani, Dubuffet, Picasso, Fra Angelico, and Albert Ryder.

My mother gave me

Robert Michael Mapplethorpe was born on Monday, November 4, 1946. Raised in Floral Park, Long Island, the third of six children, he was a mischievous little boy whose carefree youth was delicately tinged with a fascination with beauty. His young eyes stored away each play of light, the sparkle of a jewel, the rich dressing of an altar, the burnish of a gold-toned saxophone or a field of blue stars. He was gracious and shy with a precise nature. He contained, even at an early age, a stirring and the desire to stir.

The light fell upon the pages of his coloring book, across his child’s hands. Coloring excited him, not the act of filling in space, but choosing colors that no one else would select. In the green of the hills he saw red. Purple snow, green skin, silver sun. He liked the effect it had on others, that it disturbed his siblings. He discovered he had a talent for sketching. He was a natural draftsman and secretly he twisted and abstracted his images, feeling his growing powers. He was an artist, and he knew it. It was not a childish notion. He merely acknowledged what was his.

The light fell upon the components of Robert’s beloved jewelry kit, upon the bottles of enamel and tiny brushes. His fingers were nimble. He delighted in his ability to piece together and decorate brooches for his mother. He wasn’t concerned that this was a girl’s pursuit, that a jewelry-making kit was a traditional Christmas gift for a girl. His older brother, a whiz at sports, would snicker at him as he worked. His mother, Joan, chain-smoked, and admired the sight of her son sitting at the table, dutifully stringing yet another necklace of tiny Indian beads for her. They were precursors of the necklaces he would later adorn himself with, having broken from his father, leaving his Catholic, commercial, and military options behind in the wake of LSD and a commitment to live for art alone.

It was not easy for Robert to make this break. Something within him could not be denied, yet he also wanted to please his parents. Robert rarely spoke of his youth or his family. He always said he had a good upbringing, that he was safe and well provided for in practical terms. But he always suppressed his real feelings, mimicking the stoic nature of his father.

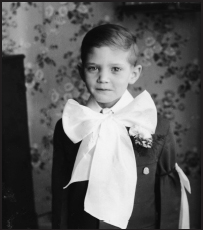

His mother dreamed of him entering the priesthood. He liked being an altar boy, but enjoyed it more for his entrance into secret places, the sacristy, forbidden chambers, the robes and the rituals. He didn’t have a religious or pious relationship with the church; it was aesthetic. The thrill of the battle between good and evil attracted him, perhaps because it mirrored his interior conflict, and revealed a line that he might yet need to cross. Still, at his first holy communion, he stood proud to have accomplished this sacred task, reveling in being the center of attention. He wore a huge Baudelairean bow and an armband identical to the one worn by a very defiant Arthur Rimbaud.

There was no sense of culture or bohemian disorder in his parents’ house. It was neat and clean and a model of postwar middle-class sensibilities, the magazines in the magazine rack, jewelry in the jewelry box. His father, Harry, could be stern and judgmental and Robert inherited these qualities from him, as well as his strong, sensitive fingers. His mother gave him her sense of order and her crooked smile that always made it seem as if he had a secret.

A few of Robert’s drawings were hung on the wall in the hallway. While he lived at home he did his best to be a dutiful son, even choosing the curriculum his father demanded—commercial art. If he discovered anything on his own, he kept it to himself.

Robert loved to hear of my childhood adventures, but when I asked about his, he would have little to say. He said that his family never talked much, read, or shared intimate feelings. They had no communal mythology; no tales of treason, treasure, and snow forts. It was a safe existence but not a fairy-tale one.

“You’re my family,” he would say.

When I was a young girl, I fell into trouble.

In 1966, at summer’s end, I slept with a boy even more callow than I and we conceived instantaneously. I consulted a doctor who doubted my concern, waving me off with a somewhat bemused lecture on the female cycle. But as the weeks passed, I knew that I was carrying a child.

I was raised at a time when sex and marriage were absolutely synonymous. There was no available birth control and at nineteen I was still naive about sex. Our union was so fleeting; so tender that I was not altogether certain we consummated our affection. But nature with all her force would have the final word. The irony that I, who never wanted to be a girl nor grow up, would be faced with this trial did not escape me. I was humbled by nature.

The boy, who was only seventeen, was so inexperienced that he could hardly be held accountable. I would have to take care of things on my own. On Thanksgiving morning I sat on the cot in the laundry room of my parents’ house. This was where I slept when I worked summers in a factory, and the rest of the year while I attended Glassboro State Teachers College. I could hear my mother and father making coffee and the laughter of my siblings as they sat around the table. I was the eldest and the pride of the family, working my way through college. My father was concerned that I was not attractive enough to find a husband and thought that the teaching profession would afford me security. It would be a great blow to him if I did not complete my studies.

I sat for a long time looking at my hands resting on my stomach. I had relieved the boy of responsibility. He was like a moth struggling within a cocoon and I couldn’t bring myself to disturb his unwieldy emergence into the world. I knew there was nothing he could do. I also knew I was incapable of tending to an infant. I had sought the assistance of a benevolent professor who had found an educated couple longing for a child.