more than we could ever have had here. Besides, look into your heart. You all know as well as I do that these hills were never quite right for us. We always needed to head south.”

He took his seat again. On the table were maps of Los Angeles, the western seaboard, and the path through Mexico into Central America. There were places along the way where Lafferty, if he became a tax on the group morale, could be left behind. Those kinds of decisions lay ahead. First came the escape—and the one task remaining before it.

He knew the next to speak would be David Sarno. Sarno had been one of their earliest recruits. He was an ex-industrial farmer who’d become disgusted with genetically modified organisms. A man who knew soil and crops, he also had an authority that could be cultivated. “Based on the average temperatures down there, we won’t have any trouble growing corn or beans, of course. Wheat may be harder, but we don’t need wheat.”

“What does the daykeeper think?” Laura Waller asked. When he had met Laura and recruited her, she was a thirty-two-year-old school-teacher, freshly divorced after four devastating failures at in vitro fertilization. Now she was thirty weeks’ pregnant with the child they had conceived naturally.

“He agrees. South is the only way.”

Lafferty spoke up again. “We need eight trucks to get everything out. How are we going to get that many trucks across the border?”

He shuffl ed the maps quietly. “We’ll get everything in four trucks at most, prioritizing seeds, medical supplies, and weapons.”

The front door opened. The daykeeper. Relief flooded the room at his safe arrival. The daykeeper meant to these people. He was warm. Kind. Compassionate about them and their lives.

“Daykeeper, come, sit. Are you thirsty?”

“I’m fine, Colton. Thank you.”

Victor wiped a bit of sweat from his brow, sat down at the table. “This might be the only peaceful part of L.A. County left,” he said.

Lafferty started to dig back into logistics, but Shetter quickly cut him off. “Thank you all for your counsel. Now would you all give me a few minutes with the daykeeper?”

Shetter kissed Laura on the cheek as she left with the others.

“Are they handling the change of plans?” Victor asked when they were alone.

“They’re afraid,” Shetter said.

“We should all be afraid.”

“But they’re also stronger than they think they are.”

Even before they’d met, Shetter had known Victor’s work. At meetings of his early Internet recruits, Shetter had often read aloud from Victor’s writings on the Long Count. Then, eighteen months ago, the two men had found themselves sitting next to each other at the ritual incense ceremony at the ruins of El Mirador. Shetter knew it couldn’t be a coincidence. They’d been perfect partners from the start. Victor had an unparalleled command of the ancient history and the capacity to inspire their people, and he left the planning to Shetter.

Victor pulled a sheaf of papers from his satchel. “Here are the latest pages that have been translated. If anyone’s still on the fence, this will put their doubts to rest.”

The codex was the final proof of their collective destiny. It showed not only that the ancients had predicted 2012 but that a prescient few had foreseen the collapse and had survived by escaping the cities.

Shetter read the newest sections of the translation. “Someday children will know these lines as well as they know the Pledge of Allegiance. Pretty incredible, don’t you think?” Around Victor, he allowed himself the excitement that he kept from the others.

Victor nodded but seemed distracted.

“Are you all right?” Shetter asked.

“Fine.”

“Do we have a problem?”

“Not at all.”

Shetter slowly shifted back to business, to the details at hand. “Did you get the blueprints?”

“We won’t need them.”

The diagram Victor handed him was just a simple visitor’s map of the Getty Museum. There were no dimensions, no electrical lines, no security schematics. Victor would be invaluable in the new world, but he wasn’t prepared in this one.

“Trust me,” Victor said. “It won’t be difficult to get inside.”

Shetter had already decided not to raise the subject of weapons with the daykeeper. Victor blamed much of the world’s decline on the technology of war; he insisted that their new society must not even speak of such things. So Shetter would oblige him for now, by keeping the Luger P08 in his pocket to himself.

TWENTY-ONE

CHEL AND PATRICK HAD SPENT THE REST OF THE NIGHT AND early morning checking and rechecking the coordinates that suggested a connection between Kiaqix and Paktul’s lost city. She left the observatory just after ten a.m. Patrick was headed back to Martha. As they’d said goodbye beneath the central dome, Chel had realized that she had no idea when she’d see him again, or under what circumstances, and she didn’t like the feeling. So she tried to do again what had always come easily to her before: putting her work first. She sped west, oblivious to the looting, the fires, and the abandoned vehicles all around her.

“He could’ve been one of them,” Rolando’s voice cut in and out over her Bluetooth. What he was suggesting—that the scribe from the lost city could be one of the Original Trio—was slightly less absurd today than it would have been yesterday.

“We don’t even know the city actually exists,” Chel said.

“His spirit animal is a macaw. Wouldn’t he be the perfect candidate to consider thousands of macaws in one place a good omen?”

Chel tried to take the leap from myth to history: A nobleman and his two wives wander the forest after fleeing a city in turmoil. On the third day out, they find a glade where hundreds of scarlet macaws are perched in the trees. Like all the ancient Maya, they believe the birds have great spiritual power. The trio assumes they’ve found an auspicious place to settle in the jungle, and Kiaqix is founded.

“When we finish translating, maybe we’ll see that Paktul married those two little girls, and they became the founders,” Rolando said.

As his voice cut out again, Chel had to swerve around an abandoned Prius in front of the La Brea Tar Pits. Thousands of animals had gotten stuck in the bubbling tar during the last Ice Age, which fossilized everything from mastodons to saber-tooth cats. What would be left of humans here in ten millennia? Chel wondered.

Continuing down Wilshire, she saw graffiti everywhere. The city’s street artists had taken advantage of preoccupied police to tag every available surface: Crip signs, Banksy imitators, and the cartoon initials of freelancers. Then, on the side of a building just west of La Brea Avenue, Chel saw scrawled:

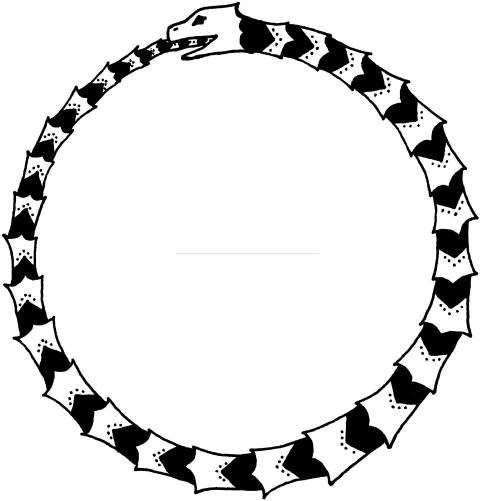

The Maya plumed serpent god—Gukumatz, as the Qu’iche people called it—was sometimes represented by a snake swallowing its own tail. It symbolized the harvest, the cycles of time, and her people’s deep connection to their past. The Greeks called it Ouroboros; to them it had represented something similar. But Chel knew that whoever had painted this intended something else. Gukumatz had been appropriated by the 2012ers, not to symbolize renewal but to evoke the destruction they thought would come with the end of the Long Count cycle—as a reminder that every race of man before ours has been destroyed, devoured by the unrelenting serpent of time.

The signal patched itself back together, and Chel heard Rolando’s voice in her car again. “Hello? Chel, you still there?”

“I’m here. Do me a favor. Put Victor on the phone.”

“Try his cell. He went home to get some journal article from the seventies he thought might help with the Akabalam glyph. Apparently he’s been hoarding back issues for decades.”