classmates laughed at me because I always wore the same jacket with holes everywhere. I wore it all seasons. It was my cousin’s old clothes. Blooming usually wore the clothes after I grew out of them. With patches at the collars and elbows, Coral took over. More patches. The clothes melted, though she was careful. She knew Space Conqueror was waiting for his turn. Space Conqueror always wore rags. It made me feel very guilty.

The kids in the new neighborhood were unfriendly. They attacked us often. We were called “Rags” and “Fleas.” My father said to us, I can’t afford to buy you new clothes to make you look respectable, but if you do well in school you will be respected. The bad kids can take away your school bag but they can’t take away your intelligence. I followed my father’s teaching and it worked. I was soon accepted as a member of the Little Red Guard and was appointed as a head of the Little Red Guard because of my good grades. I was a natural leader. I had early practice at home. In those years, learning to be a revolutionary was everything. The Red Guards showed us how to destroy, how to worship. They jumped off buildings to show their loyalty to Mao. It was said that physical death was nothing. It was light as a feather. Only when one died for the people would one’s death be heavier than a mountain.

My parents never talked about politics at home. They never complained about the labor they were assigned to do. By 1971 my father was no longer a college instructor: he was sent to work in a printing shop as an assistant clerk. Although my mother had a university degree, she was sent to work in a shoe factory. It was a political demand for one to be a member of the working class, said her boss. The Party called it a reeducation program. My parents were unhappy about their jobs, but they behaved correctly for us. If they were ever criticized, it would affect our future.

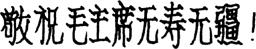

My mother was not good at being someone she was not. Her colleagues said that she was politically clumsy. One day when she was ordered to write on wax paper the slogan “A long, long life to Chairman Mao”:

A long, long life to Chairman Mao!

she wrote “A no, no life to Chairman Mao”:

A no, no life to Chairman Mao!

In Chinese, “A long, long life” translates as “Ten thousand years of no ending,” so there was a character “no” in it. Mother got the characters mixed up and it became “No years of no ending.” It was an accident, my mother said. She was having a severe headache when she was ordered to do the job. She was not allowed to rest when her blood pressure was high. She did not understand why she wrote it the way she did. She always loved Mao, she confessed. She was criticized at the weekly political meeting that everyone in the district had to attend. They said she had an evil intention. She should be treated as a criminal. My mother did not know how to explain herself. She did not know what to do.

I drafted a self-criticism speech for my mother. I was twelve years old. I wrote Mao’s famous quotations. I said Chairman Mao teaches us that we must allow people to correct their mistakes. That’s the only way great Communism is learned. A mistake made by an innocent is not a crime. But when an innocent is not allowed to correct her mistake, it is a crime. To disobey Mao’s teaching is a crime. My mother read my draft at her school meeting and she was forgiven. Mother came home and said to me that she was very lucky to have a smart child like me.

But the next week mother was caught again. She used a piece of newspaper that had Mao’s picture on it to wipe her shit in the toilet room. We all did our wiping with newspapers in those days because very few people could afford toilet paper. Mother showed a doctor’s letter at the masses’ weekly meeting. It proved that her blood pressure was extremely high when the incident took place. She was not forgiven this time. She was sent to be reformed through hard labor in a shoe factory. The factory made rubber boots. Each pair weighed ten pounds. Her job was to take the boots off the molds. Eight hours a day. Every evening she came home and collapsed.

When Mother stepped through the door, she would slide right down on a chair. She sat there, motionless, as if passed out. I would have Blooming get a wet towel and a jar of water, Coral a bamboo fan, Space Conqueror a cup of water, and I myself would take off Mother’s shoes. We then waited quietly until she woke up, and we would begin our service. Mother would smile happily and be served. I would do the wiping of her back, with Blooming fanning. Coral would resoak the towel and pass the towel back to me when Space Conqueror changed the water. By then we would hear our father’s steps on the staircase. We would expect him to open the door and make a mock- face.

We often ran out of food by the end of the month. We would turn into starving animals. In hunger, Coral once dug out a drug bottle from the closet and chewed down pink-colored pills for constipation. She thought it was candy. Her intestine was damaged. Space Conqueror gorged fruit skins and cores he picked from the trash box in the street. Blooming and I drank water while longing for the day to end.

Mother received her salary on the fifth day of each month. We would wait for her on that day at the bus station. When the bus door opened, Mother popped down with her face glittering. We would jump on her like monkeys. She would take us to a nearby bakery to have a full meal. We would keep taking in food until our stomachs became as hard as melons. Mother was the happiest woman on earth at those moments. It was the only day she did not look ill.

My father did not know how to make shoes, but he made shoes for all of us. The shoes he made looked like little boats, with two sides up-because the soles he bought were too small to match the top. He drilled and sewed them together anyway. He used a screwdriver. Every Sunday he repaired our shoes, his fingers wrapped in bandages. He did that until Blooming and I learned how to make shoes with rags.

One day mother came home with a lot of drug bottles. She came from the hospital. She had tuberculosis and was told to wear a surgical mask at home. Mother said that in a way she was pleased to have the disease because she finally got to spend time with her family.

I became a Mao activist in the district and won contests because I was able to recite the Little Red Book.

I became an opera fan. There were not many forms of entertainment. The word “entertainment” was considered a dirty bourgeois word. The opera was something else. It was a proletarian statement. The revolutionary operas created by Madam Mao, Comrade Jiang Ching. To love or not love the operas was a serious political attitude. It meant to be or not to be a revolutionary. The operas were taught on radio and in school, and were promoted by the neighborhood organizations. For ten years. The same operas. I listened to the operas when I ate, walked and slept. I grew up with the operas. They became my cells. I decorated the porch with posters of my favorite opera heroines. I sang the operas wherever I went. My mother heard me singing in my dreams; she said that I was preserved by the operas. It was true. I could not go on a day without listening to the operas. I pasted my ear close to the radio, figuring out the singer’s breaths. I imitated her. The aria was called “I won’t quit the battle until all the beasts are killed.” It was sung by Iron Plum, a teenage character in an opera called

I was able to recite all the librettos of the operas: