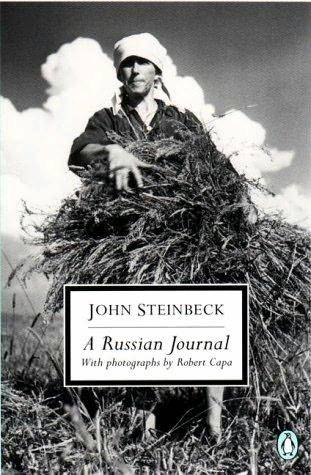

IN 1946, WINSTON CHURCHILL announced that an 'Iron Curtain' I had been drawn closed across Eastern Europe. In the winter of 1947, the cold war began in earnest. The Soviet Union, fierce ally of 1 the United States in World War II, had become a menacing presence, a foe barely understood. 'In the papers every day,' John Steinbeck begins his text, 'there were thousands of words about Russia,' and yet, he continues, 'there were some things that nobody wrote about Russia, and these were the things that interested us most of all.' His quest, and that of photographer Robert Capa who accompanied him, was to discover the 'great other side,' the 'private life of the Russian people.' Steinbeck and Capa's modest book about the lives of Russians, A Russian Journal, published in 1948, attempts only 'honest reporting, to set down what we saw and heard without editorial comment, without drawing conclusions about things we didn't know sufficiently.'

In many ways, that is what John Steinbeck had been doing quite successfully for twenty years, writing books about ordinary people: paisanos, Oklahoma migrants, enlisted men in World War II, Mexican peasants. A Russian Journal does not sound the epic chords of I The Grapes of Wrath, certainly, but it has some of that book's empathy and humanity. Indeed, one explanation for the appeal of A 1 Russian Journal is that this book, unlike so many other accounts of I Russia published at the time, engages and informs in Steinbeck's I most characteristic manner: expressing empathy and understanding I for working people; capturing with a journalist's eye the telling de-1 tail; seeing 'nonteleologically,' recording merely what is witnessed; 1 and finally leavening the narrative with a wry humor absent in I many more ponderous contemporary accounts of travel through I Soviet-approved locales. If not the most erudite or wide-ranging I book about postwar Russia, Steinbeck and Capa's is just what they claimed for it: 'It is not the Russian story, but simply a, Russian story.'

The collaboration between Capa and Steinbeck was, in fact, serendipitous. The two had met in London in 1943, and renewed their friendship in New York in March 1947, planning to leave for Russia as soon as possible, until, on May 14, Steinbeck took a nasty fall from a window of his apartment, shattered his knee, and spent a few weeks recovering (the knee, however, would give him problems throughout the trip). Each restless and independent, neither Capa nor Steinbeck, in fact, particularly cared for collaborative ventures. As early as 1936, when writer John O'Hara passed through Pacific Grove, eager to meet and then work with John Steinbeck on a stage adaptation of the recently published In Dubious Battle, Steinbeck declared that he 'liked him and his attitude… I think we could get along well. I do not believe in collaboration.' Yet despite his protest to the contrary, collaboration came easily to Steinbeck; he initiated or was drawn into several joint projects, many completed-as was his 1940 trip to the Sea of Cortez with marine biologist Edward Ricketts (Sea of Cortez, 1941)-some aborted, as was the one with O'Hara. In particular, Steinbeck gravitated toward visual artists, filmmakers, and photographers. Robert Capa, famed war photo journalist, formed with Steinbeck perhaps the happiest of Steinbeck's alliances with an artist in another medium.

Capa, whose celebrated war photos had frozen individual human torment and exuberance, shared Steinbeck's compassion and curiosity. Born in Budapest, Hungary, in 1913, Capa possessed the qualities of exuberance, tolerance, and a humanitarian spirit that captivated Steinbeck. As biographer Richard Whelan notes, Capa's political philosophy, similar to Steinbeck's own, was formed when Capa was a rebellious teen: 'democratic, egalitarian, pacifistic, semi-collectivist, pro-labor, anti-authoritarian, and anti-fascist, with a strong emphasis on the dignity of man and the rights of the individual.' Forced to leave Budapest in 1931, he had been in exile most of his life, wandering the world as witness to the ravages of war, sometimes shooting photos for Time, Life, and Fortune, always focusing on the human drama, the ordinary in the extraordinary. Capa photographed people, not events, aiming his camera, notes Whelan, on the 'edge of things… studies of people under extreme stress.'

The two artists' forty-day trip to the Soviet Union in 1947 was, like Steinbeck's 1940 trip to the Sea of Cortez with Edward Ricketts, an expedition of the curious. Like Ricketts and Steinbeck on the earlier journey, Capa and Steinbeck also 'wanted to see everything our eyes would accommodate, to think what we could, and, out of our seeing and thinking, to build some kind of structure in modeled imitation of the observed reality.' If the structure of Sea of Cortez melds two approaches, the 'conventionally scientific' and the experiential, this travel narrative opts for the single lens: 'We would try to do honest reporting, to set down what we saw and heard without editorial comment, without drawing conclusions about things we didn't know sufficiently.' Theirs was a journal, a photo essay. The structure they chose for their book-indeed, the dominant metaphor of A Russian Journal- is the Soviet Union as a framed portrait.

With the onset of the 1940s, the world had altered its step. 'Things are very bad in the world, aren't they,' Steinbeck wrote to his editor Pascal Covici in 1940. 'Everything seems to be going to pot, everything as conceived before I mean. Maybe out of the fighting and the struggle there will come some kind of new conceptions. I don't know.' Throughout the 1940s, John Steinbeck sought 'new conceptions' for his own work. He began the decade composing a scientific travelog, ended it working on his most personal and ex-perimental novel, East of Eden. A Russian Journal is part of his ongoing effort to discover fresh material, to forge new literary forms, to rekindle in his writing, as he wrote in his journal during a dark moment in 1946, 'the glory that shadows everything else and that makes me seem like a grey and grizzled animal now… So long since I've done the old kind of work-so long.'

In the late 1930s, John Steinbeck had found that glory while writing his masterpiece, The Grapes of Wrath (1939). For a decade prior, he had been perfecting his craft and publishing in quick suc cession the works most often associated with John Steinbeck, social historian: the short stories in The Long Valley (written in the early 1930s, collected in 1938); the comic tour de force, Tortilla, Flat (1935), and the labor trilogy, In Dubious Battle (1936), Of Mice and Men (1937), and The Grapes of Wrath. By the end of the Depression John Steinbeck, novelist of the people, was a 'household name,' noted the promotional material for the 1940 John Ford film The Grapes of Wrath. That name, however, became something of a burden for the author who had fiercely declared in letters his need for anonymity in order to write. The world's gaze was upon him in the 1940s, expecting high sentiments from this chronicler of the poor. Critics and reviewers waited for the familiar voice of the proletarian writer to return to the gritty themes of the 1930s. He resisted. 'I must make a new start,' he wrote his college roommate, Carlton Sheffield, in November 1939. 'I've worked the novel… as far as I can take it. I never did think much of it-a clumsy vehicle at best. And I don't know the form of the new but I know there is a new thing which will be adequate and shaped by the new thinking.' At the cusp of the new decade, his initial course was scientific and ecological, 'things more lasting,' he remarked to Sheffield. John Steinbeck, novelist, transformed himself into John Steinbeck, marine biologist, as he set out in March 1940 with friend, biologist, and intellectual soul mate Ed Ricketts to explore the littoral of the Sea of Cortez; the 1941 account of that trip, Sea of Cortez, is one of Steinbeck's neglected masterpieces, a