For example, when six senators announced on July 27, 2009, that they were going to eliminate the 'public option'—a government-run insurance policy—from their version of the health care reform bill, the share prices of three major insurance companies surged by between 8% and 10% the next day. Trading stocks in such an environment could be highly profitable, especially if you knew about such events in advance.

One of those at the center of shaping the bill was Senator John Kerry of Massachusetts. Kerry, first elected to the Senate in 1984, had been a longtime advocate of health care reform. He serves as a member of the Health Subcommittee on the powerful Senate Finance Committee. The former Democratic nominee for President is a member of the wealthy Forbes family and is the beneficiary of at least four inherited trusts. In 1995, his wealth jumped dramatically when he married Teresa Heinz, the widow of Pennsylvania Senator John Heinz, heir to the Heinz family fortune. Teresa Heinz Kerry is worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Like other very wealthy people, John Kerry is an investor. His family trusts are relatively small, worth less than $1 million, according to his 2009 financial disclosures. By themselves they could hardly sustain his lifestyle. The bulk of the Kerrys' wealth resides in a series of marital trust and commingled fund accounts. All together, these funds include significant investments in stocks of many corporations. It is his buying and selling of health care stocks during the debate over health care reform that is particularly interesting. While some have reported that the Kerrys' assets are in a blind trust, they have not been designated as such on his financial disclosure forms.2

Contrary to public perception, the major pharmaceutical companies were in favor of Obama's health care bill. The President's new program was expected to increase the demand for prescription drugs by making health care more accessible. Big Pharma, as the companies are collectively known, decided it could not stop the bill, so it might as well try to influence its provisions. Back in 1994, when the Clinton administration (and notably Hillary Clinton) had pushed for dramatic changes in the health care system, several effective ads sponsored by the pharmaceutical industry, starring 'Harry and Louise,' helped defeat 'Hillarycare.' In 2009, Big Pharma hired the two actors again. Only this time they were fifteen years older—and they were in favor of the bill. 'Well, it looks like we may finally get health care reform,' said Harry, in one ad.

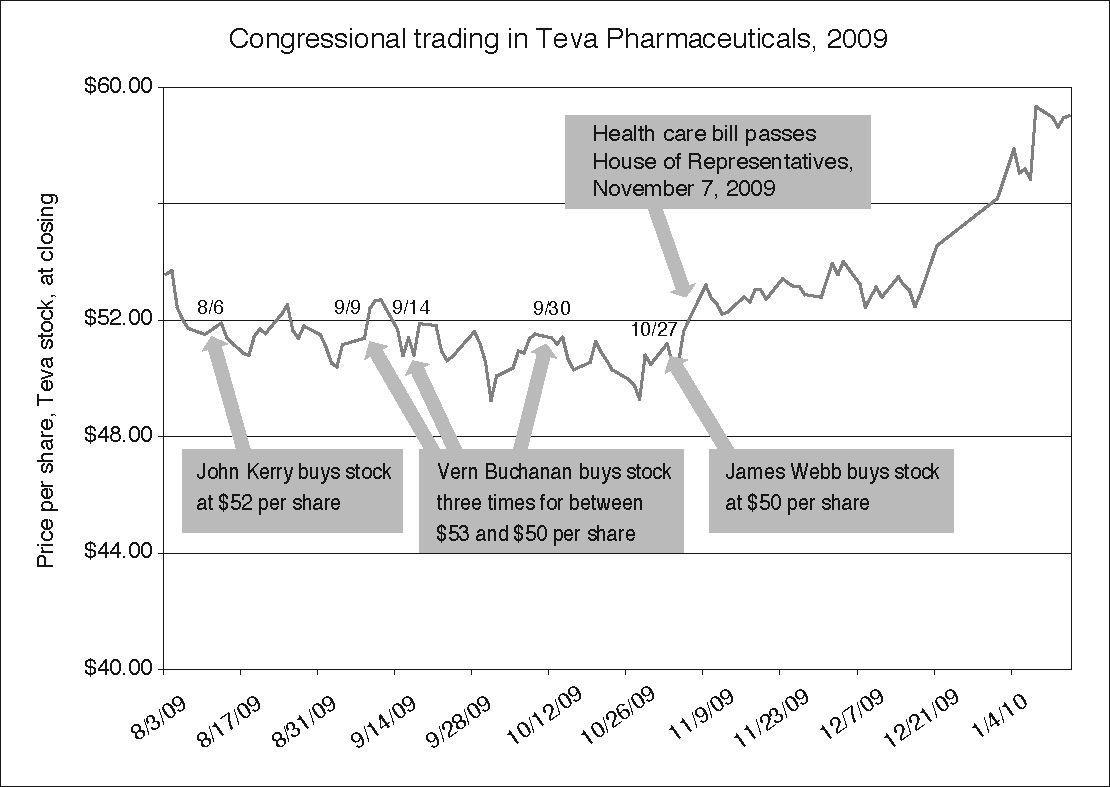

In July 2009, industry representatives met with key members of Congress and hashed out critical details of the new Obama bill.3 As the bill snaked its way through the House and Senate, where Kerry was actively pushing it, the Kerrys began buying stock in the drug maker Teva Pharmaceuticals as the prospects of its passage improved. In November alone they bought close to $750,000 in the company.4

When the Kerrys first began buying shares, the stock was trading at around $50. After health care reform passed, it surged to $62. In 2010, after the reform bill was signed, the Kerrys sold some of their shares in Teva, reaping tens of thousands in capital gains. (It's unclear exactly how much because of the way the transactions are reported. Politicians are required to report ranges only—not exact dollar amounts.) And they held on to more than $1 million worth of Teva shares. All in all, health care stocks proved to be some of the Kerrys' best investments that year, in terms of return on investment.

To be sure, Senator Kerry wasn't the only congressional trader in pharmaceuticals. John Tanner of Tennessee, a member of the House Ways and Means Committee, bought up to $90,000 worth back in April 2009, when the House was approving reserve-fund budgeting for health care (part of the annual budget process). Also buying Teva were Senator Jim Webb of Virginia and Congressman Vern Buchanan of Florida. Unlike Kerry and Webb, however, Buchanan voted against the bill. Casting a vote is one thing; betting on the final tally is something else. Most members, most of the time, know full well which bills will pass before they cast their votes. Health care was such an important bill, and the Democrats had such a strong majority (even if Scott Brown's surprise election in Massachusetts denied them a supermajority of sixty votes in the Senate), that opposing members like Vern Buchanan could still place bets that the bill would eventually get to Obama's desk.

The very idea that politicians trade stocks while they are considering major bills comes as a shock to many people, but it is standard behavior in Washington. Senator Tom Carper of Delaware sat next to Kerry on the Senate Finance Committee's Health Subcommittee. Carper, more of a centrist than Kerry, was concerned about the public option. And according to former Senator Tom Daschle, who was a point man in the Obama administration's push to pass the bill, Carper was intimately involved in hammering together the health care bill throughout the spring, and summer of 2009. By the fall he'd joined a group known as the Gang of Ten, who were trying to bring about a compromise with Republicans.5

PRIMING THE PUMP

Just a few weeks after three committees had approved health care bills in rapid succession, Carper began buying health care stocks that would benefit from the legislation he was supporting. He bought up to $50,000 in Nationwide Health Properties, a real estate investment trust that specialized in health care—related properties. He also picked up shares in Cardinal Health and CareFusion. (As we will see, Cardinal was a popular investment choice for those involved in the health care debate.)

Congresswoman Melissa Bean of Illinois, a moderate, seemed torn over whether to vote for or against Obamacare. But her indecision didn't apply to her stock portfolio. Along with her husband, Bean traded shares as she watched the debate unfold in Washington. Indeed, although Bean and her husband are active traders, the

One of the more creative and cynical plays on health care reform came from Congressman Jared Polis of Colorado. Polis is a young politician who had just taken his congressional seat in January 2009. But he was clearly seen as a rising star, with an appointment to the powerful House Rules Committee. He also sits on the House Democratic Steering and Policy Committee and on the Education and Labor Committee's Subcommittee on Healthy Families and Communities. Polis is wealthy. He grew up amid privilege, and his family became enormously rich after founding and later selling Bluemountain.com, the greeting card website.

Throughout 2009, Polis was a tireless advocate for Obamacare, declaring that health care reform 'could not come at a better time.' Polis sat on two House committees that were central to the crafting and passage of the health care bill. As a member of the House Education and Labor Committee, he was involved in shepherding through one of the three pieces of legislation that would become the final bill. And as a member of the powerful Rules Committee, he helped shape the parameters and procedures to secure passage of the bill in the House.

None of this gave him pause when it came to investing in health care companies as he helped determine the fate of Obamacare. While Polis was praising the benefits of health care overhaul, he was buying millions of dollars' worth of a private company called BridgeHealth International.7 BridgeHealth describes itself as a 'leading health care strategic consultancy.' It works with companies to help them cut health care costs. One of the things that BridgeHealth offers is medical tourism: providing less expensive medical procedures in countries such as China, Mexico, India, Thailand, Costa Rica, and Taiwan. In other words, Polis was betting that there would be more, not less, medical tourism after the passage of health care reform. Companies in the medical tourism industry generally agreed, and favored Obamacare. They did not believe the bill would actually contain costs, and if anything, they expected overseas medical procedures to become more attractive.

After the reform bill became law, BridgeHealth boasted that it was uniquely positioned to help companies cut medical costs. 'What we can offer to the employer and insurer is health care reform today because we've addressed quality and cost,' Vic Lazzaro, BridgeHealth's CEO, said in July 2010 after the bill was passed. 'This is an opportunity to convert that Cadillac plan to a Buick because you can reduce that cost.'9

In all, Polis put between $7 million and $35 million into the company as the health care bill wended its way through Capitol Hill. When investment timing was crucial, Polis's purchases often coincided with the work of his committees. As the Education and Labor Committee considered health care reform in June and July, he made two large purchases of company stock, worth between $1 million and $5 million, on June 16 and 17. His committee passed the health care bill in mid-July. By October 2009, it was Polis's powerful Rules Committee that was determining which amendments would be considered and what the parameters of the debate would be as the House worked to pass the same legislation that was moving forward in the Senate. On October 13 and 23, Polis