“Fuck!”

One of the hoodies crashed over the buggy and the other two were distracted long enough for Steven and Davey to burst through the glass doors of Banburys.

A fat, middle-aged security guard immediately turned towards them, and Steven forced himself to stop running. Davey peered behind them, scared although he didn’t know why.

Outside, the hoodies were hurling insults behind them at the angry mother, and barrelling towards the doors.

“Stevie … ?”

“Ssssh!” Steven jerked his hand to make him pay attention and led him at a sedate pace towards the racks of bags, beads, and belts. The security guard frowned—stymied in his readiness for action now that the two boys had slowed right down and started to look like customers.

The glass doors banged open and the hoodies ran straight into the guard.

Steven looked back as he and Davey stepped onto the escalator. The hoodies were angrily yelling about their rights while the security guard hustled them out of the doors.

“We’ll get you, Lamb!”

Polite shoppers looked around, confused. Steven reddened and looked straight ahead; Davey gripped his hand as if he’d never let go.

Chapter 10

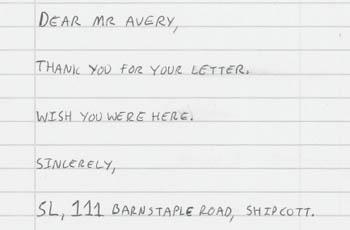

AVERY WAS SURPRISED. THE LETTER SAID NOTHING! IT DID NOT beg, it did not plead, did not offer to help him at his parole hearings—the first of which had already taken place without him, and had led to his transfer from Heavitree to the lower-category Longmoor.

He read the letter again and a slow anger started to smoulder inside him. His own letter had been offhand and cryptic; he knew, because he’d taken some days to work out the precise tone he wanted to convey—ignorant, to get past the censors, and yet with enough of a tease in it to tempt a smart and determined reader into an answer. Avery’s in-tray had been empty for eighteen long years and he barely dared admit even to himself the thrill it gave him to receive a letter. Even more, to receive a letter dealing with his favorite subject. And—the ultimate— to receive a letter from someone connected in some way with the family of one of the children.

SL’s first letter had opened for Arnold Avery a Pandora’s box of memory and excitement. He had started with WP and examined that memory from every aspect; it had taken him days—and those were days when he was no longer held at Her Majesty’s pleasure, but in the grip of his own; days when Officer Finlay’s blue-veined nose lost the power to provoke him; days when being handed a small paper tub of snot instead of mustard with his hamburger was water off a duck’s back. They were days when he was free.

Then he had gone back to the beginning and savored each of the children anew, and prolonged the ecstasy to almost a month’s duration.

And now this letter.

SL had promised to be a serious correspondent but he was a tease. Like a woman! Like a child! In fact, he wouldn’t be surprised if SL was a woman after all! How dare SL start a correspondence and then send him this nothing of a letter? SL could go fuck herself!

Angrily he folded the single A5 sheet to tear it to pieces—then noticed something on the back of the paper.

Avery frowned and held it up to the light but that made it disappear. He tilted the page until he could see what it was. His heart lurched in his chest.

Arnold Avery hammered on his cell door and shouted for a pencil.

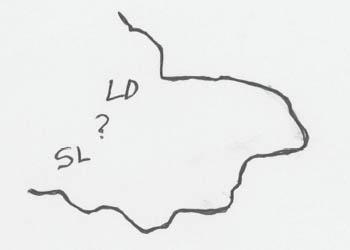

The A5 paper SL had used was good quality. It was better than good quality—it was thick, almost cardlike. Avery had taken art at school and thought it was watercolor paper, with its slightly textured finish.

Avery took a long careful time to rub over the back of the letter with the blunt pencil he’d had to sign for through the hatch.

Drawing on a piece of paper laid over this one, SL (whom he now thought of as a man once more, for the cleverness of this communication) had impressed a single wavering, yet somehow deliberate line which travelled crookedly round from the top of the paper in a large loop. Inside the line were the initials LD and a short way below LD were the initials SL.

The only other symbol impressed on the page was a question mark.

Avery almost laughed. The message was childlike in its simplicity. With a line and four letters which would mean nothing to anyone but him, SL was showing him the outline of Exmoor; he was showing Avery he knew where Luke Dewberry’s body had been found and where he was in relation to that, and he was asking again—where is Billy Peters?

Arnold Avery smiled happily. He had his correspondence.

Chapter 11

WHEN HE WAS YOUNGER, GOOD THINGS SEEMED TO HAPPEN TOO fast for Arnold Avery. Things died too easily and too soon. Birds—which he lured to a seed table and caught in a net—were despicable in their surrender. A friend’s white mouse sat meek and trusting as he stamped on its head. The struggles of Lenny, his grandmother’s fat tabby, were explosive at first but faded quickly as he held it underwater in her bright white bathtub.

None of them challenged him. None of them pleaded, begged, lied, or threatened him. Sure, Lenny had scratched him, but that was avoidable; the next cat he drowned—black and white Bibs—tore madly at the motorcycle gauntlets he’d stolen from a car boot sale.

From an early age he read reports of children snatched from cars or playgrounds and found strangled just hours later, and was confused by the waste. If someone went to all the risk of stealing the ultimate prize—a child —why murder it so shortly after abduction? It made no sense to Avery.

At the age of thirteen he locked a smaller boy in an old coal bunker and kept him there for almost a whole day—afraid to damage him but enjoying the control he had over him. Eight-year-old Timothy Reed had laughed at first, then asked, then demanded, then hammered on the doors, then threatened to tell, then threatened to kill, then had become very, very quiet. After that the pleading had started—the cajoling, the promises, the desperate entreaties, the tears. Avery had been thrilled as much by his own daring as by Timothy’s pathetic cries. He had let him out before it got dark and told him it was a test which he had passed. He and Timothy were now secret friends. The younger boy shook in terror as he agreed that Arnold was his secret friend and never to tell.

And he meant to keep that secret.

After a few weeks of wariness, Timothy Reed started to respond to Arnold’s friendly hellos. He could not help accepting the stolen Scuba Action Man or the pilfered sweets. Two months after the bunker incident, Timothy Reed watched as Arnold tortured a weedy nine-year-old bully to tears and a grovelling apology. The bully sent out word in the playground and Timothy was pathetically grateful to have an older, bigger boy as an ally and protector.