Lettie thumped the fridge door shut and poured the tea into the sink, bags and all—banging the mugs down on the draining board.

Nan shrugged. “These Weetabix suck it up like sponges.”

It was too much.

Lettie grabbed up the brown envelope and ripped it open. Nan eyed her carefully.

“Is that a bill too, then?”

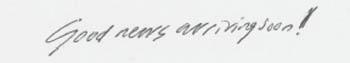

Lettie scanned the page. A meaningless number at the top; not the date. The same as the other two letters. And a brief message.

Good news for whom? Her? Unlikely. Steven? Just as unlikely.

If this was from that girl. If that girl was pregnant. If the baby was due … Only a stupid slag in expectation of a council house could possibly think

Lettie almost squealed with the unfairness of it all. Just as things were looking up! Why could nothing go right and

She almost called Steven downstairs, but the thought of confronting him about something like this while he stood all tousled and sleepy eyed in his little-boy pajamas was more than she could bear.

After a few seconds of brooding, Lettie lit the gas ring and—ignoring her mother’s tutting—burned the letter.

Arnold Avery’s trinket box was full to overflowing. In a few short weeks he had stuffed it with careful observations of casual slips, sneaky shortcuts, skirted regulations, and the failing fabric of the very walls around him. He was almost spoiled for choice.

The keys were the most attractive option—stolen from Ryan Finlay or pressed furtively into his disgusting soap, he could make a mold. Into that mold he would pour wood filler of the type used to repair nicks and chips in old furniture; there was some in the workshop. A coat of varnish to seal and strengthen and he would have the means to stroll from his cell, from his block, from … who knew where? He had narrowed it down to two keys—one opened both the double doors onto the block, the other unlocked one of the four gates in the chain-link which lined the prison wall. Two keys might be enough. One on one side of the soap, one the other. Avery spent long hours practicing little other than the sleight of hand he might need to complete the task—pressing his toothbrush into the bar, gauging the exact degree of push that would yield a workable mold, and rewarding himself with glimpses of the boy reflected in the wing mirror. He rarely allowed himself more—even when he got two perfect impressions in under five seconds. Time—of which he’d once had so much—now seemed precious and fleeting, and Avery kept himself from SL’s photograph as much as possible. He knew that whole days might be lost in the fantasies he wove around the picture. Whole days that it was now vital to spend getting out of prison and replacing the fantasy with the real thing.

He continued to work on the bars of his window at night—his oh-so-versatile toothbrush exposing ever- increasing inches of bar, but with no end in sight either literally or figuratively. Avery didn’t care. His prison-nurtured patience was refined and he continued to work on the window because every grain of grey mortar dust that coated his fingers symbolized potential progress to a goal so desirable that he finally understood what the hell Buddhism was all about.

Avery made a couple more forays into engaging other cons in conversation. Careful ventures which nonetheless earned him one swift “Fuck off, nonce,” and one kick so close to his balls as made no difference, in that it left him curled on the lino, hoarse with fear and hatred—before Andy Ralph stepped between him and his assailant.

So he returned to Ellis, but found there had been a change in the big man’s demeanor. From calm to twitchy; from open to brooding and irritable by turn.

Something had happened.

He had no time to waste waiting for Ellis’s fugue to be over, so he inquired and Ellis told him. Simple as that.

Hilly had been sending Ellis photos and he hadn’t been getting them. Now Hilly thought he didn’t love her anymore. And if Hilly thought he didn’t love her anymore then why would she wait for him? In Ellis’s mind, the chances of him getting those divorce papers had increased a thousandfold. And if Hilly divorced him there’d be nothing to hope for at the end of this soulless, harsh incarceration—no Hilly waiting for his return with a hot kiss, no surprising him at the door in the baby doll nightie she’d got from Ann Summers: no evenings in front of the telly with a bottle of white, no tasting the strawberry lip gloss she wore just for him. He’d never find another woman like Hilly and if she divorced him, they might as well hang him.

By the time he said it, he was close to tears: “They might as well hang me.”

Avery had to keep from laughing. Truly. The melodramatic twit. Hang him! Over lipstick and knickers! People like Ellis

For a moment Avery indulged a sweet fantasy where he looked into those chimpy little eyes all shiny and brimming with monkey emotion, before springing the trapdoor and watching the big man’s dumb head pop off his shoulders.

He wanted to tell Sean Ellis that his whore of a wife wouldn’t have been sending him photos of her tits if she didn’t want them masturbated over by anyone who laid eyes on them.

Instead he told him conspiratorially: “He reads everything, you know. Steals whatever he likes too.”

“Who?” inquired a puzzled Ellis.

“Finlay.” He shrugged.

It never hurt to plant a seed of hatred.

Ryan Finlay had never had occasion to speak to Dr. Leaver. “Mollycoddling” was a word he and his fellow guards tossed about with practiced ease when speaking of their charges, and Finlay felt without thinking that what Leaver did fell neatly into that category along with television privileges and a vegetarian option at mealtimes.

So when Finlay passed Dr. Leaver outside his office door, staring down the corridor after Arnold Avery as the prisoner was led back to his cell one afternoon, it was with no small degree of sarcasm that he inquired: “Another one cured, Doc?”

Leaver flicked his eyes quickly at Finlay, then returned to watching Avery’s disappearing form—flanked as it was by Andy Ralph and Martin Strong, who were charged with keeping him alive on the short journey between blocks.

“Treatment is their right,” he said, a little stiffly.

Finlay snorted but Leaver didn’t look at him. This irritated Finlay. He was used to being listened to at work. Obeyed. Not ignored.

“Those kiddies he killed had rights too, didn’t they?”

Ralph and Strong had reached the barred door at the end of the block. Strong unlocked it while Ralph looked idly at his fingernails. Avery stood to one side—a slight, inoffensive figure beside the two beefy guards.

Leaver finally answered: “Those children were not my patients.”

Fucking bleeding heart! And

“So someone like that gets sent to a cushy nick like this and he does a bit of woodwork and you write your little reports and block up his window and he keeps his nose clean and says, ‘Yes, Dr. Leaver,’ and ‘No, Dr. Leaver,’ but at the end of the day it all means nothing because we’re like a fucking hospital. We just have to patch ‘em up and kick ’em out because we need the beds.”

Hoping to prod Leaver into a response, Finlay had only succeeded in getting all red in the face. He glared at Leaver now but the doctor calmly watched Avery until he’d disappeared from view through the double doors. Then for the first time Leaver turned and looked directly at Finlay—and for the first time the prison officer looked into the eyes that had sought light in the black souls of a thousand twisted killers, and felt a chill straight out of a bad horror film.

“Oh, we’ll always have a bed for Arnold Avery.” Leaver smiled emptily. “He’s going nowhere.”