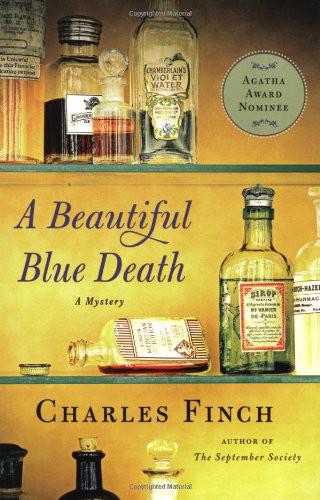

A Beautiful Blue Death

A BEAUTIFUL BLUE DEATH. Copyright © 2007 by Charles Finch. All rights reserved.

To my mother

Acknowledgments

I’m deeply grateful for the help of the following people: Kate Lee, Charles Spicer, Ben Sevier, Jen Crawford, Angela Finch, Charles Finch, Stephen Finch, Sam Truitt, Alex Truitt, Louise Crelly, Harriet Bloomstein, Sam Kusack, Alastair Kusack, Eve Stern, Ben Reiter, Rachel Blitzer, Matt McCarthy, John Phillips, Robin Crawford, Craig Thorn, Frank Turner, and the entire group at Oxford.

And in particular John Hill, Roseanna Hill, Julia Hill, Henry Hill, and Isabelle Hill; my father, who has given me a tremendous amount of support; and my grandmother, who gave me a place to write the book, the confidence to think I could, and the abiding lessons of my life.

A

Beautiful Blue Death

Chapter 1

The fateful note came just as Lenox was settling into his armchair after a long, tiresome day in the city. He read it slowly handed it back to Graham, and told him to throw it away. Its contents gave him a brief moment of preoccupation, but then, with a slight frown, he picked up the evening edition of the

It was a bitterly cold late afternoon in the winter of 1865, with snow falling softly over the cobblestones of London. The clock had just chimed five o’clock, and darkness was dropping across the city—the gas lights were on, the shops had begun to close, and busy men filled the streets, making their way home.

It was the sort of day when Lenox would have liked to sit in his library, tinkering with a few books, pulling down atlases and maps, napping by the fire, eating good things, writing notes to his friends and correspondents, and perhaps even braving the weather to walk around the block once or twice.

But alas, such a day wasn’t meant to be. He had been forced to go down to the Yard, even though he had already given Inspector Exeter what he thought was a tidy narrative of the Isabel Lewes case.

It had been an interesting matter, the widely reported Marlborough forgery—interesting, but, in the end, relatively simple. The family should never have had to call him in. It was such a characteristic failure for Exeter: lack of imagination. Lenox tried to be kind, but the inspector irritated him beyond all reason. What part of the man’s mind forbade him from imagining that a woman, even as dignified a woman as Isabel Lewes, could commit a crime? You could be proper or you could investigate. Not both. Exeter was the sort of man who had joined the Yard partly for power and partly because of a sense of duty, but never because it was his true vocation.

Well, well, at least it was done. His bones were chilled straight through, and he had a pile of unanswered letters on his desk, but at least it was done. He scanned the headlines of the newspaper, which drooped precariously over his legs, and absentmindedly warmed his hands and feet by the large bright fire.

What bliss was there to compare to a warm fire, fresh socks, and buttered toast on a cold day! Ah, and here was his tea, and Lenox felt that at last he could banish Exeter, the Yard, and female criminals from his mind forever.

He sat in a long room on the first floor of his house. Nearest the door was a row of windows that looked out over the street he lived on, Hampden Lane. Opposite the windows was a large hearth, and in front of the hearth were a few armchairs, mostly made of red leather, where he was sitting now, and little tables piled high with books and papers. There were also two leather sofas in the middle of the room, and by the window a large oak desk. On