TABLE OF CONTENTS

PART I: CRIME AND PUNISHMENT

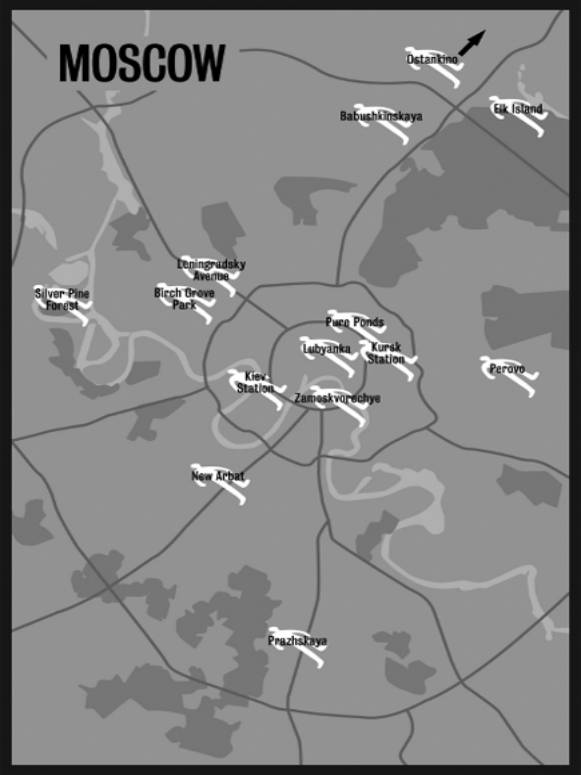

ANNA STAROBINETS Kursk Station

VYACHESLAV KURITSYN Leningradsky Avenue

LUDMILLA PETRUSHEVSKAYA Prazhskaya

ANDREI KHUSNUTDINOV Babushkinskaya

PART II: DEAD SOULS

ALEXANDER ANUCHKIN Elk Island

VLADIMIR TUCHKOV Pure Ponds

IGOR ZOTOV Silver Pine Forest

GLEB SHULPYAKOV Zamoskvorechye

PART III: FATHERS AND SONS

MAXIM MAXIMOV Perovo

IRINA DENEZHKINA New Arbat

SERGEI SAMSONOV Ostankino

PART IV: WAR AND PEACE

DMITRY KOSYREV (MASTER CHEN) Birch Grove Park

ALEXEI EVDOKIMOV Kiev Station

SERGEI KUZNETSOV Lubyanka

About the Contributors

INTRODUCTION

CITY OF BROKEN DREAMS

When we began assembling this anthology, we were dogged by the thought that Russian noir is less about the Moscow of gleaming Bentley interiors and rhinestones on long-legged blondes than it is about St. Petersburg, the empire’s former capital, whose noir atmosphere was so accurately reconstructed by Dostoevsky and Gogol. But the deeper we and the anthology’s authors delved into Moscow’s soul-chilling debris, the more vividly it arose before us in all its bleak and mystical despair. Despite its stunning outward luster, Moscow is above all a city of broken dreams and corrupted utopias, and all manner of scum oozes through the gap between fantasy and reality.

The city comprises fragments of “utterly incommensurate milieus,” notes Grigory Revzin, one of Moscow’s leading journalists, in a recent column. The word “incommensurability” truly captures the feeling you get from Moscow. The complete lack of style, the vast expanses punctuated by buildings between which lie four-century chasms—a wooden house up against a construction of steel—and all of it the result of protracted (more than 850- year) formation. Just a small settlement on the huge map of Russia in 1147, Moscow has traveled a hard path to become the monster it is now. Periods of unprecedented prosperity have alternated with years of complete oblivion.

The center of a sprawling state for nearly its entire history, Moscow has attracted diverse communities, who have come to the city in search of better lives—to work, mainly, but also to beg, to glean scraps from the tables of hard-nosed merchants, to steal and rob. The concentration of capital allowed people to tear down and rebuild ad infinitum; new structures were erected literally on the foundations of the old. Before the 1917 Revolution, buildings demolished and resurrected many times over created a favorable environment for all manner of criminal and quasi- criminal elements. After the Revolution, the ideology did not simply encourage destruction but demanded it. The Bolshevik anthem has long defined the public mentality: “We will raze this world of violence to its foundations, and then/We will build our new world: he who was nothing will become everything!”

Back to the notion of corrupted utopias: much was destroyed, but the new world remained an illusion. Those who had nothing settled in communal apartments. After people were evicted from their private homes and comfortable apartments, dozens of families settled in these spaces, whereupon a new Soviet collective existence was created. (Professor Preobrazhensky, the hero of Mikhail Bulgakov’s

The story of the Cathedral of Christ the Savior is a fairly graphic symbol of how Moscow was “built.” The church was constructed in the late nineteenth century on the site of a convent, which was dismantled and then blown up in 1931, on Stalin’s order, for the construction of the Palace of Soviets. The Palace of Soviets was never built (whether for technical or ideological reasons is not clear), and in its place the huge open-air Moskva Pool was dug out by 1960; it existed until the 1990s, when on the same site they began resurrecting the Cathedral of Christ the Savior, symbolizing “new Russia.”

The more you consider the history of Moscow, the more it looks like a transformer that keeps changing its face, as if at the wave of a magic wand. Take Chistye Prudy—Pure Ponds (the setting for Vladimir Tuchkov’s story in this volume)—which is now at the center of Moscow but in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was in the outskirts and was called “Foul” or “Dirty” Ponds. The tax on bringing livestock into Moscow was much higher than the tax on importing meat, so animals were killed just outside the city, and the innards were tossed into those ponds. One can only imagine what the place was like until it finally occurred to some prince to clean out this source of stench, and voila! Henceforth the ponds were “clean.”

There are a great many such stories. Moscow changes rapidly as it attempts to overcome its dirt, poverty, despair, desolation, and evil; nonetheless, it so often ends up right back where it started.