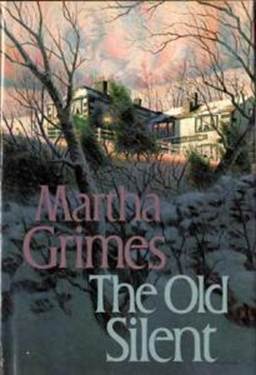

Martha Grimes

The Old Silent

The tenth book in the Richard Jury series, 1989

To

Kathy Grimes

Roy Buchanan

and my cats, Felix and Emily

– Robert Frost

– Richard Hell

Acknowledgments

When asked where I get my inspiration, I say, 'I don't.' This time I did.

I would like to thank some people I've never met: John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Edward Van Halen, Steve Vai, Jeff Beck, Joe Satriani, Ry Cooder, Mark Knopfler, Otis Redding, Eric Clapton, Jimmy Page, James Taylor, Yngwie J. Malmsteen, Elvis Presley, Lester Bangs, Greil Marcus, Jimi Hendrix, John McLaughlin, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Tommy Petty, and Frank Zappa. And many thanks to some people I

– and Melrose Plant

1

He had seen her earlier that day in the museum behind the parsonage. It was ten o'clock in the evening now and since he had been quite certain he wouldn't see her again, Jury couldn't help but keep raising his eyes to look over the top of his local paper to see if, even now, she had the least awareness that she was being observed.

She didn't. She sat back against the cushioned chair by the fireplace, a glass of brandy beside her on the table, largely untouched, as if she'd forgotten it along with her surroundings. Her attention had been for a while fixed (and it was the first suggestion of a smile he had seen all day) on a black cat that had appropriated the best seat in the inn, a brown leather porter's chair with a high, buttoned back. The cat's slow-blinking yellow eyes and proprietorial air seemed to say that guests could come and go, but it would remain. It had rights.

The woman, however, gave the impression that she had none. The beautifully tailored clothes, the square-cut sapphire ring, the perfectly bobbed hair notwithstanding, that was the impression of her he had got earlier-someone who had stepped down, had given over all rights and privileges.

It was a fantasy, and an absurd one at that. From the few scraps of impressions he had stitched together he was in danger of fashioning the tragic history of a queen forced to abdicate.

He tried to go back to his pint of Yorkshire bitter and the engrossing column on the sheep sale and the fund- raiser for the Bronte museum.

It had been in the museum earlier that day that he had first seen her. She was bending over one of the glass cases that protected the manuscripts. It was off-season for tourists, a chilly day after the New Year.

The only other people in the room were a waiflike woman and her balding husband with two young children, all bundled up. In their heavy coats and scarves, the girl and boy resembled the Paddington Bears they carried. The mother looked haggard, in her jeans and baggy sweater, as if she'd just finished up a week's washing; the father, a camera swinging from his shoulder, was trying to read aloud Emily Bronte's poem about a captive bird but was dissuaded by the whines of the kiddies eager to get away from these arcane manuscripts, grim portraits, scents of old leather and beeswax, into the sunnier and more aromatic environs of one of the local tearooms. 'Choc and biscuits' must have been the ritual treat, for they recited it, in tandem, again and again.

The kiddies' whining pleas seemed to awaken the woman in the cashmere coat to a sense of her surroundings, like one awakening in a strange room, one she had entered by mistake and which might harbor some undefined danger. Her expression, indeed, was similar to the one in the touching self-portrait of Branwell Bronte, imagining his own deathbed scene. She looked stricken.

She hitched the strap of the leather bag farther up her shoulder and wandered into the next room. Jury felt she was just as indifferent to the Bronte arcana as the Paddington children had been. She was bending over a case, pushing the tawny hair that fell forward behind her ear as if it blocked her view of Charlotte's narrow boots, her tiny gloves, her nightcap. But that examination was merely cursory as her hand trailed abstractedly along the wooden edge of the case.

Jury studied an old pew door taken from the box pews when the church had been demolished. It bore the legend that a certain lady of 'Crook House, hath 1 sitting.' They must have all had to take turns, back then.

Her slow walk round the display table in Charlotte's room might have given, to a less well-trained eye than his, the impression of absorption. In her eyes was an utter lack of it. The looks she cast here and there were uninquisitive glances from intense and intelligent eyes, but eyes that seemed looking for something else. Or someone. She appeared to be idling there, waiting.

That, he decided, was the impression: her expression preoccupied, the swift, slight turn of the head that