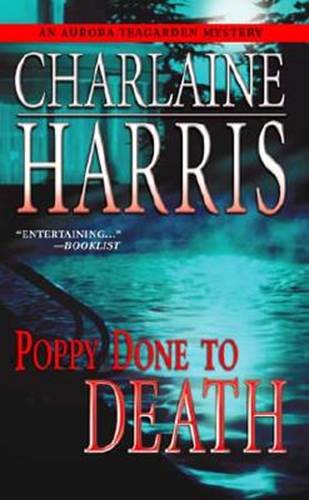

Charlaine Harris

Poppy Done to Death

The eighth book in the Aurora Teagarden series, 2003

To my wonderful “second family,” Christine and Gregg, Bill and Nancy, Joe and Misty, and Tom and Lori. My luck could not have been better.

Acknowledgments

My thanks for the advice of wonderful people like John Ertl, Kate Buker, the Reverend Gary Nowlin, and Michael Silverling. I may not have always used their information and advice correctly, but that fault is only mine. Special thanks to Ann Hilge-man and all the other real Uppity Women.

Prologue

I paid almost no attention at all to the last conversation I had with my stepsister-in-law, Poppy Queensland. Though I liked Poppy-more or less-my main feeling when she called was one of irritation. I was only five years older than Poppy, but she made me feel like a Victorian grandmother, and when she told me she was going to foul up our plans, I felt very… miffed. Doesn’t that sound grumpy?

“Listen,” said Poppy. As always, she sounded imperative and excited. Poppy always made her own life sound more important and exciting than anyone else’s (mine, for example). “I’m going to be late this morning, so you two just go on. I’ll meet you there. Save me a place.”

Later, I figured that Poppy called me about 10:30, because I was almost ready to leave my house to get her, and then Melinda. Poppy and Melinda were the wives of my stepbrothers. Since I’d acquired my new family well into my adulthood, we didn’t have any shared history, and it was taking us a long time to get comfortable. I generally just introduced Poppy and Melinda as my sisters-in-law, to avoid this complicated explanation. In our small Georgia town, Lawrenceton, most often no explanation was required. Lawrenceton is gradually being swallowed by the Atlanta metroplex, but here we still generally know all our family histories.

With the portable phone clasped to my ear, I peered into my bathroom mirror to see if I’d gotten my cheeks evenly pink. But I was too busy thinking that this change of plans was inexplicable and exasperating. “Everything okay?” I asked, wondering if maybe little Chase was sick, or Poppy’s hot-water heater had exploded. Surely only something pretty serious would keep Poppy from this meeting of the Uppity Women, because Poppy was supposed to be inducted into the club this morning. That was a big event in the life of a Lawrenceton woman. Poppy, though not a native, had lived in Lawrenceton since she was a teen, and she surely understood the honor being done her.

Even my mother had never been asked to be an Uppity Woman, though my grandmother had been a member. My mother had always been deemed too focused on her business. (At least that was how my mother explained it.) I was trying awful hard not to be even a little bit smug. It wasn’t often I did anything that made my successful and authoritative mother look at me admiringly.

I think my mother had worked so hard to establish herself- in a business dominated by men-that she didn’t really see the use in lobbying to join an organization made up mostly of homemaking women. Those were the conditions that had existed when she plunged into the workforce to make a living for her tiny family-me. Things had changed now. But you were tapped to join Uppity Women before you were forty-five, or you didn’t join.

What did it take to be an Uppity Woman? The qualifications weren’t exactly spelled out. It was more like they were generally understood. You had to have demonstrated strong-mindedness, and a high degree of resilience. You had to be intelligent, or at least shrewd. You had to be willing to speak out, though that was not an absolute requirement. You couldn’t have any big attitude about what you were: Jewish, or black, or Presbyterian. You didn’t have to have money, but you had to be willing to make an effort to dress appropriately for the meetings. (You would think an organization that encouraged independent women would be really flexible about clothing, but such was not the case.)

You didn’t have to be absolutely Nice. The southern standard of niceness was this: You’d never been convicted of anything, you didn’t look at other’s women’s husbands too openly. You wrote your thank-you notes and were polite to your elders. You had to take a keen interest in your children’s upbringing. And you made sure your family was fed adequately. There were sideways and byways in this “nice” thing, but those were the general have-tos. Poppy was teetering on the edge of not being “nice” enough for the club, and since there had been an Uppity Woman in the forties who’d been just barely acquitted of murdering her husband, that was really saying something.

I shuddered. It was time to think of the positive.

At least we didn’t have to wear hats, as Uppity Women had in the fifties. I would have drawn the line at wearing a hat. Nothing makes me look sillier, whether I wear my hair down (because it’s long and really curly and wavy) or whether I wear it up (which makes my head look huge). I was glad that the Episcopal church no longer required women to wear hats or veils to Sunday service. I would have had to look like an idiot every week.

I’d been mentally digressing, and I’d missed what Poppy said. “What? What was that?” I asked.

But Poppy said, “It’s not important. We’re all fine; I just have to take care of something before I get there. See you later.”

“See you,” I said cheerfully. “What are you wearing to the meeting?” Melinda had asked me to check, because Poppy had a proclivity toward flamboyance in her clothing taste. But I could hardly make Poppy change outfits, as I’d pointed out to Melinda. So I’m not sure why I stretched the conversation out a little more. Maybe I felt guilty for having tuned her out, however briefly; maybe it would have made a difference if I’d listened carefully.

Maybe not.

“Oh, I guess I’ll wear that olive green dress with the matching sweater? And my brown heels. I swear, I think whoever invented panty hose was in league with the devil. I won’t let John David in the room when I’m putting them on. You look like an idiot when you’re wiggling around, trying to get them to stretch enough.”

“I agree. Well, we’ll see you at the meeting.” She wasn’t even dressed yet, I noted.

“Okay, you and Melinda hold up the family banner till I get there.”

That felt strange, but almost good, having a family banner to hold up, even though my inclusion was artificial. My long-divorced mother, Aida Brattle Teagarden, had married widower John Queensland four years ago. Now Melinda and Poppy were her daughters-in-law, married to John’s two sons, Avery and John David. I liked all of the Queenslands, though they certainly were a diverse group.

Probably John’s oldest son, Avery, was my least favorite. But Melinda, Avery’s wife and mother of their two little Queens-lands, was becoming a true friend. At first, I had tended to prefer Poppy, of my two new step in-laws. She was entertaining, bright, and had an original and lively mind. But Melinda, much more prosaic and occasionally given to dim moments, had improved on acquaintance, while Poppy and the way she lived her life had begun to give me pause. Melinda had matured and focused, and she’d broken through her shyness to express her opinions. She was no longer so intimidated by my mother, either. Poppy, who didn’t seem to be scared of anything, took chances, big chances. Unpleasant chances.