Did Vendela know what she was getting herself into? Did she know that sharing her life with Rudbeck would mean sharing his passions? And that this would in turn mean sharing her house with her husband’s stacked paper boxes of seeds, his collection of tobacco pipes, and his indoor gardening ventures, like the cinnamon tree on the ground floor? Did she realize that other rooms in their house would be cluttered with his lutes, paintings, axes, and homemade fireworks?

Almost one year after their wedding, the newlyweds had a terrible scare. Vendela was pregnant with their first child and started experiencing severe pains. Seventeenth-century medicine was, at the best of times, ill equipped to handle unexpected difficulties: primitive anesthetics, crude instruments, and myriad hygienic risks. Women and infants alike died far too often when troubles in childbirth got out of control. For the young couple, too, the situation was critical, and something had to be done.

Although an adjunct professor of medicine, Rudbeck would have had almost no contact with surgery. Nevertheless, he used the skills gained from his many dissections, and performed some sort of surgical maneuver that removed a dangerous obstruction in the birth canal. Older histories called it a Caesarean section, though modern studies have preferred to qualify the position considerably, showing that this was more likely a cutting away of swollen tissue that blocked the opening of the uterus. At any rate, Rudbeck’s operation was a success. Both his wife and son survived, and his contemporaries marveled, ranking it a curiosity of the times. Letters came from France, Germany, and the Royal Society in London requesting further details of the procedure. Rudbeck, it seems, was neither eager to answer their specific questions nor keen to stop the escalating rumors of his medical achievements. Their son was aptly named Johannes Caesar Rudbeck.

At this time, too, authorities recognized the young professor’s talents, and he rose like a rocket through the ranks of the university hierarchy. He was promoted to assistant professor, then full professor, and by 1661 he had been selected to be rector, the highest position at the university. Although expectations were certainly high, no one had any idea of the outburst of energy soon to be unleashed.

ABOUT TWELVE MILES outside of Paris, Louis XIV was busy turning his father’s modest hunting lodge into a palace worthy of the “Sun King.” Some thirty thousand workers labored around the clock to complete the complex of gardens, fountains, and ponds, and of course the enormous palace itself. A fusion of classical dignity and Baroque splendor, Versailles was the epicenter of a country greatly influencing culture on the Continent. What was later said about the Revolution was already applicable to this fashionable trendsetter: “When France caught a cold, Europe sneezed.”

Scandinavia was certainly not immune to the rays of the Sun King and his court. Young dandies were everywhere opting for a more gilded look, complete with powdered wigs, lace scarves, and silk as colorful as peacocks. The cuffs ruffled more, and the French tricorne was placed on the head, or politely raised. Paint and perfume, gloves and handkerchiefs, snuff boxes and walking sticks were added for good measure.

Whims of fashion changed all around him, but Olof Rudbeck kept to his old ways. He preferred a simple black coat, white collar, and knee-length breeches. This attire would have been the height of fashion around 1650, but, as with his long hair, which now flowed naturally onto his shoulders without benefit of a powdered wig, Rudbeck looked increasingly outdated and drew more and more attention for his old-fashioned manner.

He probably appeared a bit eccentric, though in a charming sort of way. His eyes gleamed with hints of mischievousness and flashed with his exuberant love of life. His face was somewhat elongated; his cheeks were rosy. Thin, butterfly-wing whiskers perched above his mouth. His voice was a deep baritone of phenomenal strength, and his laughter often filled the room with mirth.

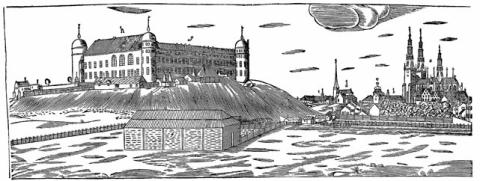

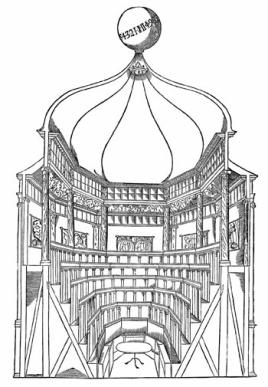

Happily, Rudbeck had taken up his position as rector of Uppsala University. Over the next few years, vitality and exuberance would permeate almost everything he touched. After his pioneering work with the lymphatic system, Rudbeck went on to build an impressive anatomy theater. He actively participated in its construction, from drawing the designs to hammering in the nails, and the building was praised for its architectural wonders. Not least of these was the way in which he managed the light so that it focused on the dissection table at the center, yet avoided casting shadows that would obscure the view from anywhere in the octagonal auditorium. For special occasions, Rudbeck brought out his collection of skeletons, mummies, and even specimens of human skin.

The anatomy theater was actually only one of the prominent landmarks that the city owed to Rudbeck’s efforts. Another was a special institution designed to attract young Swedish aristocrats who might otherwise be tempted to study abroad. This was an elite academy that exercised the body as well as the mind. Built by Rudbeck in 1664–65, this Collegium Illustre had in only a couple of years enrolled fifty-five students who fenced, danced, and rode with skill and flair. Fluent in French, they worked zealously to perfect the gentlemanly arts. This program survived until the late nineteenth century, when the building was torn down and its prime real estate used to house the university administration.

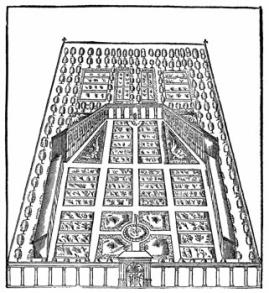

Some contemporaries believed Rudbeck had been born under a lucky star. From the anatomy theater to the botanical garden to the elite exercise academy, visitors could not fail to see his legacy all around town. There was also an apothecary laboratory, a community house to provide free food and shelter to the poor, and a workshop that harnessed the town river to power several machines simultaneously. When his term as rector expired, a new position of curator was created, and Rudbeck was named one of its first officers (along with two others). The multitalented professor had indeed exerted a profound influence over his beloved town and university.

But all that was about to change. By the end of the 1660s, the economy had started to falter. The Swedish copper coin took a nosedive in value, and income from university properties went into startling decline. This meant that salaries at the university were often delayed, and in some cases even unpaid. Professors started to look back in anger at the ambitious builder of the previous decades. They whispered in the shadows, grumbled in the corridors, and increasingly brought their discontent out into the open.

All these issues, still unresolved, were soon to explode. They would also be transferred onto a new battleground, where they would rage with even greater ferocity. In the midst of the chaos, Olaus Verelius, a colleague and an expert on the Vikings, came with a request: he wanted Rudbeck to draw a couple of maps of ancient Sweden to accompany his forthcoming edition of a Norse saga. As Rudbeck set out to help his friend, he found something that dramatically changed his life.

3

REMARKABLE CORRESPONDENCES

—FYODOR DOSTOYEVSKI,