The historian Correlli Barnett (

Matthew Hervey and the 6th Light Dragoons knew about noise far away: they had heard it well enough in India. But they also knew there could be noise at home – if not actual war then certainly something as repugnant, for in 1827 the Metropolitan Police Act was still two years off, and the magistrates’ only recourse was to the army when civil disturbance threatened.

There was Ireland too, restive in its condition of exploitative poverty and discriminatory legislation. Britons were divided over the Catholic question – giving Catholics the vote and removing the obstacles to holding public office – ‘Catholic Emancipation’. There were no riots against Emancipation yet, as there had been the century before; but there was suspicion, and the authorities had no certain idea where it would lead. There was, indeed, ‘noise’ enough to disturb a good night’s sleep from time to time, if not so much as to keep the country awake for too long.

So Matthew Hervey, thirty-six years old, and in the midst of that glorious metamorphosis from a regimental to a commanding officer, finds himself in noisy circumstances once again. And, naturally, he meets those who would put fingers in their ears rather than deal with the noise. For this is an age when change, change in the army, is regarded as unnecessary, perhaps even injurious to those regimental qualities that had assured victory at Waterloo: discipline, personal bravery and boldness in combat.

Meanwhile, in Prussia, a major general not very much older than Hervey – Carl von Clausewitz – who had fought the French that day in 1815, is putting the final touches to his penetrating study of war and its practice, so that if a Prussian army were again required to do its Kaiser’s will it would do so with absolute efficiency. And at the other end of the technological spectrum, in southern Africa, an instinctive soldier, Shaka, King of the Zulu, is consolidating his astonishing military successes; for in truth Shaka and Clausewitz speak the same military language.

It is these old questions and new threats that Matthew Hervey and the 6th Light Dragoons face, and whose new lessons and old truths they will have to learn and re-learn – painfully.

Rebuke the company of spearmen…

scatter thou the people that delight in war.

PSALM 68

PART I

PATHS OF GLORY

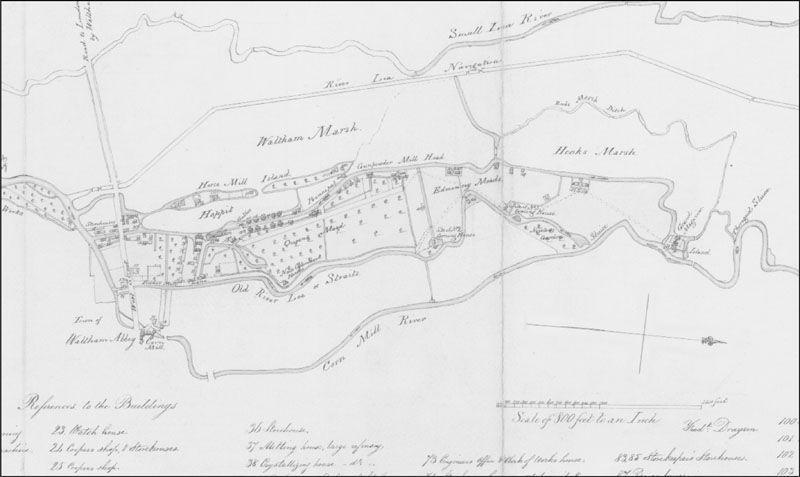

Plan of the Royal Gunpowder Manufactory at Waltham Abbey in 1830 by Frederick Drayson from his

I

MANOEUVRES

Acting-Major Matthew Hervey nodded to the adjutant, and in as many seconds only as it took for him, the officer in temporary command of the 6th Light Dragoons, to rein round to face front again, the first section of the Chestnut Troop discharged a thunderous salvo. Gilbert, his battle-charger, and at rising fifteen years a seasoned campaigner, threw up his head but did not move a foot. Hervey let out the reins a little so that the iron grey gelding could play with the bit as reward.

He looked over his left shoulder, then his right. The lines were ragged. Troop horses had leapt forward, some had run back, others had reared and turned. Barely half the regiment stood as they had been dressed. Even his trumpeter’s grey, a mare which should have known better, was showing a flank and bucking hard, determined to unseat her rider.

Hervey nodded again, the adjutant raised his arm, and the Chestnuts’ second section fired. As the smoke cleared, he could see the first section’s men standing ready, guns reloaded, and second section’s beginning the thirty fevered seconds of swabbing, ramming and tamping before the number one could shout ‘On!’ to tell his section officer that the gun was shotted and re-laid on its target.

Except that there was no shot or target. The Chestnut (more properly the

Number one gun fired, and the remaining rooks in the distant elms took flight, so that Hervey imagined there was not a bird perched on any branch on Hounslow Heath.

‘Rugged elms,’ he mused. He liked elms. As a boy he had climbed them, about the churchyard in Horningsham, to test his courage or to see what the tall nests held. Or sometimes on the plain to gain a distant prospect. He loved the elm-lined lanes in high summer, dark leafy tunnels where he might catch sight of a roe deer at midday – still, secret places, a foreign land, far from the safe parsonage and yet within sound of the church bell. There were no elms in foreign lands, though. Or if there were, they were poor specimens: he had seen none he could recall in France, or Belgium, none in the forests of the east – India, Ava – and certainly not in Spain and Portugal. Yet there