Siri L. Mitchell

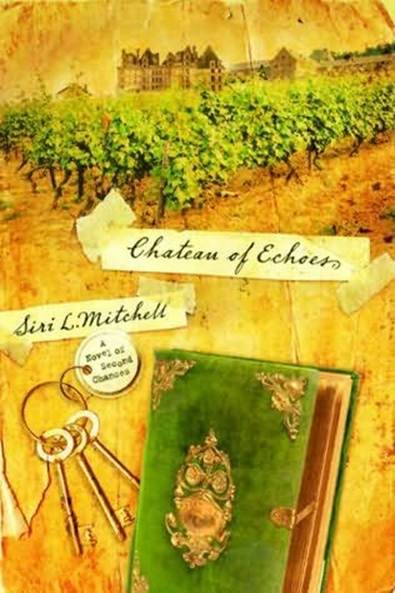

Chateau of Echoes

Copyright © 2005, 2011 Siri L. Mitchell

1

It was a glorious summer day for Brittany, France. The temperature was hovering around 75, and the clouds thinned to let the sun through now and then. That made it warm enough to slip a cornflower blue halter over my black capris. A breeze fingered my hair and tipped my straw gardening hat over my right eye. I am blonde but not in a striking sort of way. I belong to the shade rather than the sunlight, being pale and having eyes the iciest shade of blue.

I paused at the mailbox, clamping the letter between my upper arm and my body, put a hand to the brim of my hat, and played tug-of-war with the breeze to tie the strings of my hat more tightly underneath my chin. As I walked from the mailbox up the mile-long pea-gravel drive toward the chateau I call my home, I relished the crunch of the stones beneath my feet, welding me to the present.

The chateau, which dates from the fourteenth century, has four turrets. It definitely isn’t the biggest in France, and it isn’t the most beautiful, but it is mine. And looking at it as the sun filtered through the clouds, drenching it in a golden haze, I felt an unreasonable sort of pride. The chateau had existed over half a millennium without me, and it would probably exist another half after me. I was only borrowing it during the brief period of my existence. But for that short moment, it belonged to me.

Friends expected that I would be lonely, learning to live alone again in a huge chateau, but it was here that I began to reorder my life. To carve out a space for myself in the world. It had never felt too big or too empty.

It used to be just perfect.

But that morning, I had been working in my potager garden and had the familiar feeling of not being alone. Of a gentle tapping in my heart. And as I sometimes do, when I feel offended by the monolith of a God who refuses to stay away from me, I said out loud, “Would you leave?” And, as usual, I felt an emptying in the air around me.

More and more, I had found myself talking to a God that I didn’t want to acknowledge. A God I didn’t know I believed in anymore. I wished I could be as sure as Peter, my late husband, that God didn’t exist. But I wasn’t, even though I’d effectively bet Peter’s life on those atheist beliefs. But if God did exist, then where did that leave Peter? And what kind of person did that make me?

It was just easier to ignore God. So I did.

After walking past the two square stone pillars that separate the chateau from the grounds, I stopped, surveying the gravel drive and the barren courtyard that lay in front of me. I meant to convert the gravel into a formal garden. Someday-after I’d renovated the stables and taken care of other more immediate improvements. I wanted to channel the driveway into a defined loop and turn the enclosed expanse into a Daedalus labyrinth of cotton, lavender, and yew. Or maybe a knotwork design in a combination of privet, yew, and box. I tried to imagine what the enclosure would look like, shrouded with green geometric patterns of clipped hedges.

I had compiled a collection of books on historical landscaping and had spent many pleasant hours flipping through them, accumulating ideas. I just didn’t know yet what I wanted. But for the moment, it was fine. It looked like 90 percent of the other chateaux in France.

I walked on, kicking up dust from the gravel. Then I scaled the steps of the chateau and swung the massive oak door shut with a kick from my foot. I slipped out of my shoes, took off my hat, and set it beside a vase of flowers on a round table in the vaulted entry hall. The flowers were bunched too tightly, so I stopped to pluck and poke at them. Their purples, pinks, and yellows lightened the mood of the heavy stone walls.

There are three narrow arches leading from this hall. The one on the left provides access to a tightly wound staircase that both descends to the kitchen and allows access to the three floors above. The one in the middle leads to a hallway with another, more generously proportioned, spiral staircase and, past it, the reception hall. From the reception hall, the dining hall can be seen to the left and the council room to the right.

The archway to the right descends to the cellar.

Opening the letter, I walked through the central archway and then sat on a settee in the reception hall. The wavy leaded panes of clear glass set into the thick stone walls diffused the light, and the rectangles of colored glass along the tops of the windows made puddles of color on the black and white tiled floor. I like this room. It’s not meant for use, but rather as a stopping place on the way to a meal or a gathering area for people to meet up before embarking on their day’s business. There are several settees, a

Sliding the letter from the envelope, I admired the heavy, expensive cream paper on which it was written and the assertive slant of the handwriting. It contained a request from an author to rent a room from me for a period of six months. I recognized the name, Robert Cranwell, even after having lived in France for nine years.

Apparently, he’d had the ingenious idea to write a novel that would be loosely based on the life of Alix de Montot,

I couldn’t help but roll my eyes when I read that line.

Alix de Montot.

Had I known the trouble she would cause, I would have burned her journals the day I’d found them. For a fifteenth-century waif, she’d caused a disproportionate amount of chaos in my life.

I’d found her journals in an old trunk in the

In any case, I tried to pull the door up to see exactly what it guarded. I was surprised the wood hadn’t rotted, as the building’s roof had fallen through decades before. The planks forming the door had to have been a good four inches thick, and the hinges and ringed door pull, though rusted, were equally as sturdy. It was the rust that kept me out that first day.

But the next day I was back, armed with a spray can of heavy-duty oven cleaner. I had learned all sorts of tricks as I renovated the chateau’s kitchen. For that room, at least, I’d trusted no one but myself. The oven cleaner