Dalgarno’s method was another way to get a mathematics of language. No need to determine a universe of categories and distinguishing features—you simply decide what the primitives are (no need to systematically break everything down; just ask yourself what makes sense) and assume everything else can be described by adding those primitives together to make a compound. For Dalgarno, “coal” is “mineral black fire,” “diamond” is “precious stone hard,” and “ash tree” is “very fruitless tree long kernel.”

Wilkins thought this method lacked rigor. Dalgarno hadn’t chosen his basic concepts in a principled way, and, worse, the words in his language told you nothing about their meanings, just their arbitrary placement in a nonsense verse. Wilkins was convinced that the ordered tables were necessary. He wanted words to reflect the nature of things—only in this way could the language serve as an instrument for the spread of knowledge and reason. Dalgarno thought the tables were unnecessary. He wanted words to be easy to memorize—only in this way could the language be a useful communication tool. After about a year of arguing, they parted ways, and Wilkins began to work on his own project.

The Word for “Shit”

The problem with natural languages, as Wilkins saw it, was that words tell you nothing about the things they refer to. You must simply learn that a dog is a “dog” in English or a

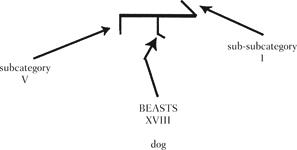

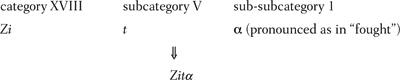

In Wilkins’s system, the word for “dog” does tell you what a dog is. Like Dalgarno, Wilkins worked out a way to refer to a specific position in his tables with a character or a word. Since the concept dog is located in category XVIII (Beasts), subcategory V (oblong-headed), sub-subcategory 1 (bigger kind) (refer to figure 5.3), the character for “dog” would be formed with the symbol for category XVIII, along with modifications indicating subcategory V, and sub-subcategory 1.

The character for “wolf,” being paired with “dog” on the basis of a minimal opposition (docile versus not docile), requires an additional marking for opposite.

Wilkins’s scheme for forming pronounceable words follows the same plan. “Dog” is

and “wolf” is

The words of both Dalgarno’s and Wilkins’s systems direct you to a position in a table, but only in Wilkins’s case does that position mean something. Dalgarno’s word for “light,”

A word in Wilkins’s language doesn’t

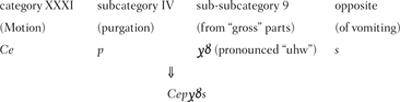

Figure 6.1: Category XXXI (Motion), subcategory IV (Purgation)

Sexual matters being a bit above my level of dictionary maturity, I continued my search in the next category, number XXXI, “Motion.” After skimming past the first three subcategories (animal progression, modes of going, and motions of the parts), which rather haphazardly encompassed everything from “swimming” to “ambling” to “yawning,” I came to subcategory IV, purgation, where I found: “Those kinds of Actions whereby several animals do cast off such excremetitious parts as are offensive to nature.” This was a seven-year-old boy’s dream catalog of bodily function, and it bears reproducing in its entirety (see figure 6.1).

What a window on the past! How interesting to note that people once talked of “breaking wind upwards,” or that you could just as well “neeze” as sneeze. How much less distant three hundred years ago seems when one realizes that then, too, people said “snot” and “puke.” And there it was, not just “shiting,” but a fascinating array of alternatives, which, being the scholar that I am (immaturity notwithstanding), sent me to the

“Muting,” for example, is a special word for “bird poop.” And “sir-reverence” used to mean “with all due respect” (from the Latin

Once I had located my target concept in the tables, I could finally piece together the word for it:

Knowing What You Mean to Say

Even though Wilkins’s universe was supposed to be a more organized, rational place than the one I was living in, I sometimes found it disorienting. Animals could be categorized according to the shapes of their heads, their eating preferences, or their general dispositions. I didn’t really understand why emotions were classified as simple (hope) or mixed (shame), or why tactile sensations could be active (coldness) or passive (clamminess). Entertaining was a bodily action, but shitting was a motion—so was playing dice. While things as different as irony and semicolon were grouped together (under discourse > elements), things as similar as milk and butter were placed miles apart (milk with the other bodily fluids in “Parts, General,” and butter with other foodstuffs in “Provisions”).