unusual for a French submarine to make that journey. Also, that sea is extremely deep in places.”

“And we also have the element of motive in our favor,” said Savary. “We are great friends with Saudi Arabia. And why would anyone, in their right mind, want to blow up the oil system that keeps not only us but most of the civilized world in business? No one would suspect us. No one.”

“I have no doubt the President of France considered that most carefully before he asked us to conduct this feasibility test.”

“Do you think the whole operation could be carried out using cruise missiles alone?”

The General frowned. “I cannot say, but my instinct is no. We certainly could hit the refineries and the pumping stations, because pinpoint accuracy is not a requirement. But the loading platforms and offshore rigs would require real accuracy, and I don’t think we could count on a cruise to hit such a small target in exactly the right place. And anyway, someone working on the rig might see a wayward cruise come in. They’re supposed to be accurate to ten meters. But that’s too big a margin if you’re trying to hit the upper deck of a drilling rig. Better to attack from below the surface.”

Gaston Savary could see why Michel Jobert had been made a general, and he could most certainly see how he came to spearhead the French Army’s Special Forces.

“Well, General,” he said. “I think we must agree it is the most interesting plan. Because if it succeeds, the new King of Saudi Arabia will owe us

“Well, no, he could not,” replied Michel Jobert. “And that would mean French companies would undertake the entire rebuilding program. There would be huge contracts awarded to us, just as the Americans claimed almost all the rebuilding contracts for Iraq.”

“And there’d be a lot of very grateful French industries,” said Savary. “And the riches for the oil industry would be incalculable. Imagine owning the sole marketing agency for all Saudi Arabian oil.

“And I would not be surprised if that led to a long and comfortable retirement for both of us,” said the General. “But for now, let’s not get too excited. I would like to call Admiral Pires over for a half hour.”

“I don’t believe I know him.”

“He’s COMFUSCO.”

“Who the hell’s COMFUSCO?”

“Commandement des Fusiliers Marines Commandos. It’s the French Navy’s special ops outfit. Admiral Pires is the head of it. But he’s an ex-submariner. And right now he is in overall command of all naval assault commandos, plus the Commando Hubert divers unit and the Close Quarters Combat Group — that’s naval counterterrorist — both assigned to COS.”

“That’s every kind of assault from the sea, correct?”

“

“Of course,” said Savary, who was always amazed by the military’s detailed, meticulous operational structures.

General Jobert ordered coffee for three, and a young Army Lieutenant pushed open the door to announce that the Admiral would be there in ten minutes.

Gaston Savary privately thought the entire scheme was a boundless exercise in naked ambition that would probably end up being abandoned. As a kind of super-policeman, he was used to bureaucrats conducting relentless searches, desperately trying to find reasons not to do things. And if ever there was an opportunity to say no, this was surely it. Offhand he could think of about ten reasons himself.

But, like many of his fellow spies and spy masters, Savary was an adventurer at heart. And he knew how to work the system. No one had asked him to blow up the oil fields. He had merely been requested to find out if it was possible to do so without getting caught. And he was most certainly doing that.

Admiral Pires arrived on time, with the flourish of a man who had better things to do than talk to Secret Service agents. Six minutes later, having received a sharply worded briefing from General Jobert, he was reduced to utter silence.

Savary gave him the benefit of his own wisdom. “Admiral,” he said, “we are not being asked to blow up half of Saudi Arabia. We are merely being asked to decide whether it can be done, in secret…to the inestimable advantage of France.”

“Well, technically we could put one of our new SSNs into the Gulf, making an underwater entry through the Strait of Hormuz. It’s deep enough, and it’s been done before.”

“Is that one of the old Rubis-class boats?” asked Savary.

“No. No. This is one of the new Project Barracuda boats we have been building in Cherbourg for several years. You may have read about them. We have just two that will become operational this year. They’re bigger than the old Rubis, around 4,000 tons, nuclear hunter-killers with torpedo and cruise missile capabilities. They actually carry ten MBDA SCALP naval missiles. That’s a derivative of the old Storm/Shadows. They’re good, quiet ships with very good missiles. We’re conducting sea trials right now, off the Brest navy yards.”

“What would you consider the likelihood of getting in and out of the Gulf undetected?” asked the General.

“Oh, very good. And the missiles are all pre-programmed. Yes. I suppose we could launch them at a given target along the Saudi coast.”

“Would anyone see them in flight?”

“Most unlikely. The Saudis are quite sophisticated. But I’d be very surprised if they picked up low-flying missiles like these on radar. They would not be expecting such an attack.”

“Certainly not from their next king,” said Savary, helpfully.

“Any thoughts on operations on the other coast?”

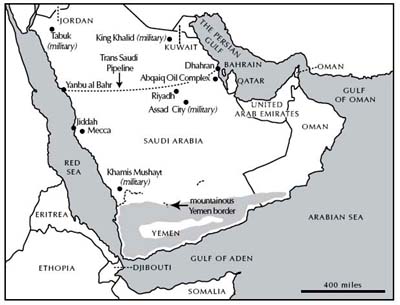

“The Red Sea?” said the Admiral. “Well, that is more difficult, because you’d come through the Suez Canal on the surface. But I don’t think that would attract undue attention. And you might manage to exit the southern end, off Djibouti, at periscope depth; assuming you wanted to stay out of sight. That’s the Bab el Mandeb, the narrow straits that lead out into the Gulf of Aden — shallow, sometimes under 100 meters deep.

“Anyway, a half-submerged submarine might look a bit suspicious to the American radar,

Gaston Savary really liked this suave and knowledgeable Admiral, who looked extremely young to hold such a high office and rank. But he was not young in thought, and he had grasped the significance of the problem very swiftly, as indeed had General Jobert.

“I should of course like to speak to Admiral Romanet first,” said Georges Pires, looking at Savary. “He’s our Flag Officer Submarines in Brest. And I don’t want to second-guess him. But I would say we could hit our missile targets on both coasts from submerged SSNs. And, certainly, in my own area of operations, we could send in teams of commandos to take out the loading platforms and offshore rigs…the Saudi Navy has never been up to much. They’d be no trouble whatsoever.”

The Admiral paused, looked thoughtful. Then he said, “Those platforms are big constructions though. We’d probably need a mix of RDX (research-developed explosive), TNT, and aluminum. And the frogmen would have to swim in with twenty-five-kilogram watertight satchels. And we’d use timers, so the swimmers and perhaps an SDV and the submarine, could get clear before the blast. But we could do it. Most certainly we could do it.”

Admiral Pires again paused. And then he added, “But the Navy’s role is only the beginning, correct? And so I will leave you, while I confer with Admiral Romanet.”

“I’d prefer you bring him here,” said General Jobert. “I think at this early stage, while we are just