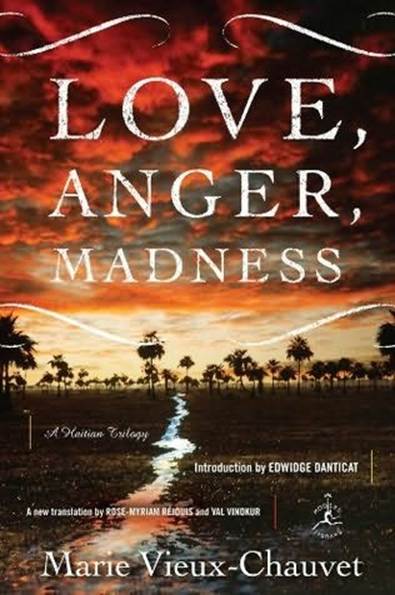

Marie Vieux-Chauvet

Love, Anger, Madness

© 2009

INTRODUCTION

Fewer than a handful of Haitian writers have, both while alive and dead, inspired as much adulation, analysis, and discussion as Marie Vieux-Chauvet. In fact the small number in question constitutes a multigenerational triad of which Marie Vieux-Chauvet was the final survivor and the only female. Jacques Roumain, the grandfather, was the world traveler who returned home to write

Born in Port-au-Prince, the Haitian capital, on September 16, 1916, Marie Vieux-Chauvet was a member of the “occupation generation,” that is, she was born a year after the United States invaded Haiti, launching an occupation that would last nineteen years. The U.S. invasion came in the wake of President Woodrow Wilson’s professed commitment to make the world safe for democracy. However, as soon as the marines landed in Haiti, Wilson’s administration shut down the press, took charge of Haiti’s banks and customs, and instituted a system of compulsory labor for poor Haitians. By the end of the occupation, more than fifteen thousand Haitians had lost their lives. A Haitian gendarmerie was trained to replace the American marines, then proceeded to form juntas, organize coups, and terrorize Haitians for decades. Although American troops were officially withdrawn from Haiti in 1934, the U.S. government maintained economic control of the country until 1947.

“The United States is at war with Haiti,” the American intellectual and activist W.E.B. Du Bois wrote after returning from a fact-finding mission to occupied Haiti. “Congress has never sanctioned the war. Josephus Daniels (President Woodrow Wilson’s Secretary of the Navy) has illegally and unjustly occupied a free foreign land and murdered its inhabitants by the thousands. He has deposed its officials and dispersed its legally elected representatives. He is carrying on a reign of terror, brow-beating, and cruelty, at the hands of southern white naval officers and marines. For more than a year this red-handed deviltry has proceeded, and today the Island is in open rebellion.”

Growing up in the shadow of that rebellion, Marie Vieux-Chauvet, the daughter of a Haitian senator and a Jewish emigre from the Virgin Islands, would later use the turmoil of that period as back-story for

“We have been practicing at cutting each other’s throats since Independence,” she writes of the country that we Haitians like to remind the world was the first black republic in the Western Hemisphere, home to the only slave revolt that succeeded in producing a nation. What we would rather not say, and what Claire Clamont and Marie Vieux-Chauvet are brave enough to say, is that this same country has continued to fail at reaching its full potential, in part because of foreign interference and domination, but also because of internal strife and power struggles. What at first seem like personal dramas in this book become microcosms of larger historical conflicts. In fact, the man Claire and her sisters are all pining after is French. However, the man who terrorizes them is a Haitian, who is given by an unseen dictator the power to decide who lives and dies in X, the pseudonymous town that could stand in for many Haitian towns.

It would be too simple, however, for X and its inhabitants to be plagued by a single terror. Not only are the hills and mountains heartbreakingly eroded but American ships routinely leave X’s ports filled with the prized wood that is causing that erosion. Children die of typhoid and malaria. Beggars drink dirty water from ditches and are routinely persecuted by the ruling colonel, who equally punishes the poor, the artists and intellectuals, as well as the aristocracy, to which Claire and her family belong. Even though this section of the trilogy is mostly set in 1939, five years after the end of the American occupation, it is obvious that it is meant to evoke 1967, the year the book was written, a time when what would end up as a thirty-year dictatorship run by Francois “Papa Doc” Duvalier and Jean-Claude “Baby Doc” Duvalier was becoming more and more severe, enrolling the poor as henchmen and - women, killing them to reduce their number, and persecuting intellectuals for their ideas and artists for their creations. That Marie Vieux-Chauvet ended up in exile in the United States in 1968 after a valiant battle to publish this book in France (see Translator’s Preface) is no surprise. This book, in three distinct, well-developed, nondidactic, masterfully crafted novellas, still manages to condemn totalitarianism and tyranny at every turn. Marie Vieux-Chauvet might as well have been speaking to Haiti’s dictators and many of her future critics when she has Claire write in her journal: “Feel free to shriek at the top of your lungs if you ever see this manuscript; call me indecent, immoral.” But she is neither indecent nor immoral, offering us not just prurient evil in all its vivid ugliness or good in all its beatific triumph, but the murkier and grayer areas in between. How do those who stuff hot potatoes in their child servants’ mouths fare against those who murder a poet or rape a neighbor? How can those who have been brutally enslaved turn around and enslave others? In depicting the many layers of injustice that Haiti-one might even say the world-has never been able to fully shake, Marie Vieux-Chauvet almost seems to be speaking to us about current political issues from the grave. In

“Alone again,” Marie Vieux-Chauvet writes, referring to the young man’s aunt Rose, “she had invented touchingly naive myths to console herself: a leaf whirling in the wind, a butterfly whether black or alive with color, the hooting of an owl or the graceful song of a nightingale seemed pregnant with meaning.”

It is in