at Civitavecchia, thirty miles north of Rome. “A combined sea and air landing would have taken the Italian capital inside seventy-two hours.” That would have brought all Italy south of Rome into Allied hands.

Despite Allied command of the sea, Eisenhower dared nothing so bold as a strike at Rome, because it was beyond the reach of fighter aircraft. He also ignored recommendations that the Allies land on the heel of Italy, around Taranto and Brindisi, also beyond fighter cover, but where the Germans had no troops.

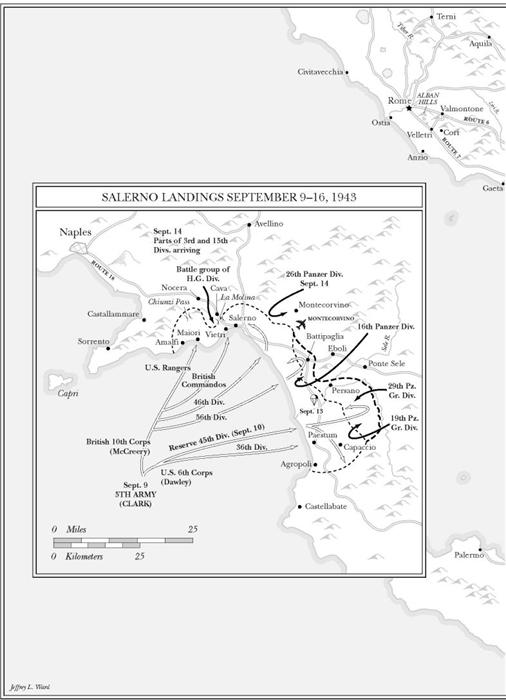

Instead, Eisenhower and Alexander ordered the main thrust by General Mark Clark’s 5th Army around Salerno (Operation Avalanche) on September 9, 1943—55,000 troops in the initial landing, 115,000 more to follow.

Belatedly realizing that no Germans were anywhere close to Taranto, the Allies pulled the British 1st Airborne Division out of rest camps in Tunisia, piled the men onto warships (the only vessels now available), and hurried them to the port—with only six jeeps and no tanks, artillery, or heavy weapons. The “paras” met no resistance, but were unable to exploit their success.

Kesselring, confident the Allies would do nothing daring, concentrated his slender forces around Salerno. Vietinghoff sent just two infantry battalions to slow Montgomery’s entire 8th Army in its step-by-step march up the toe of Italy from the Strait of Messina. Only two roads ran up the toe, one on either side of the mountainous backbone of the peninsula, and they were easily blocked.

Of 10th Army’s six divisions, four had escaped from Sicily and were badly depleted in men and equipment. Vietinghoff sent the 15th Panzergrenadier and Hermann Goring Divisions to Naples to refit, the 1st Parachute Division to the east coast to defend Foggia, and the 29th Panzergrenadier Division around the toe of Italy to face Montgomery. His other two divisions were the 16th and 26th Panzer. But the 26th had no tanks and Vietinghoff sent it temporarily to block 8th Army. This left the 16th Panzer, his best force, but with only half the strength of an Allied armored division, possessing eighty Mark IV tanks and forty self-propelled assault guns. He placed it to cover the Gulf of Salerno.

The landing was made by the U.S. 6th Corps under Ernest J. (Mike) Dawley on the right, and the British 10th Corps under Sir Richard L. McCreery on the left.

McCreery’s corps landed on a seven-mile stretch of beaches just south of Salerno near the main road (Route 18) to Naples. This road crossed the low Cava Gap. Capture of that gap was important to open a way to Naples and to block German reinforcements coming from the north.

In 10th Corps were the British 46th and 56th Infantry Divisions, two British Commando outfits, and three battalions of American Rangers. The Commandos and Rangers were to seize Cava Gap and Chiunzi pass on a neighboring route.

Dawley’s corps struck the beaches twenty to twenty-five miles south of Salerno around the Sele River and Paestum. The untried U.S. 36th Infantry Division was to land, with the U.S. 45th Infantry Division in reserve.

The Allies knew the Germans were expecting the invasion at Salerno because a German radio commentator forecast it two weeks before it took place. Even so, General Clark counted on catching the Germans unawares and forbade any preliminary naval bombardment, though the naval commander, American Vice Admiral H. Kent Hewitt, said, “It was fantastic to assume we could obtain tactical surprise.”

The landing craft reached the British beach with little loss because McCreery, despite Clark’s order, authorized a short but intense bombardment of beach defenses by naval guns and rockets (modeled on the German

In the 10th Corps sector, American Rangers secured the Chiunzi pass within three hours, but German defenders stopped Commandos trying to grab the Cava Gap.

The main British landings south of Salerno met heavy resistance from the beginning and failed to secure the first-day objectives: Salerno harbor, Montecorvino airfield ten miles east of Salerno, and the road junctions at Battipaglia and Eboli, thirteen and sixteen miles east of the town.

When 36th Division troops hit their beaches, they encountered even heavier curtains of fire, plus numerous German air attacks that struck the men as they were on shore and coming on shore. The Americans got good gunfire support from destroyers that moved in close, and it checked thrusts by German tanks. By nightfall the American left wing had pushed about five miles inland to Capaccio, but the right wing was still pinned down near the beaches.

September 10 was quiet for the Americans, for 16th Panzer Division moved to confront 10th Corps, a greater strategic menace. The Americans expanded their bridgehead and landed most of 45th Division.

Meanwhile the British 56th Division captured Montecorvino airfield and Battipaglia, but was driven back by a counterattack of two German battalions and some tanks. That night the division mounted a three-brigade attack to capture the heights of Mount Eboli, but got nowhere. The 46th Division occupied Salerno, but did not press northward.

In the American sector, 45th Division advanced ten miles inland up the east bank of the Sele River, but a counterattack by a single German battalion and eight tanks threw it back.

By the end of the third day the Allies, now with the equivalent of four divisions on the ground, still held only two shallow bridgeheads, while the Germans possessed the heights and the approach roads.

By now 29th Panzergrenadier Division had arrived, plus a battle group of two battalions and twenty tanks from the Hermann Goring Division. On September 12, 29th Panzergrenadier with part of 16th Panzer thrust between the British and Americans and drove the British out of Battipaglia. The next day, the Germans evicted the Americans from Persano, forcing a general withdrawal. In some places German armored vehicles reached within half a mile of the beach. On the same day the Hermann Goring

By the evening of September 13 the situation was so grim that Clark stopped unloading supply ships, and prepared to reembark 5th Army headquarters, while asking that all available craft be made ready to evacuate 6th Corps. The order produced consternation at Allied headquarters and brought immediate help. Matthew Ridgway, commander of 82nd Airborne Division, dropped paratroops on the American sector that evening. On September 14, Eisenhower sent all available aircraft to attack German positions and their communications, a total of 1,900 sorties in one day. At the same time, warships commenced a powerful bombardment, hitting every target they could locate. The British 7th Armored Division started landing on the British bridgehead on September 15.

There was a lull on September 15 as the Germans reorganized their bombed and shelled units, and brought up some reinforcements, including the still-tankless 26th Panzer Division, and parts of the 3rd and 15th Panzergrenadier Divisions. Total German strength was only four divisions and a hundred tanks, however, while Clark had on shore on September 16 seven larger divisions and 200 tanks.

The same day the British battleships

September 16 was eventful in another way: Montgomery’s 8th Army made contact in a fashion with Clark’s 5th Army. A group of war correspondents got so exasperated with Montgomery’s snail-like pace up the peninsula that they struck out on their own on minor roads and reached 5th Army across the fifty-mile stretch without meeting any Germans.

On the same day the Germans launched a renewed effort to drive the Allied bridgeheads into the sea. Combined artillery and naval gunfire, plus tanks, stopped the assaults, and Kesselring, seeing how close Montgomery was to 5th Army, authorized disengagement on the coastal front and gradual retreat northward.

First stage was withdrawal to the Volturno River, twenty miles north of Naples. As the Germans pulled away, a bomber disabled the

Kesselring withdrew because 8th Army could move east of Salerno, and easily outflank the German positions, since Vietinghoff had only a small fraction of the combined forces of 5th and 8th Armies. Indeed, the Allies could have completely dislodged the German position in southern Italy by a swift strike up the east coast beyond Foggia to Pescara, where the main trans-peninsula road led to Rome.