“I do not want to surprise you,” said Leo, “but, as a matter of course, I keep my boots on in public places and there is no need then for anyone to smell my socks or my feet.”

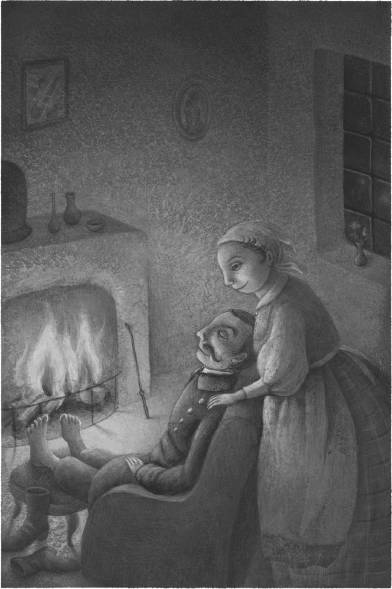

Gloria came up behind Leo and put her hands on his shoulders. She bent and kissed the top of his head. “What are you thinking?” she said.

“I am imagining Peter,” said Leo Matienne, “and how happy he was to learn that he could see the elephant for himself. His face lit up in a way that I have never seen.”

“It is wrong about that boy,” said Gloria. She sighed. “He is kept a prisoner up there by that man, whatever he is called.”

“He is called Lutz,” said Leo. “His name is Vilna Lutz.”

“All day it is nothing but drilling and marching and more marching. I hear them, you know. It is a terrible sound, terrible.”

Leo Matienne shook his head. “It is a terrible thing altogether. He is a gentle boy and not really cut out for soldiering, I do not think. There is a lot of love in him, a lot of love in his heart.”

“Most certainly there is,” said Gloria.

“And he is up there with no one and nothing to love. It is a bad thing to have love and nowhere to put it.” Leo Matienne sighed. He bent his head back and looked up into his wife’s face and smiled. “And we are all alone down here.”

“Don’t say it,” said Gloria Matienne.

“It is only that—”

“No,” said Gloria. “No.” She put a finger to Leo’s lips. “We have tried and failed. God does not intend for us to have children.”

“Who are we to say what God intends?” said Leo Matienne. He was silent for a long moment. “What if?”

“Don’t you dare,” said Gloria. “My heart has been broken too many times, and it cannot bear to hear your foolish questions.”

But Leo Matienne would not be silenced. “What if?” he whispered to his wife.

“No,” said Gloria.

“Why not?”

“No.”

“Could it be?”

“No,” said Gloria Matienne, “it cannot be.”

Chapter Eight

At the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, in the cavernous dorm room, in her small bed, Adele was dreaming again of the elephant knocking and knocking, but this time Sister Marie was not at her post, and no one at all came to open the door.

Adele awoke and lay quietly and told herself that it was just a dream, only a dream. But every time she closed her eyes, she saw again the elephant, knocking, knocking, knocking, and no one at all answering her knock. And so she threw back the blanket and got out of bed and went down the stairs in the cold and the dark and made her way to the front door. She was relieved to see that there, just as always, just as for ever, sat Sister Marie in her chair, her head bent so far forward that it rested almost on her stomach, her shoulders rising and falling, and a small sound, something very much like a snore, issuing forth from her mouth.

“Sister Marie,” said Adele. She put her hand on the nun’s shoulder.

Sister Marie jumped. “But the door is unlocked!” she shouted. “The door is forever unlocked. You must simply knock!”

“I am inside already,” said Adele.

“Oh,” said Sister Marie, “so you are. So you are. It is you. Adele. How wonderful. Although of course you should not be here. It is the middle of the night. You should be in your bed.”

“I dreamed,” said Adele.

“But how lovely,” said Sister Marie. “And what did you dream of?”

“The elephant.”

“Oh, elephant dreams, yes. I find elephant dreams particularly moving,” said Sister Marie, “and portentous, yes, although I am forced to admit that I myself have yet to dream of an elephant. But I wait and hope. One must wait and hope.”

“The elephant came here and knocked, and there was no one to answer the door,” said Adele.

“But that cannot be,” said Sister Marie. “I am always here.”

“And then, another night, I dreamed that you opened the door and the elephant was there, and she asked for me and you would not let her in.”

“Nonsense,” said Sister Marie. “I turn no one away.”

“You said you could not understand her.”

“I understand how to open a door,” said Sister Marie gently. “I did it for you.”

Adele sat down on the floor next to Sister Marie’s chair. She pulled her knees up to her chest. “What was I like then?” she said. “When I first came here to you.”

“Oh, so small, like a mote of dust. You were only a few hours old. You had just been born, you see.”

“Were you glad?” said Adele. “Were you glad that I came?” She knew the answer. But she asked anyway.

“I will tell you,” said Sister Marie, “that before you arrived, I was sitting here in this chair, alone, and the world was dark, very dark. And then suddenly you were in my arms, and I looked down at you…”

“And you said my name,” said Adele.

“Yes, I spoke your name.”

“And how did you know it? How did you know my name?”

“The midwife said that your mother, before she died, had insisted that you be called Adele. I knew your name, and I spoke it to you.”

“And I smiled,” said Adele.

“Yes,” said Sister Marie. “And suddenly it seemed that there was light everywhere. The world was filled with light.”

Sister Marie’s words settled down over Adele like a warm and familiar blanket, and she closed her eyes. “Do you think,” she said, “that elephants have names?”

“Oh, yes,” said Sister Marie. “All of God’s creatures have names, every last one of them. Of that I am sure; of that I have no doubt at all.”

Sister Marie was right, of course: everyone has a name.

Beggars have names.

Outside the Orphanage of the Sisters of Perpetual Light, in a narrow alley off a narrow street, sat a beggar named Tomas; huddled up close to him, in an effort both to give and to receive warmth, was a large black dog.

If Tomas had ever had a last name, he did not know it. If he had ever had a mother or a father, he did not know that either.

He knew only that he was a beggar.

He knew how to stretch out his hand and ask.

Also he knew, without knowing how he knew, how to sing.

He knew how to construct a song out of the nothing of day-to-day life and how to sing that nothing into a song so beautiful that it could sustain the vision of a whole and better world.

The dog’s name was Iddo.