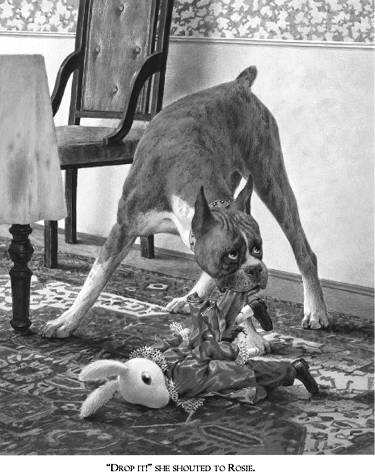

room table, spraying the white tablecloth with urine. He then trotted over and sniffed Edward, and before Edward even had time to consider the implications of being sniffed by a dog, he was in Rosie’s mouth and Rosie was shaking him back and forth vigorously, growling and drooling.

Fortunately, Abilene’s mother walked past the dining room and witnessed Edward’s suffering.

“Drop it!” she shouted to Rosie.

And Rosie, surprised into obedience, did as he was told.

Edward’s silk suit was stained with drool and his head ached for several days afterward, but it was his ego that had suffered the most damage. Abilene’s mother had referred to him as “it,” and she was more outraged at the dog urine on her tablecloth than she was about the indignities that Edward had suffered at the jaws of Rosie.

And then there was the time that a maid, new to the Tulane household and eager to impress her employers with her diligence, came upon Edward sitting on his chair in the dining room.

“What’s this bunny doing here?” she said out loud.

Edward did not care at all for the word

The maid bent over him and looked into his eyes.

“Hmph,” she said. She stood back up. She put her hands on her hips. “I reckon you’re just like every other thing in this house, something needing to be cleaned and dusted.”

And so the maid vacuumed Edward Tulane. She sucked each of his long ears up the vacuum-cleaner hose. She pawed at his clothes and beat his tail. She dusted his face with brutality and efficiency. And in her zeal to clean him, she vacuumed Edward’s gold pocket watch right off his lap. The watch went into the maw of the vacuum cleaner with a distressing

When she was done, she put the dining-room chair back at the table, and uncertain about exactly where Edward belonged, she finally decided to shove him in among the dolls on a shelf in Abilene’s bedroom.

“That’s right,” said the maid. “There you go.”

She left Edward on the shelf at a most awkward and inhuman angle — his nose was actually touching his knees; and he waited there, with the dolls twittering and giggling at him like a flock of demented and unfriendly birds, until Abilene came home from school and found him missing and ran from room to room calling his name.

“Edward!” she shouted. “Edward!”

There was no way, of course, for him to let her know where he was, no way for him to answer her. He could only sit and wait.

When Abilene found him, she held him close, so close that Edward could feel her heart beating, leaping almost out of her chest in its agitation.

“Edward,” she said, “oh, Edward. I love you. I never want you to be away from me.”

The rabbit, too, was experiencing a great emotion. But it was not love. It was annoyance that he had been so mightily inconvenienced, that he had been handled by the maid as cavalierly as an inanimate object — a serving bowl, say, or a teapot. The only satisfaction to be had from the whole affair was that the new maid was dismissed immediately.

Edward’s pocket watch was located later, deep within the bowels of the vacuum cleaner, dented, but still in working condition; it was returned to him by Abilene’s father, who presented it with a mocking bow.

“Sir Edward,” he said. “Your timepiece, I believe?”

The Rosie Affair and the Vacuum-Cleaner Incident — those were the great dramas of Edward’s life until the night of Abilene’s eleventh birthday when, at the dinner table, as the cake was being served, the ship was mentioned.

3

SHE IS CALLED THE

“What about Pellegrina?” said Abilene.

“I will not go,” said Pellegrina. “I will stay.”

Edward, of course, was not listening. He found the talk around the dinner table excruciatingly dull; in fact, he made a point of

“And what about Edward?” she said, her voice high and uncertain.

“What about him, darling?” said her mother.

“Will Edward be sailing on the

“Well, of course, if you wish, although you are getting a little old for such things as china rabbits.”

“Nonsense,” said Abilene’s father jovially. “Who would protect Abilene if Edward was not there?”

From the vantage point of Abilene’s lap, Edward could see the whole table spread out before him in a way that he never could when he was seated in his own chair. He looked upon the glittering array of silverware and glasses and plates. He saw the amused and condescending looks of Abilene’s parents. And then his eyes met Pellegrina’s.

She was looking at him in the way a hawk hanging lazily in the air might study a mouse on the ground. Perhaps the rabbit fur on Edward’s ears and tail, and the whiskers on his nose had some dim memory of being hunted, for a shiver went through him.

“Yes,” said Pellegrina without taking her eyes off Edward, “who would watch over Abilene if the rabbit were not there?”

That night, when Abilene asked, as she did every night, if there would be a story, Pellegrina said, “Tonight, lady, there will be a story.”

Abilene sat up in bed. “I think that Edward needs to sit here with me,” she said, “so that he can hear the story, too.”

“I think that is best,” said Pellegrina. “Yes, I think that the rabbit must hear the story.”

Abilene picked Edward up, sat him next to her in bed, and arranged the covers around him; then she said to Pellegrina, “We are ready now.”

“So,” said Pellegrina. She coughed. “And so. The story begins with a princess.”

“A beautiful princess?” Abilene asked.

“A very beautiful princess.”

“How beautiful?”

“You must listen,” said Pellegrina. “It is all in the story.”

4

ONCE THERE WAS A PRINCESS WHO was very beautiful. She shone as bright as the stars on a moonless night. But what difference did it make that she was beautiful? None. No difference.”

“Why did it make no difference?” asked Abilene.

“Because,” said Pellegrina, “she was a princess who loved no one and cared nothing for love, even though there were many who loved her.”

At this point in her story, Pellegrina stopped and looked right at Edward. She stared deep into his painted-on eyes, and again, Edward felt a shiver go through him.