their moral unscrupulousness. He became the de facto technical head of the conspiracy, and it was his task to lay the groundwork for the government takeover to follow Hitler’s assassination. His removal would provide the much-discussed “initial spark” that would set the rest of the plan in motion.

With Beck, Tresckow, and Olbricht, the opposition at last had the foundation it had lacked for so long. Nevertheless, it was still very loosely organized, it faced enormous risks, and it had to follow many a circuitous path. The various resistance groups were continuing to operate largely on their own, and so, to bring them closer together and to facilitate coordination of their plans, Tresckow asked Schlabrendorff to act as a sort of permanent intermediary between Army Group Center on the one hand and Beck, Goerdeler, Oster, and Olbricht on the other.

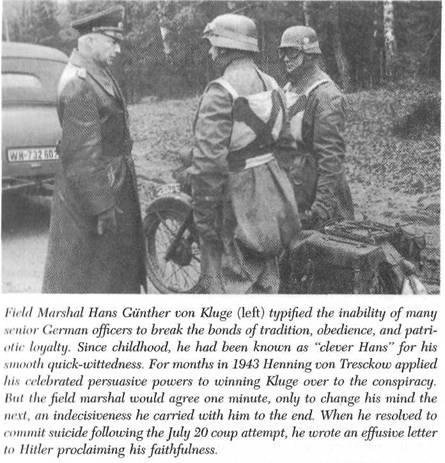

Tresckow also placed high hopes in Kluge, the new commander in chief of Army Group Center. Tresckow’s relationship with Bock had soured for good after the field marshal cut him short during a last attempt to bring him over to the opposition; Bock had replied sharply that he would tolerate no further attacks on the Fuhrer. Initial inquiries showed Kluge to be more alert, concerned, and accessible. He had sufficient insight to realize that Hitler was leading Germany and the Germans straight to catastrophe, and he was morally sensitive enough to be shocked by the crimes of SS and SD units behind the front. Furthermore, he was by no means submissive, occasionally even speaking out against Hitler’s interference in the struggle at the front and his increasingly obvious contempt for the officer corps.

Recognizing that any successful revolt would have to be led by an army group commander or at least by a well-known military figure, Tresckow from the very outset focused all his talent and persuasive powers on winning Kluge over. He ordered his staff to make sure that Kluge saw all negative information: horrifying reports about the Einsatzgruppen, news about fresh enemy units appearing on other parts of the front, and memoranda about the huge capacity of the United States for the production of war materiel. When, on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday, Kluge received a handwritten message from Hitler along with a check for 250,000 marks, Tresckow immediately suggested that he could only justify accepting such an amount in the eyes of posterity by claiming that preparations to overthrow the regime were already under way and he had to avoid raising the slightest suspicion.27

It was not for nothing, however, that Hans Kluge (whose surname means

Tresckow’s first major success was in persuading Kluge to receive Goerdeler in army group headquarters, a significant achievement as Goerdeler had never made any secret of his beliefs and virtually everyone knew why he was so conspicuously on the move at all times. (Once, when General Thomas suggested that the chief of the OKW, Field Marshal Keitel, grant Goerdeler an audience, Keitel replied with horror, “Don’t let the Fuhrer find out you have connections with people like Goerdeler. He’ll eat you up!”29)

Using false papers provided by Oster, Goerdeler arrived at the army group after a daring eight-day journey. His enthusiasm and determination made a strong impression on both Tresckow and Kluge. One officer even claimed to see “the ice break” with the field marshal. In any case, Goerdeler and Kluge held several meetings, apparently considering, among other things, having Hitler arrested when he visited army group headquarters. Before Goerdeler had even had time to return to Berlin, however, Beck received a confidential letter from Kluge complaining that he had been “ambushed” by the visit and that “misunderstandings” may have arisen.30 Kluge’s attitude was succinctly described shortly thereafter by Captain Hermann Kaiser, who kept the reserve army war diaries and wrote in his own journal: “First, no participation in any Operation Fiesco. Second, no action against Pollux [Hitler]. Third, will not stand in the way when an action begins.”31

By the fall of 1942 at the latest Tresckow had resolved nevertheless to stage an attack on the regime from Army Group Center. Apparently he hoped to sweep the vacillating Kluge along when the time came. Their conversations had convinced him that it was imperative not only to arrest Hitler but to kill him. Like Bock before him, Kluge always reverted to the oath of loyalty he had sworn; even Tresckow had had some difficulty in finding his way out of the maze of scruples. Patriotic and religious motives finally helped him and many of his colleagues in the military resistance to overcome those feelings. Hitler, Tresckow concluded, was not only the “destroyer of his own country” but also the “source of all evil.” Nevertheless, the issue continued to haunt Tresckow, and his insistence to the very last (he killed himself on the eastern front on July 21, 1944) that “we aren’t really criminals” betrays his misgivings.32

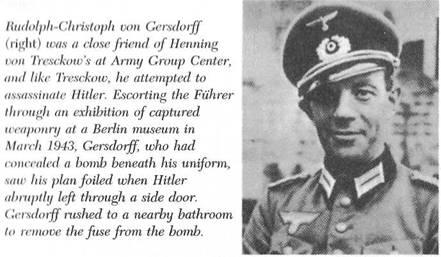

For a time Tresckow apparently entertained the idea of simply taking a pistol to Hitler. He would either do the deed himself or assign a group of his officers to act as an execution squad. According to all indications, he never totally abandoned this plan, which seemed to him the bravest and most chivalrous form of tyrannicide. All the same, by the summer of 1942 he was asking Major Rudolph-Christoph von Gersdorff to procure a “particularly powerful explosive” and “a totally reliable, completely silent fuse.” Although Gersdorff had to sign receipts each time he took possession of such materials, he was eventually able to accumulate dozens of different explosives, which he, Tresckow, and Schlabrendorff tested in the meadows along the nearby Dnieper River. Finally they selected a British-made plastic-explosive device about the size of a book with a pencil-shaped detonator.

In late 1942 Olbricht indicated that he still needed about eight weeks to complete preparations for the coup and to have reliable units standing by not only in Berlin but also in Cologne, Munich, and Vienna “when the first step against Hitler is taken from elsewhere.” Shortly thereafter Tresckow traveled to Berlin to clear up the last remaining questions with Olbricht and Goerdeler and, most of all, to emphasize that time was running short. Tresckow’s impatience pervades the notes taken by one of the participants. There was “not a day to lose,” he said. “Action should be taken as quickly as possible. No initial spark can be expected from the field marshals. They’ll only follow an order.”33 Olbricht now gave early March as the target date and explained that Colonel Fritz Jager would advance at the appointed lime with two panzer units to deal with the guard battalion in Berlin. In addition, Captain Ludwig Gehre had assembled a task force for special assignments, and the new Brandenburg division that was being organized in the Berlin area under Colonel Alexander von Pfuhlstein would handle Nazi Party forces. Friedrich Wilhelm Heinz, who commanded the Fourth Regiment of this division, emerged from the shadows to which he had retreated in the fall of 1938. Gisevius was summoned to Berlin to assist Olbricht with the planning, and Witzleben, though seriously ill, agreed with Beck that he would assume supreme command of the Wehrmacht. This basic plan-an assassination attempt followed by seizure of key positions in Berlin and a few other centers-would be largely adopted once again on July 20, 1944.

Getting a bomb near Hitler proved to be far more difficult than originally Imagined, The Fuhrer was growing increasingly distrustful and solitary, he seldom left his headquarters and then often altered his travel plans without warning. Arrangements were made for him to visit Field Marshal Weichs’s army group in Poltava, where a group of officers was also prepared to overpower him; he abruptly changed his route, however, and flew instead to Saporoshe. There, ironically, he barely escaped an attacking Russian tank unit that had run out of fuel at the edge of his landing field.

After turning down a number of requests, Hitler finally agreed to visit Army Group Center in Smolensk in the early morning of March 13, 1943, on his way from his headquarters in Vinnitsa back to Rastenburg. Shortly before the three aircraft carrying the Fuhrer, his staff, and the SS escort touched down, Kluge suddenly sensed some thing and turned to Tresckow, saying, “For heaven’s sake, don’t do anything today! It’s still too soon for that!”34 In fact, Tresckow, believing that the most opportune time had already passed with the battle of Stalingrad that winter, had taken the precaution of developing a number of assassination plans simultaneously. One of them called for a bomb to be placed in Hitler’s parked vehicle during the visit, but all attempts to slip through the phalanx of SS men to reach the car failed. A second plot was to be carried out if