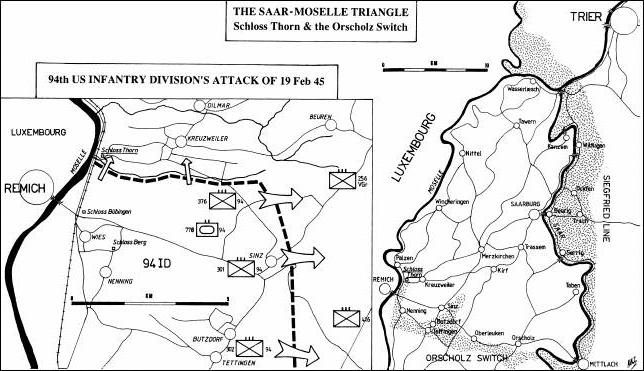

Switch. The day it finally fell, the Americans were engaged in a major operation to clear the high ridge dominating the Switch from east of Sinz.

Towards the end of January, beginning of February 1945, the 256th Volksgrenadier Infantry Division, and with it Regiment 481 to which I belonged, was pulled out of the northern Vosges Mountains. We were all glad to be able to leave that sector. Four weeks of hard infantry combat in the snow and cold lay behind us.

Partly by rail and partly on foot over the Hunsruck Highroad, we reached Irsch, where I met a member of the 11th Panzer Division that we were relieving. The 11th Panzer were required elsewhere urgently. When I replied in some amazement to his query as to how many tanks we had with ‘none at all’, he laughed out aloud. ‘Have fun,’ he called behind him as he made off, ‘you will never be able to hold on to the sector without tanks!’[3]

The sector in question was the so-called Orscholz-Switch, a section of the Siegfried Line between the Moselle and the Saar, that had been fought over for months. It got its name from the little place of Orscholz lying directly opposite the Saar Loop.

From Irsch we marched by night, as one could only march by night because of ground-attack aircraft, down the steep mountain road and across the Saar into Saarburg. Our platoon found accommodation in a building at the entrance to the town nearest the river, where an old man was still holding out, although Saarburg was supposed to have been evacuated. This was the last time we got a skinful.

On the evening of the next day we continued our march. The front was not very far off now with the lightning flashes of guns firing, exploding shells and the usual sounds of the front line. Here and there a fire glowed in the night. At dawn we came to an abandoned, half-destroyed farm. The enemy was firing at night on the roads and crossroads. After the previous day’s drinking bout and the long march, we threw ourselves down anywhere and slept.

Next evening we moved on again. Smoking was strictly forbidden. Toward morning we came upon a well spread-out, destroyed village called Kreuzweiler, where we split up among the cellars. There were big wine cellars with massive, vaulted ceilings. There were also numerous wine casks of various sizes, but all were empty. Our predecessors had made a good job of it. As I later discovered, Kreuzweiler had changed hands several times, as the state of the village showed. My platoon spent the night in a big wine cellar where a guesthouse stands today.

We were a mortar platoon equipped with 80mm mortars. I was the platoon range-finder and so ended up a maid of all work, mainly, however, as a forward observer. I found myself a really good sleeping place in the cellar, sharing a worn-out sofa with two other soldiers. As I was dropping off to sleep, I heard two officers talking and my name was mentioned. I pricked up my ears and discovered that I was to go to Schloss Thorn as a forward observer with Staff Sergeant Witt. I nearly had a fit. Witt was about forty years old, a professional musician who had been conscripted into a Luftwaffe orchestra and gained the rank of staff sergeant with it. Then at the end of September 1944 the orchestra was disbanded and Witt was transferred to combat duty. I had never then or since come across anyone who lived in such a constant state of panic as Staff Sergeant Witt. His escapades in Holland and Haganau were known throughout the division, but that is another story.

From Kreuzweiler a narrow road twisted down toward the valley, made an almost ninety degree turn to the left, then about 150 m further on another similar turn to the right, then went straight on again to meet the road alongside the Moselle (today the B 419). In the angle formed by these bends lay Schloss Thorn, an imposing rectangular building, now, however, totally destroyed. It was not surprising, as this had been the front line for almost five weeks. The road leading from the valley had a small stream running parallel to it on the right that had cut down to about four metres at the deepest part, thickly overgrown but dried out at the moment. The light reverse slope, relatively good cover and road close by, ensured our ammunition resupply.

Several days later two enemy ground-attack aircraft made a low-level attack on Kreuzweiler and strafed our fire position as they flew off. They had apparently not seen our fire position as such, only some soldiers running around. However, we thought that we had been discovered and moved further to the right, where a track led to a small gully nicely concealed by a copse. There our mortars were to perform magnificently.

Neither Witt nor I had anything to do with the first fire position nor the change over to the new one, as we were by this time already in Schloss Thorn. We followed the road to the first sharp turn to the left, where we turned to the right and came across two half-destroyed buildings. We went through a hole in the wall to the right again and along past a long, destroyed building to a big arched gateway (without the gates) through which we came to the castle’s inner courtyard. As the whole area was strongly mined, we had to keep strictly within the denoted paths. As I said, it was a rectangular building with one side to the south and another to the west overlooking the Moselle. There were the remains of a thick tower, the top half of it shot away, and a long connecting building to a more slender tower, still intact, from where I was later to do my observing.

There were also two big cellars, the first used as a toilet, the second, reached by a flight of steps, served as accommodation for about fifteen soldiers. From the latter a passage led to another, smaller cellar, where Witt and I made our home. It had a small stove, for which our predecessors had knocked a hole through the ceiling. There was an artillery forward observer in the big cellar and a heavy machine gun team. The forward observer had two radio operators with him, through whom he had radio contact with his battery. From the big cellar a narrow flight of steps led to a platform with an arrow-slit-like view of the road leading down to the Moselle, and then a few more steps to the long corridor on the ground floor, from which one entered a big corner room with views to the south and to the west over the Moselle to Luxembourg.

We received almost exclusively only cold rations, occasionally also meat, which we had to cook ourselves, about which no one knew anything except Witt. He was an exceptional cook but, because of his permanent anxiety, had no appetite. I still remember him making a delicate goulash, which I stirred endlessly. Normally a cook would be pleased when others praise the food he has prepared, but not Witt. He even once called me a hog.

I spent a lot of time in the narrow tower, from where I had a good view of the destroyed bridge leading across to Remich. There was a small customs house on the German side with an American forward observer in it. When they changed men over, they would have to run about 50m across open ground, which they always did flat out. But my narrow tower required a special skill in climbing it. The spiral staircase leading up had long narrow windows on the enemy side under which one had to crawl on one’s belly, or the Americans would see you and immediately open fire, something which would set Staff Sergeant Witt off into a panic.

For me it was like a holiday. The hard weeks in the Vosges Mountains with deep snow, icy temperatures and hard fighting in the woods, were forgotten. Here at Schloss Thorn we had shellproof accommodation, thanks to the vaulted cellars, and adequate rations. We did no sentry duties, as that was for the infantry, their heavy machine gun being in the big corner room covering the bridge and Nennig. I often chatted with the machine gunners. The No. 1 was a Sergeant Flinn (or Flint), the No. 2 a little chap with the Iron Cross First Class. Our mortar target area ‘Anton’ lay close behind the ridge beyond the road, in what was dead ground for me. My attempts at getting Witt to bring the target area directly on to the road were brusquely rejected.

There were also some incidents. Once an American reconnaissance aircraft, similar to our Fieseler Storch, circled over us and Kreuzweiler. We opened a ferocious fire on him and the lad hastily turned away and was not seen again. Now and then a couple of ground-attack aircraft would come back and strafe Kreuzweiler. Pulling up again they had to pass over Schloss Thorn, and we fired with everything we had. Staff Sergeant Witt threw a fit, saying that we should not provoke them, or the Americans would reply with their heavy artillery. However, nobody took any notice of him any more.

But there was an even better incident to come. One night two men from the Propaganda Company were brought to us, who naturally wanted to see some action. So the infantry had to creep through the rubble with grim expressions and weapons at the ready, jump up and lie down again, and occasionally fire a few bursts with their assault rifles. The shots had to be taken all over again, because one or other of them had grinned at the wrong moment. One of the Propaganda Company men also wanted to film a mortar bomb exploding in no-man’s land, so we climbed up the narrow tower, I going on all fours as usual but not noticing that the Propaganda Company man was walking upright. I gave the order for a salvo on ‘Anton’ and the hits were easily visible in the foreground. The cameramen filmed eagerly away, even turning the cameras on me, but then I heard the incoming fire; ‘Quickly down below! There’s going to be a row!’ I shouted, and we slipped down the spiral staircase, not a moment too