Thomas Cranmer, Cambridge scholar, reforming Archbishop of Canterbury, succeeding Warham.

Hugh Latimer, reforming priest, later Bishop of Worcester.

Rowland Lee, friend of Cromwell, later Bishop of Coventry and Lichfield.

Lord Berners, the Governor, a scholar and translator.

Lord Lisle, the incoming Governor.

Honor, his wife.

William Stafford, attached to the garrison.

Lady Bryan, mother of Francis, in charge of the infant princess, Elizabeth.

Lady Anne Shelton, Anne Boleyn's aunt, in charge of the former princess, Mary.

Eustache Chapuys, career diplomat from Savoy, London ambassador of Emperor Charles V.

Jean de Dinteville, an ambassador from Francis I.

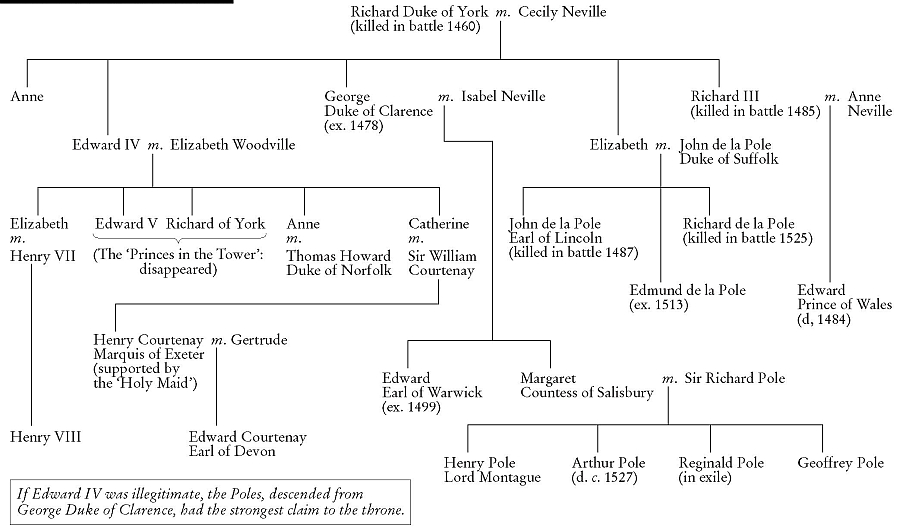

Henry Courtenay, Marquis of Exeter, descended from a daughter of Edward IV.

Gertrude, his wife.

Margaret Pole, Countess of Salisbury, niece of Edward IV.

Lord Montague, her son.

Geoffrey Pole, her son.

Reginald Pole, her son.

Old Sir John, who has an affair with the wife of his eldest son Edward.

Edward Seymour, his son.

Thomas Seymour, his son.

Jane, his daughter: at court.

Lizzie, his daughter, married to the Governor of Jersey.

William Butts, a physician.

Nikolaus Kratzer, an astronomer.

Hans Holbein, an artist.

Sexton, Wolsey's fool.

Elizabeth Barton, a prophetess.

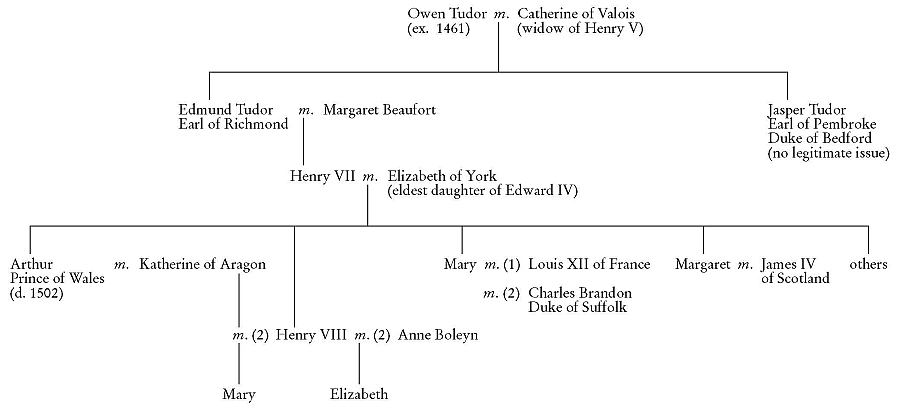

Family Trees

‘There are three kinds of scenes, one called the tragic, second the comic, third the satyric. Their decorations are different and unalike each other in scheme. Tragic scenes are delineated with columns, pediments, statues and other objects suited to kings; comic scenes exhibit private dwellings, with balconies and views representing rows of windows, after the manner of ordinary dwellings; satyric scenes are decorated with trees, caverns, mountains and other rustic objects delineated in landscape style.’

VITRUVIUS,

PART ONE

Chapter I.

Across the Narrow Sea.

‘So now get up.’

Felled, dazed, silent, he has fallen; knocked full length on the cobbles of the yard. His head turns sideways; his eyes are turned towards the gate, as if someone might arrive to help him out. One blow, properly placed, could kill him now.

Blood from the gash on his head – which was his father's first effort – is trickling across his face. Add to this, his left eye is blinded; but if he squints sideways, with his right eye he can see that the stitching of his father's boot is unravelling. The twine has sprung clear of the leather, and a hard knot in it has caught his eyebrow and opened another cut.

‘So now get up!’ Walter is roaring down at him, working out where to kick him next. He lifts his head an inch or two, and moves forward, on his belly, trying to do it without exposing his hands, on which Walter enjoys stamping. ‘What are you, an eel?’ his parent asks. He trots backwards, gathers pace, and aims another kick.

It knocks the last breath out of him; he thinks it may be his last. His forehead returns to the ground; he lies waiting, for Walter to jump on him. The dog, Bella, is barking, shut away in an outhouse. I'll miss my dog, he thinks. The yard smells of beer and blood. Someone is shouting, down on the riverbank. Nothing hurts, or perhaps it's that everything hurts, because there is no separate pain that he can pick out. But the cold strikes him, just in one place: just through his cheekbone as it rests on the cobbles.

‘Look now, look now,’ Walter bellows. He hops on one foot, as if he's dancing. ‘Look what I've done. Burst my boot, kicking your head.’

Inch by inch. Inch by inch forward. Never mind if he calls you an eel or a worm or a snake. Head down, don't provoke him. His nose is clotted with blood and he has to open his mouth to breathe. His father's momentary distraction at the loss of his good boot allows him the leisure to vomit. ‘That's right,’ Walter yells. ‘Spew everywhere.’ Spew everywhere, on my good cobbles. ‘Come on, boy, get up. Let's see you get up. By the blood of creeping Christ, stand on your feet.’

Creeping Christ? he thinks. What does he mean? His head turns sideways, his hair rests in his own vomit, the dog barks, Walter roars, and bells peal out across the water. He feels a sensation of movement, as if the filthy ground has become the Thames. It gives and sways beneath him; he lets out his breath, one great final gasp. You've done it this time, a voice tells Walter. But he closes his ears, or God closes them for him. He is pulled downstream, on a deep black tide.