suffered temporary deafness.

Follow-up operations got under way at first light, but only limited kills were scored against the ZIPRA force, which had taken the precaution of splitting into small groups. Nevertheless the aim of driving ZIPRA from its base had been achieved.

Operation Dice

LANCASTER HOUSE TALKS HAD BEEN on the go for six weeks when Op Tepid wrapped up, and General Peter Walls had been called to London. Before his departure, the general listened to his COMOPS planning team’s ideas on how best to counter a ZIPRA invasion. We specifically argued against ambush and harassment tasks in Zambia because this would have limited effect in stemming any large-scale flow and would almost certainly lead to clashes with Zambian forces. Yet to await ZIPRA’s move and deal with each crossing-point on the Zambezi River, from Rhodesian soil, was obviously ridiculous. Not only would ZIPRA make its crossings at night to minimise interference from the Rhodesian Air Force, their powerful Soviet-supplied equipment would easily drive off any protection force during the critical stages of establishing a bridgehead on Rhodesian soil. Thereafter we would be forced to destroy some of our own bridges to hold up the enemy for Air Force attention in daylight.

Only the destruction of Zambia’s road bridges and culverts on all routes to our border made sense because this would prevent any large-scale movement. Our plans to cut the Great East Road from Lusaka to Malawi, the southern route from Lusaka to Chirundu, and the southwestern route from Lusaka to Livingstone were already complete.

General Walls needed no persuading. He realised only too well that Rhodesia’s David could only beat ZIPRA’s Goliath in this way. However, he was at pains to make us understand that the destruction of a Commonwealth member’s bridges would wreck any hope of the British Government showing any sympathy to the Muzorewa Government’s cause.

Whilst, from his understanding of the goings-on at Lancaster House, he doubted that any such empathy existed, we could not rock the boat just yet. General Walls said he would be in a better position to judge all issues once he got to London. In the meanwhile the SAS, Selous Scouts and RLI were to get on with the job of harassing ZIPRA movements. In consequence, Operation Dice started out with ambushing tasks to make access to Victoria Falls, Kariba and Chirundu difficult.

Masses of bridge demolition gear prepared for Op Manacle in Mozambique lay begging to be used when it was all too obvious to the frustrated SAS that only the destruction of bridges could meet our Zambian objectives. So, even though they had been told Op Dice only called for harassing work, SAS moved all the demolition gear to Kariba; just in case. It is just as well these explosives were immediately available. Without any forewarning during the night of 15 November, a signal from General Walls to COMOPS ordered the immediate implementation of our plans to destroy Zambian bridges.

Ian Smith had returned home from the Lancaster House talks on 11 November. On his arrival at the airport he told reporters that the British had manoeuvred the Muzorewa Government into accepting a bad agreement. He said there was now no alternative but to make the best of a bad deal. Without actually saying so, he implied (in my mind) that the British Conservative chairman of the conference, that poisonous snake Lord Carrington, had deliberately set the stage for a communist party take-over.

Thirteen times Rhodesians had celebrated Rhodesia’s Independence Day on 11 November but this was now a thing of the past—there was no longer anything to celebrate. This is why, even if General Wall’s ‘green light’ on the bridges seemed at odds with what Ian Smith had said four days earlier, we were delighted that Rhodesians were not going to take things lying down.

Whilst lawyers in London settled down to preparing written agreement for all parties’ signatures at some time in December, the SAS moved in on the bridges with RLI troops in support. We all knew they had to act fast before any political change in direction occurred. In four days, nine primary road bridges and one rail bridge were dumped. The SAS demolition teams had become so expert in their tasks that bridges were downed even before their Cheetah transport had reached their refuelling points back in Rhodesia. This not only resulted in the ground teams having an unnecessarily long wait for recovery, it put our COMOPS planners back to work revising methods, movement plans and time-scales for the destruction of Mozambican bridges in Op Manacle.

Eight of the Zambian bridges had been specifically selected to curb ZIPRA’s movements to the border. Another two across the Mubulashi River were not. Whereas we were disallowed from taking any action against railway bridges on the line from Lusaka to South Africa, the rail bridge on the Tanzam rail line and an adjacent road bridge over the Mubulashi River were taken out. This was to complement the downing of the Chambeshi bridges on the same line five weeks earlier and to deliberately pressurise the Zambia Government. If this over- stressed Kenneth Kaunda’s economy, it was nothing compared to what was planned next. The same SAS commander who had taken out the fuel refinery at Beira in Mozambique was about to launch a purely SAS raid to destroy Zambia’s large fuel refinery at Ndola. Simultaneous with this, Op Manacle was to go ahead on the Mozambican bridges. This was all very exciting stuff but it came to an abrupt end on 22 November when General Walls signalled COMOPS instructing that all external offensive operations were to cease forthwith. The war in Zambia and Mozambique was over. ZIPRA was out of the game, but General Walls instructed that internal operations against ZANLA were to be intensified until the expected ceasefire came into effect. He said this might occur before Christmas.

Chapter 10

Ceasefire

A TOTAL CEASEFIRE WAS TO come into immediate effect when all parties to the Lancaster House agreement signed the enacting document. As soon as this happened, the warring forces would cease hostilities and all BSA policemen were to revert to normal policing duties. The RSF were to return to barracks whilst ZIPRA and ZANLA forces were to move into sixteen (later increased to seventeen) assigned Assembly Points (APs) inside Rhodesia. The APs were to be under the control and protection of a Commonwealth Monitoring Force (CMF). Nothing was said of the Pfumo re Vanhu auxiliaries though, ultimately, they also remained in their bases.

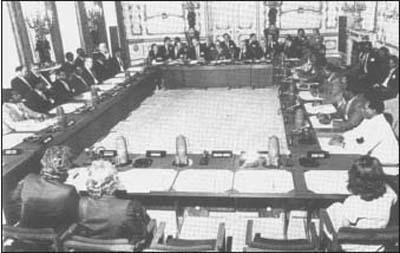

In addition to his main duties, the Commanding General of CMF was to head a Ceasefire Committee. This committee of eight, comprising two officers each from the British Army, the RSF, ZIPRA and ZANLA, was to facilitate inter-force co-operation and deal with any ceasefire violations that might occur.

When Lieutenant-General Walls returned to COMOPS from London, he called me to his office to tell me that, when the time came, I was to be his personal representative on the Ceasefire Committee. He said, “I refuse to sit with those bloody Brits and communists or give them any sense of equal rank with myself or any of the service commanders.” Because I held the rank group captain (Army equivalent colonel) he decided to lend weight of rank to RSF representation by recalling Major-General Bert Barnard from retirement, but only to attend committee meetings. All executive functions were to be handled by me. My lack of faith in Bert Barnard caused me some concern but, in the event, we got on fine.

In addition to Ceasefire Committee work, it would be my responsibility to act as the liaison officer between