country fair at Penhalonga in the east of the country. Late in the evening he was walking past an ox-wagon where an elderly man asked for his assistance. Dad was happy to comply by lifting a large blacksmith’s steel anvil from the ground onto the deck of the wagon. When he had done this he became aware of shouted congratulations and slaps on his back from a group of people he had not noticed until then. The elderly man also congratulated him and with great difficulty pushed the anvil off the wagon. He then invited Dad to lift the anvil back onto the wagon, this time for a handsome cash prize that none of many contenders had won. Dad tried but no amount of cheering and encouragement helped him even lift the anvil off the ground.

Mum moved with her parents to Southern Rhodesia in 1914 when she was four years of age. Her father was controller of the Rhodesian Railways storage sheds in Salisbury. He, together with Mum’s mother, ran a dairy and market garden on their large plot of land, one boundary of which bordered the bilharzia-ridden Makabusi River, south of the town.

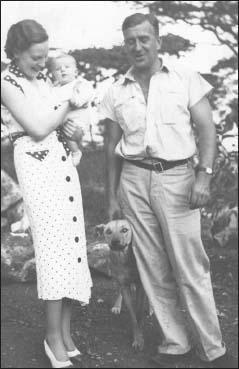

Mum attended Queen Elizabeth School in Salisbury where she acquired a taste for the high-society lifestyle of her friends, though this was not altogether to the liking of her middle-class father. She was christened Catherine Lillian Elizabeth but became known as Shirley because of her striking resemblance to a very beautiful and well-known, redheaded actress of the time. This nickname stuck to Mum for life; and she loved it. Her maiden name, Smith, on the other hand did not suit the image Mum desired. However, that all changed when she married Dad in early 1935.

Dad enjoyed the company of many male friends at the Salisbury City Club. It was from there that he went to register my birth following a lunchtime session to celebrate the birth of his first-born son. I guess he must have been fairly tipsy because he added an extra name to the ones he had agreed with my mother. To Peter John he added another family name, Hornby. In consequence, three of my names link me to family lines in sea, rail and air.

Two years after my birth my brother Paul Anthony (Tony) was born. Together we enjoyed a carefree childhood in the idyllic surroundings of the Rhodesian highveld. Our westward-facing home was set high on a ridge overlooking rolling farmlands, with the city of Salisbury and its famous

Both Mum and Dad worked. Dad had his own heavy-transport business, Pan-African Roadways, and Mum was personal secretary to the Honourable John Parker who headed up the Rhodesian Tobacco Association. So, with the exception of weekends, Tony and I were left from about 07:00 until 17:30 in the autocratic care of our African cook, Tickey. Tickey was the senior man over Phineas (washing and ironing), the housekeeper Jim (sweeping, polishing and making of beds), two gardeners and, during our younger years, someone to watch over our every move. Such a large Staff was commonplace in Southern Rhodesia in those days.

Tickey was a fabulous cook. Mum had taught him everything he knew but Tickey had a knack of improving on every dish he learned though the names of some gave him difficulty. For instance, he insisted on calling flapjacks “fleppity jeckets” because the common name of the African khaki weed, black jacks, had stuck in his mind as “bleckity jeckets”.

We had more black friends than white for many years and we really enjoyed their company. Together we hunted for field mice and cooked them over open fires, before consuming them with wild spinach and

Whenever possible, we limited our lunch intake to keep enough space so as to be able to join our African friends for

Only one hand was used to scoop up a lump of boiling hot

A gravel road running behind our spacious gardens served the line of homes built along the ridge on which we lived. Across this road lay various fruit and cereal farms and a big dairy farm. Beyond these lay a large forested area, full of colourful msasas and other lovely indigenous trees, through which ran two rivers. The larger of these was the Makabusi in which Tony and I were forbidden to swim because of bilharzia. Needless to say we swam with our mates whenever our wanderings brought us to the inviting pools bounded by granite surfaces and huge boulders. Being laid up in bed with bilharzia seemed a more attractive option than attending school. But try as we did, we failed to pick up the disease.

Ox wagons were still in use on the farms. This gave ample opportunity to try our hands at the three functions of leading the oxen, wielding the long whip and manning the hand-crank that applied brakes on downhill runs. The black men whose job it was to do these things were amazingly accommodating and never seemed annoyed by our presence.

When old enough to do so, Tony and I rode bicycles to David Livingstone School some four miles from home. I neither liked nor disliked school, but dreaded the attention of bullies who cornered me on many occasions. Dad told me one day that all bullies had one thing in common—they were very good at meting out punishment but cowardly when receiving it. Dad also told me that to accept one good hiding was better than receiving many lesser ones. I got the message and waited until the biggest and meanest of the bullies cornered me in an alley. I climbed into him with everything I had. He tried to break free but I pursued him with vigour until I realised that he was crying like a baby. Not only was I left alone from then on, I assumed the role of protector for other bullyboy victims. The attention I received from the girls was very confusing but strangely pleasing!

Tony and I were blessed with angelic singing voices and were often asked to sing for our beloved grandparents. We took this all for granted until one day we attended a wedding in the Salisbury Anglican Cathedral. After the service I got to talk with one of the choirboys. From him I learned that he had just been paid two shillings and sixpence, the going rate for singing at weddings. That added up to a lot of ice-creams; so Tony and I joined the Anglican Cathedral choir that very week. Dad was horrified when he learned his sons had joined the Anglican choir, though he never said why. Mum thought it a good idea.

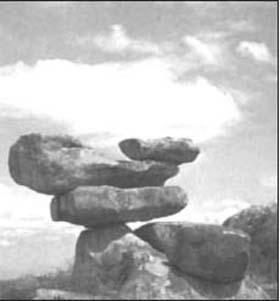

The organist and choirmaster were Mr Lillicrap and Mr Cowlard respectively—names that caused much amusement and some confusion for us. Nevertheless they were good at their work and taught us a great deal about singing. But going to church was a totally new experience for me because the nearest I had come to knowing about God arose from questions I had asked some years earlier when driving past one of Rhodesia’s famous balancing granite rock formations.

I asked Mum how the rocks had been placed in such precarious positions. When she told me that God had put them there I wanted to know how many Africans He had used to lift such massive rocks so high. I’m sure she gave me a sensible answer but it obviously went right over my head. Dad on the other hand planted information in my small mind, and it stuck. He told me that all of God’s tools are invisible. Some that we know and take for