In agony I was taken to SSQ where the doctor found that a section of bone had broken away from my heel and was being held apart from its rightful place by the ligament of the calf muscle. After treatment and with my leg in a plaster cast, I was ordered to bed for one week. Of all the members of my course, I was the least able to handle a full week off lectures. I feared that my misfortune might result in my failing ITS, even though Dave Thorne did his best to keep me abreast of what was being covered.

I had been laid up for a couple of days when Flight Sergeant Reg Lohan, the Officers’ Mess caterer, came to my room to say that a young lady had called and would be visiting me that afternoon. I went into a cold sweat believing Pat Woods had tracked me down again and I lay wondering how I was going to a handle this unhappy situation.

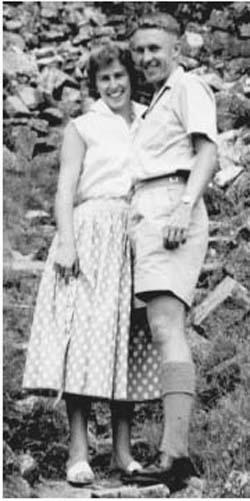

When Beryl Roe breezed into my room with Flight Sergeant Lohan, I was very relieved. She was an easy person to relate to and we discussed all sorts of things without any loss for words or subjects. Flight Sergeant Lohan sent us a tray with tea and cakes, which Beryl said was “so sweet of him.” Then the guys came back from classes and, without consulting me, they suggested to Beryl that we all go to the cinema that evening. Beryl accepted and persuaded me to go along. What an awful night! I was in agony with my foot on the floor, so Beryl insisted I lift it, plaster cast and all, onto her lap. We both agonised through the show and I was happy when the evening came to an end. Thereafter Beryl and I saw each other regularly, but only after she had shown me her passport to prove that she was nineteen years old and not twenty-six as I had thought.

On my twenty-first birthday we got engaged, before attending a dining-in at the Mess. Arranged by my course mates and Flight Sergeant Lohan to celebrate my coming-of-age it turned out to be an engagement celebration as well. So much for having nothing to do with women before completing pilot training!

Our Commanding Officer was Squadron Leader Doug Whyte—a superb individual who enjoyed the respect of everyone who ever met him.

He came to lecture us about the dangers of ‘crew-room bragging’, a real killer in any Air Force. With the aid of photographs taken of a fatal flying accident in the Thornhill Flying Training Area the previous year, the Squadron Leader pressed home his message to us. With our flying training about to commence he urged us all to exercise responsibility towards each other and never to brag or challenge others into unauthorised flying activities. The death of 9 SSU Officer Cadet Nahke had been the direct result of a crew-room bragger’s challenge to a tail- chase. In a steep turn, Nahke had probably entered the bragger’s slipstream and paid an awful price for his inexperience. The loss of a valuable aircraft and the unnecessary pain caused to a grieving family was simply too high a price to pay for sheer stupidity. The CO’s message was firmly embedded in all of us.

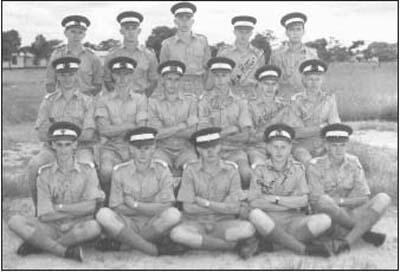

Two of our numbers were ‘scrubbed’ on the grounds of poor officer-potential and fourteen of us passed on to the BFS (Basic Flying School) phase. During the two weeks preceding BFS we had spent most of our free time in Provost cockpits learning the various routines and emergency drills that we were required to conduct blindfold. During this time we anxiously awaited news of who our personal flying instructors would be.

Basic Flying School

WE KNEW ALL OF THE instructors by sight and for weeks had heard the exciting sound of the Provosts on continuation training as instructors honed up their instructional skills.

One instructor had the reputation of being an absolute terroriser of student pilots, so we all feared being allocated to this strongly accented South African, Flight Lieutenant Mick McLaren. Murray Hofmeyr and I were the unlucky ones and everyone else breathed a sigh of relief.

The Percival Provost had replaced the Mk2 Harvards as the basic trainer and was quite different in many ways. The most important difference was that the Provost had side-by-side seating as opposed to the tandem arrangement of the Harvard. This permitted a Provost instructor to watch every movement his student made, which was not possible in the Harvard because the instructor’s instrument panel obstructed view of the front cockpit.

A single Leonides air-cooled, nine-cylinder radial engine powered the Provost’s three-bladed propeller. At sea level this engine developed 550 hp at 2,750 rpm Thornhill was 4,700 feet above sea level and the maximum power available at this level was reduced to about 450 hp, equating to the power developed by the Harvard’s Pratt and Whitney motor at the same height.

Whereas the Harvard had retractable main wheels, the Provost’s undercarriage was fixed, making an otherwise neat airframe look unsightly in flight. Apart from the cost of retractable wheels, the fixed undercarriage of the Provost prevented

The Harvard employed hydraulics to operate undercarriage, brakes and flaps. Toe pedals on the rudder controls activated the wheel brakes. However, there are penalties for using hydraulics. They incur high costs, high weight of hydraulic oil and the reservoir in which to house it, as well as hefty pipelines to deliver pressure to services with duplicated pipes to recover hydraulic fluid back to the oil reservoir.

The Provost designers opted for pneumatics to reduce cost and weight. By using compressed air there is only need for a single lightweight delivery line to each service point and a lightweight accumulator tank to store compressed air. But the advantages of using pneumatics presented difficulties to pilots insofar as control of brakes was concerned.

Wheel braking was effected by pulling on a lever, much like a vertically mounted bicycle brake lever affixed to the fighter-styled hand grip on the flight control column. The position of the rudder bar determined how the wheel brakes would respond. If, say, a little left rudder was applied, braking was mainly on the left wheel and less on the right. The differential increased progressively until full left rudder gave maximum braking on the left wheel only. With rudder bar set central, both wheels responded equally to the amount of air pressure applied by means of the brake lever.

Attainment of proficiency in handling brakes was of such importance that, before flying started, the instructors spent time with their students simply taxiing in and out of dispersals. The ground Staff revelled in watching brand-new students trying to control their machines, even drawing men off the line from other squadrons.

Every aircraft of any type exhibits different characteristics to others of its own kind, which is why many Air Forces allocate an aircraft to an individual pilot or crew. No brake lever on Provosts, whether student’s or instructor’s side, felt or acted the same. They varied from a spongy, smooth feel, which was best, to those sticky ones that would not yield to normal pressure and then snap to maximum braking with the slightest hint of added pressure. The instructors knew which aircraft had sticky brake levers and it was these that they preferred for initial taxi training. Once a student was proficient on the ground, the flying began.

Firing a cordite starter cartridge started the Provost engine. Raising a handle set on the floor between the seats did this. At its end was a primer button that injected fuel into the engine during the three revolutions given by the cartridge starter motor. Learning engine start-up, particularly when the engine was hot, was quite a business largely because of a tendency to over-prime and flood the cylinders. ‘Duck shooting’ was the term used by technicians when pilots fired more than two cartridges. Years later electric starter motors were introduced, making matters much easier.