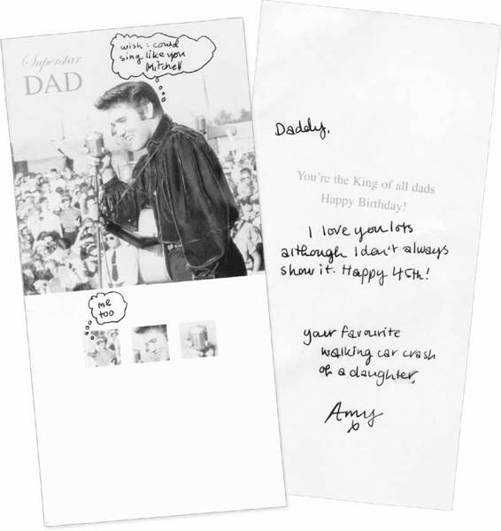

I’ve been told I was gifted with a lovely voice and I guess my dad’s to blame for that. Although unlike my dad, and his background and ancestors, I want to do something with the talents I’ve been ‘blessed’ with. My dad is content to sing loudly in his office and sell windows.

My mother, however, is a chemist. She is quiet, reserved.

I would say that my school life and school reports are filled with ‘could do betters’ and ‘does not work to her full potential’.

I want to go somewhere where I am stretched right to my limits and perhaps even beyond.

To sing in lessons without being told to shut up (provided they are singing lessons).

But mostly I have this dream to be very famous. To work on stage. It’s a lifelong ambition.

I want people to hear my voice and just forget their troubles for five minutes.

I want to be remembered for being an actress, a singer, for sell-out concerts and sell-out West End and Broadway shows.

I think it was to the school’s relief when Amy left Ashmole. She started at the Sylvia Young Theatre School when she was about twelve and a half and stayed there for three years – but what a three years it was. It was still school, which meant she was always being told off, but I think they put up with her because they recognized that she had a special talent. Sylvia Young herself said that Amy had a ‘wild spirit and was amazingly clever’. But there were regular ‘incidents’ – for example, Amy’s nose-ring. Jewellery wasn’t allowed, a rule Amy disregarded. She would be told to take the nose-ring out, which she would do, and ten minutes later it was back in.

The school accepted that Amy was her own person and gave her a degree of leeway. Occasionally they turned a blind eye when she broke the rules. But there were times when she took it too far, especially with the jewellery. She was sent home one day when she’d turned up wearing earrings, her nose-ring, bracelets and a belly-button piercing. To me, though, Amy wasn’t being rebellious, which she certainly could be; this was her expressing herself.

And punctuality was a problem. Amy was late most days. She would get the bus to school, fall asleep, go three miles past her stop, then have to catch another back. So, although this was where Amy wanted to be, it wasn’t a bed of roses for anyone.

Amy’s main problem at Sylvia Young’s was that, as well being taught stagecraft, which included ballet, tap, other dance, acting and singing, she had to put up with the academic side or, as Amy referred to it, ‘all the boring stuff’. About half of the time was allocated to ‘normal’ subjects and she just wasn’t interested. She would fall asleep in lessons, doodle, talk and generally make a nuisance of herself.

Amy really got into tap-dancing. She was pretty good at it when she started at the school but now she was learning more advanced techniques. When we were at my mother’s flat for dinner on Friday nights, Amy loved to tap-dance on the kitchen floor because it gave a really good clicking sound. The clicks it gave were great. I told her she was as good a dancer as Ginger Rogers, but my mother wouldn’t have that: she said Amy was better.

Amy would put her tap shoes on and say, ‘Nan, can I tap-dance?’

‘Go downstairs and ask Mrs Cohen if it’s all right,’ my mum would reply, ‘because you know what she’s like. She’ll only complain to me about the noise.’

So Amy would go and ask Mrs Cohen if it was all right and Mrs Cohen would say, ‘Of course it’s all right, darling. You go and dance as much as you like.’ And then the next day Mrs Cohen would complain to my mum about the noise.

After dinner on a Friday night, we’d play games. Trivial Pursuit and Pictionary were two of our favourites. Amy and I played together, my mum and Melody made up the second team, with Jane and Alex as the third. They were the ‘quiet’ ones, thoughtful and studious, my mum and Melody were the ‘loud’ pair, with a lot of screaming and shouting, while Amy and I were the ‘cheats’. We’d try to win no matter what.

When she wasn’t playing games or tap-dancing, Amy would borrow my mum’s scarves and tops. She had a way of making them seem not like her nan’s things but stylish, tying shirts across her middle and that sort of thing. She also started wearing a bit of makeup – never too much, always understated. She had a beautiful complexion so she didn’t use foundation, but I’d spot she was wearing eyeliner and lipstick – ‘Yeah, Dad, but don’t tell Mum.’

But while my mum indulged Amy’s experiments with makeup and clothes, she hated Amy’s piercings. Later on when Amy began getting tattoos, she’d have a go at her about all of it. Amy’s ‘Cynthia’ tattoo came after my mum had passed away – she would have loathed it.

Along with other pupils from Sylvia Young’s, Amy started getting paid work around the time she became a teenager. She appeared in a sketch on BBC2’s series

Eventually Janis and I were called in to see the head teacher of the school’s academic side, who told us he was very disappointed with Amy’s attitude to her work. He said that he constantly had to pressure her to buckle down and get some work done. He accepted that she was bored and they even tried moving her up a year to challenge her more, but she became more distracted than ever.

The real blow came when the academic head teacher phoned Janis, behind Sylvia Young’s back, and told her that if Amy stayed at the school she was likely to fail her GCSEs. When Sylvia heard about this she was very upset and the head teacher left shortly afterwards.

Contrary to what some people have said, including Amy, Amy was not expelled from Sylvia Young’s. In fact, Janis and I decided to remove her as we believed that she had a better chance with her exams at a ‘normal’ school. If you’re told that your daughter is going to fail her GCSEs, then you have to send her somewhere else. Amy didn’t want to leave Sylvia Young’s and cried when we told her that we were taking her away. Sylvia was also upset and tried to persuade us to change our minds, but we believed we were doing the right thing. She stayed in touch with Amy after she’d left, which surprised Amy, given all the rows they’d had over school rules. (Our relationship with Sylvia and her school continues to this day. From September 2012, Amy’s Foundation will be awarding the Amy Winehouse Scholarship, whereby one student will be sponsored for their entire five years at the school.)

Amy had to finish studying for her GCSEs somewhere, though, and the next school to get the Amy treatment was the all-girls Mount School in Mill Hill, north-west London. The Mount was a very nice, ‘proper’ school where the students were decked out in beautiful brown school uniforms – a huge change from leg warmers and nose- rings. Music was strong there and, in Amy’s words, kept her going. The music teacher took a particular interest in her talent and helped her settle in. I use that term loosely. She was still wearing her jewellery, still turning up late and constantly rowing with teachers about her piercings, which she delighted in showing to everybody. When I remember where some of those piercings were, I’m not surprised the teachers got upset. But, one way or another, Amy got five GCSEs before she left the Mount and yet another set of breathless teachers behind her.

There was no question of her staying on for A levels. She had had enough of formal education and begged us to send her to another performing-arts school. Once Amy had made up her mind, that was it: there was no chance of persuading her otherwise.

When Amy was sixteen she went to the BRIT School in Croydon, south London, to study musical theatre. It was an awful journey to get there – from the north of London right down to the south, which took her at least three hours every day – but she stuck at it. She made lots of friends and impressed the teachers with her talent and personality. She also did better academically: one teacher told her she was ‘a naturally expressive writer’. At the BRIT School Amy was allowed to express herself. She was there for less than a year but her time was well spent and the school made a big impact on her, as did she on it and its students. In 2008, despite the personal problems she was having, she went back to do a concert for the school by way of a thank-you.