small return for his kindness. He was delighted, and I know that it is now reverently wrapped in tissue-paper in the box beneath his bed, not too far from where it ought to be, buried on the great shining dunes, feeling only the shifting sand as the penguins thump solidly overhead.

Chapter Three

THE GOLDEN SWARM

They appeared to be of a loving disposition, and lay huddled together, fast asleep, like so many pigs.

The penguin colony near Huichi's

Peninsula Valdes lies on the coast of the province of Chubut. It is a mass of land rather like an axe-head, some eighty miles long by thirty broad. The peninsula is almost an island, being connected to the mainland by such a narrow neck of land that, as you drive along it, you can see the sea on both sides of the road. Entering the peninsula was like coming into a new land. For days we had driven through the monotonous and monochrome Patagonian landscape, flat as a billiard-table and apparently devoid of life. Now we reached the fine neck of land on the other side of which was the peninsula, and suddenly the landscape changed. Instead of the small, spiky bushes stretching purply to the horizon, we drove into a buttercup-yellow landscape, for the bushes were larger, greener and each decked with a mass of tiny blooms. The countryside was no longer flat but gently undulating, stretching away to the horizon like a yellow sea, shimmering in the sun.

Not only had the landscape changed in colouring and mood but had suddenly become alive. We were driving down the red earth road, liberally sprinkled with back-breaking potholes,* when suddenly I caught a flash of movement in the undergrowth at the side of the road. Tearing my eyes away from the potholes I glanced to the right, and immediately trod on the brakes so fiercely that there were frenzied protests from all the female members of the party. But I simply pointed, and they became silent.

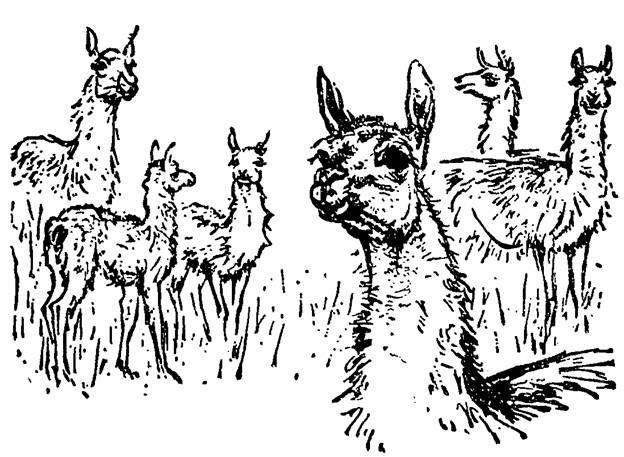

To one side of the road, standing knee-deep in the yellow bushes, stood a herd of six guanacos, watching us with an air of intelligent interest. Now guanacos are wild relatives of the llama, and I had been expecting to see something that was the same rather stocky shape as the llama, with a dirty brown coat. At least, I remembered that the one I had seen in a Zoo many years before looked like that. But either my memory had played me false* or else it had been a singularly depressed specimen I had seen. It had certainly left me totally unprepared for the magnificent sight these wild guanacos made.

What I took to be the male of the herd* was standing a little in front of the others and about thirty feet away from us. He had long, slender racehorse legs, a streamlined body, and a long slender graceful neck reminiscent of a giraffe's. His face was much longer and more slender than a lama's, but wearing the same supercilious expression. His eyes were dark and enormous. His small neat ears twitched to and fro as he put up his chin and examined us as if through a pair of imaginary lorgnettes.*

Behind him, in a tight and timid bunch, stood his three wives and two babies, each about the size of a terrier,* and they had such a look of wide-eyed innocence that it evoked strange anthropomorphic* gurgles and gasps from the feminine members of the expedition. Instead of the dingy brown I had expected these animals almost glowed. The neck and legs were a bright yellowish colour, the colour of sunshine on sand, while their bodies were covered with a thick fleece of the richest biscuit brown.* Thinking that we might not get such a chance again I determined to get out of the Land-Rover and film them. Grabbing the camera I opened the door very slowly and gently. The male guanaco put both ears forward and examined my maneuver with manifest suspicion. Slowly I closed the door of the Land-Rover and then started to lift the camera. But this was enough. They did not mind my getting out of the vehicle, but when I started to lift a black object – looking suspiciously like a gun – to my shoulder this was more than they could stand. The male uttered a snort, wheeled about, and galloped off, herding his females and babies in front of him. The babies were inclined to think this was rather a lark,* and started gambolling in circles, until their father called them to order with a few well-directed kicks.

When they got some little distance away they slowed down from their first wild gallop into a sedate, stiff-legged canter. They looked, with their russet and yellow coats, like some strange ginger-bread animals, mounted on rockers,* tipping and tilting their way through the golden scrub.

As we drove on across the peninsula we saw many more groups of guanacos, generally in bunches of three or four, but once we saw a group of them standing on a hill, outlined against a blue sky, and I counted eight individuals in the herd. I noticed that the herds were commoner towards the centre of the peninsula, and became considerably less common as you drove towards the coast. But wherever you saw them they were cautious and nervous beasts, ready to canter off at the faintest hint of anything unusual, for they are persecuted by the local sheep-farmers, and have learnt from bitter experience that discretion is the better part of valour.*

By the late afternoon we were nearing Punta del Norte on the east coast of the peninsula, and the road had faded away into a pair of faint wheel-tracks that wended their way through the scrub in a looping and vague manner that made me doubt whether they actually led anywhere. But, just when I was beginning to think that we had taken the wrong track, I saw up ahead a small white

They were fascinated by the thought that I should have come all the way from England just to catch and film

We found it without too much difficulty, and it was as good as the peons had promised, a small, level plain covered with coarse grass and occasional clumps of small, twisted dead bushes. On three sides it was protected by a curving rim of low hills, covered in yellow bushes, and on the third side a high wall of shingle lay between it and the sea. This offered us some cover, but even so there was a strong and persistent wind blowing from the sea, and now that it was evening it became very cold. It was decided that the three female members of the party would sleep inside the Land-Rover, while I slept under it. Then we dug a hole, collected dry brushwood and built a fire to make tea. One had to be very careful about the fire, for we were surrounded by acres and acres of tinder-dry undergrowth, and the strong wind would, if you were not careful, lift your whole fire up into the air and dump it down among the bushes. I dreaded to think what the ensuing conflagration would be like.

The sun set in a nest of pink, scarlet and black clouds, and there was a brief green twilight. Then it darkened, and a huge yellow moon appeared and gazed down at us as we crouched around the fire, huddled in all the clothes we could put on, for the wind was now bitter. Presently the Land-Rover party crept inside the vehicle, with much grunting and argument as to whose feet should go where, and I collected my three blankets, put earth on the fire, and then fashioned myself a bed under the back axle of the Land-Rover. In spite of the fact that I was wearing three pullovers, two pairs of trousers, a duffel-coat and a woolly hat, and had three blankets wrapped round me, I was still cold, and as I shivered my way into a half-sleep,* I made a mental note that on the morrow I would reorganise our sleeping arrangements.

I awoke in that dimly-lit silence just before dawn, when even the sound of the sea seems to have hushed. The wind had switched direction in the night, and the wheels of the Land-Rover now offered no protection at all. The hills around were black against the blue-green of the dawn sky, and there was no sound except the hiss of the wind and the faint snore of the surf. I lay there, shuddering, in my cocoon of clothes and blankets, and debated whether or not I should get up and light the fire and make some tea. Cold though I was under my clothes, it was still a few degrees warmer than wandering about collecting brushwood, and so I decided to stay where I was. I was just trying to insinuate my hand into my duffel-coat pocket for my cigarettes, without letting a howling wind into my cocoon of semi-warmth,* when I realized that we had a visitor.

Suddenly a guanaco stood before me, as if conjured out of nothing. He stood some twenty feet away, quite still, surveyed me with a look of surprise and displeasure, his neat ears twitching back and forth. He turned his head, sniffing the breeze, and I could see his profile against the sky. He wore the supercilious expression of his race, the faint aristocratic sneer, as if he knew that I had slept in my clothes for the past three nights. He lifted one forefoot daintily, and peered down at me closely. Whether, at that moment, the breeze carried my scent to him I don't know, but he suddenly stiffened and, after a pause for meditation, he belched.

It was not an accidental gurk, the minute breach of good manners that we are all liable to at times. This was a premeditated, rich and prolonged belch, with all the fervour of the Orient in it. He paused for a moment, glaring at me, to make sure that his comment on my worth had made me feel properly humble, and then he